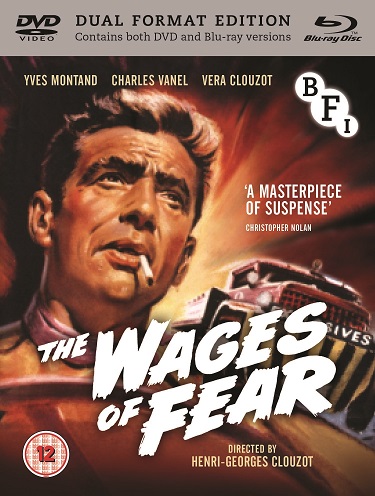

DVD/Blu-ray: The Wages of Fear

Arguably the greatest action film ever. Watch from behind the sofa...

The opening shot sets the tone for what follows: a pair of duelling cockroaches attached to a string, tormented by a bored child. In 1953’s The Wages of Fear, we quickly sense that Henri-Georges Clouzot’s characters are similarly powerless. His multi-national misfits, marooned in an unnamed South American town, are effectively prisoners, scrabbling around for the money with which to escape a place which is “like a prison: easy to get in, impossible to get out”. The film’s exposition is overlong, but creates a sense of oppressive dread.

As with Hitchcock’s The Birds, the leisurely first act means that the ensuing shocks hit home that much harder, the set-up (taken from a novel by George Arnaud) being that a serious fire at an American-owned oil well can only be extinguished with the aid of two truckloads of volatile nitro-glycerin. The Americans realise that they’ve a ready supply of willing recruits to drive them, the depot manager stating bluntly that “these bums don’t have any union – they’ll work for peanuts.” Drive too quickly and the consignment will detonate, and the four bums chosen have just a 50/50 chance of success.

Yves Montand’s strutting Mario and Charles Varnel’s sly hard man Jo drive the first truck, followed by Peter van Eyck and Folco Lulli as Bimba and Luigi. What ensues is unbearably tense: who’d have imagined that a pair of slow-moving lorries could instil so much terror? Predictably, this isn’t an easy ride: bumpy roads, rock falls, and a pool filled with crude oil all play significant parts. The famous sequence where the trucks reverse onto a shaky wooden platform remains uniquely terrifying.

Yves Montand’s strutting Mario and Charles Varnel’s sly hard man Jo drive the first truck, followed by Peter van Eyck and Folco Lulli as Bimba and Luigi. What ensues is unbearably tense: who’d have imagined that a pair of slow-moving lorries could instil so much terror? Predictably, this isn’t an easy ride: bumpy roads, rock falls, and a pool filled with crude oil all play significant parts. The famous sequence where the trucks reverse onto a shaky wooden platform remains uniquely terrifying.

As the tension rises, the pressure tells on the protagonists. Mario’s apparent bravery tips over into brutal thuggery and the cocky Jo turns into a snivelling wretch, though one undeserving of the fate which later befalls him. Clouzot’s bleak vision still looks and sounds unerringly modern: Armand Thiraud’s gleaming monochrome cinematography and Georges Auric’s minimal score haven’t dated at all. And the film’s nihilistic close remains a shocker.

This BFI reissue gives us The Wages of Fear uncut in a new 4K restoration, and comes with generous bonus features. Adrian Martin’s commentary is insightful, and there’s a long audio-only interview in English with Yves Montand: recorded in 1989, the star discussing his distinguished career. The best extras include an account of Clouzot’s chequered career and a revealing interview recorded in 2005 with Clouzot’s hard-working assistant director, Michel Romanoff. We learn that the film was actually shot in the Camargue region of south-west France, and that the huge boulder which blocks the road at one point took the crew several weeks to actually push into position. There’s an excellent booklet too, including contemporary responses by director Karel Reisz and critic Penelope Houston.

Overleaf: watch the 1953 trailer for The Wages of Fear

All of which makes the arrival of an outsider an unwelcome disruption. Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu) has come from Romania to help for a few weeks with the lambing – he was the only applicant for the job – and Johnny’s hostility is immediate as he taunts him as a “gyppo”. They are going up to the higher pastures for the lambing, to sleep in a ruined hut and subsist, it seems, entirely on pot noodles. Then up there, when least expected, fate stumbles in: in this stark isolation the hostility between the two men turns into something else, Johnny’s anger giving way to tussling, and that into physical contact. At first they fight in the mud, rutting like animals, before a deeper contact slowly grows between them. They may still guy one another, but their words – “freak”, “faggot” – are no longer insults, rather signifiers of an new, joshing intimacy.

All of which makes the arrival of an outsider an unwelcome disruption. Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu) has come from Romania to help for a few weeks with the lambing – he was the only applicant for the job – and Johnny’s hostility is immediate as he taunts him as a “gyppo”. They are going up to the higher pastures for the lambing, to sleep in a ruined hut and subsist, it seems, entirely on pot noodles. Then up there, when least expected, fate stumbles in: in this stark isolation the hostility between the two men turns into something else, Johnny’s anger giving way to tussling, and that into physical contact. At first they fight in the mud, rutting like animals, before a deeper contact slowly grows between them. They may still guy one another, but their words – “freak”, “faggot” – are no longer insults, rather signifiers of an new, joshing intimacy. All of this is conveyed with such tenderness, expressed far more through images than in the very spare words of Lee’s script (his minimal use of music, principally tracks by A Winged Victory for the Sullen, is also all the more powerful for its sparseness). The sense of change feels somehow primal: simply, the two men come down from the hills different people. Johnny has started to feel things that he never knew he could, while for Gheorghe – everything we hear about his back story and homeland is unremittingly pessimistic, “My country is dead” – the possibility of settling, rather than wandering may have become real.

All of this is conveyed with such tenderness, expressed far more through images than in the very spare words of Lee’s script (his minimal use of music, principally tracks by A Winged Victory for the Sullen, is also all the more powerful for its sparseness). The sense of change feels somehow primal: simply, the two men come down from the hills different people. Johnny has started to feel things that he never knew he could, while for Gheorghe – everything we hear about his back story and homeland is unremittingly pessimistic, “My country is dead” – the possibility of settling, rather than wandering may have become real.

The other guests may be waiting for the end, but that doesn’t stop them enjoying more everyday routines, among which is an unlikely evening television show titled Flying Saucer. Daya establishes a particular bond with Vimla (Navnindra Behl), a widow who had accompanied her late husband here years ago and has stayed on ever since. There’s much affectionate humour in their interaction: there’s a moment when Daya appears to be on his deathbed, surrounded by mourners and musicians, with Vimla trying to catch his last words. “What did he say?” a musician asks. “That you sing in tune, please,” she replies.

The other guests may be waiting for the end, but that doesn’t stop them enjoying more everyday routines, among which is an unlikely evening television show titled Flying Saucer. Daya establishes a particular bond with Vimla (Navnindra Behl), a widow who had accompanied her late husband here years ago and has stayed on ever since. There’s much affectionate humour in their interaction: there’s a moment when Daya appears to be on his deathbed, surrounded by mourners and musicians, with Vimla trying to catch his last words. “What did he say?” a musician asks. “That you sing in tune, please,” she replies.