In Alan Hollinghurst’s first novel, The Swimming Pool Library (1988), set during the summer of 1983, the young gay narrator, William Beckwith, lives in Holland Park. That same year and location furnish the setting of the first part of Hollinghurst’s third novel, his masterpiece, The Line of Beauty (2004), in which the young gay hero, Nick Guest, becomes a lodger – a guest – in the house of a recently elected Tory MP, Gerald Fedden, whose son Toby he’d fancied at Oxford.

Nick loses his virginity with a young black man called Leo in the bushes of a communal garden behind the Feddens’ house, presumably Ladbroke Square. Toby’s counterpart in Our Evenings is a Tory MP, Giles Hadlow, a Boris Johnson-style brute whose parents Mark and Cara invite the young gay narrator, Dave Win, to supper at their house in Holland Park.

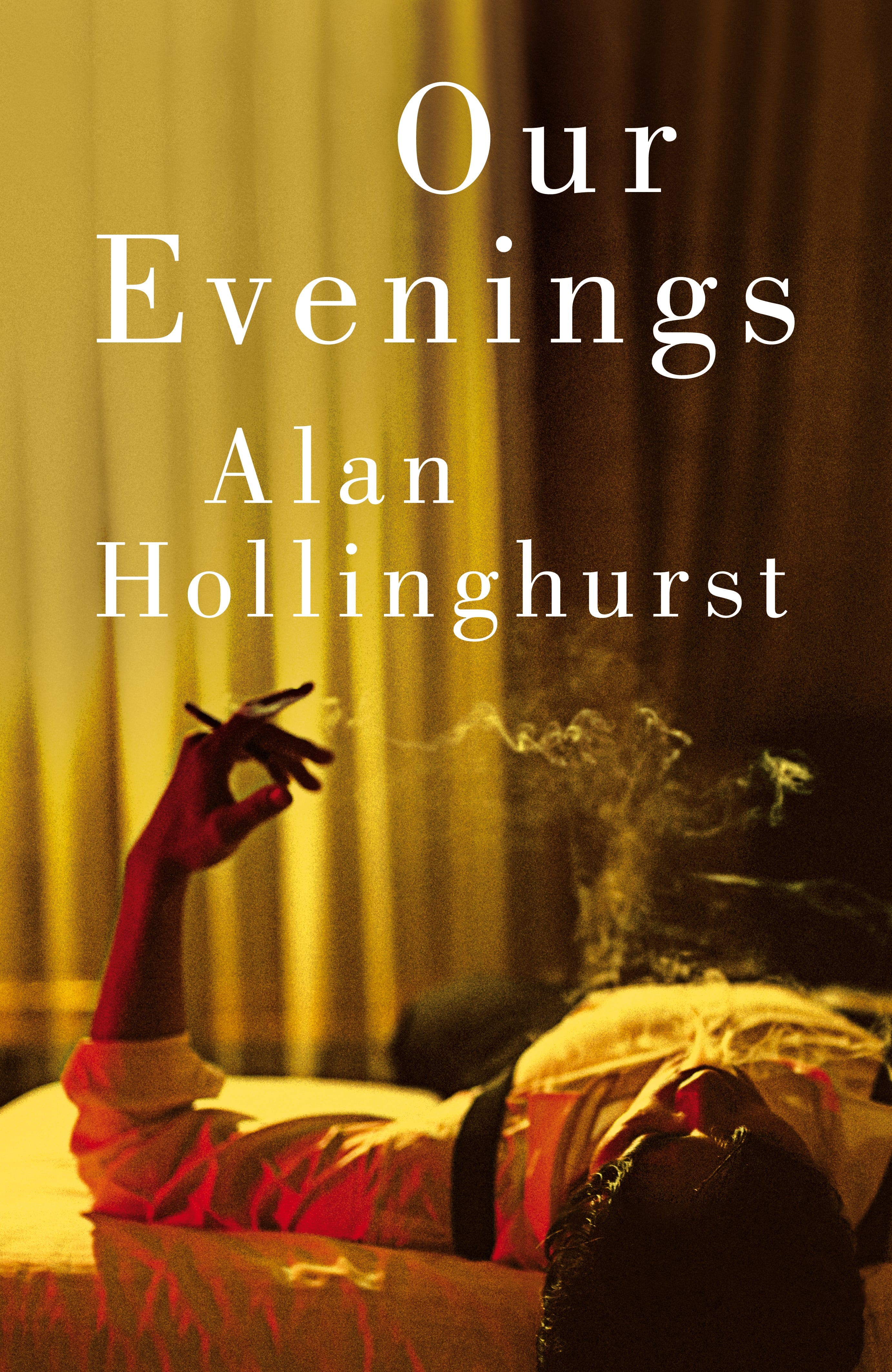

It’s not difficult to see a pattern here. Yet the new book is also a kind of departure. A sequence of lushly detailed episodes across six decades, from the 1960s to Brexit and the pandemic, Our Evenings is an atmospheric novel about all the usual Hollinghurstian concerns: sex, power and class. Often wickedly funny, it is full of the typical set pieces you expect from one of his novels – an opulent London drinks party, say, or a country-house weekend – and the book’s elegiac tone is sustained by the characteristic elegance of Hollinghurst’s prose.

As with The Swimming Pool Library and The Line of Beauty, the main character becomes infatuated with a black lover, in this case, an actor called Hector, who lives in “a tall council block near Latimer Road”, presumably Grenfell Tower overlooking Holland Park. Yet, in the latest novel, Hollinghurst manages to kick this habit of objectification because his narrator isn’t just a fellow actor, he is also a person of colour himself.

Dave is the bi-racial son of a white single mother, a lesbian dressmaker called Avril, who, in the late 1940s, while working as a secretary for the British colonial administration in Rangoon, had a brief affair with a Burmese man. As a boy growing up in a small Berkshire town, Dave wins a scholarship endowed by Mark and Cara Hadlow to a prestigious public school where he encounters the unsubtle racism of the British upper classes for the first time.

Dave is the bi-racial son of a white single mother, a lesbian dressmaker called Avril, who, in the late 1940s, while working as a secretary for the British colonial administration in Rangoon, had a brief affair with a Burmese man. As a boy growing up in a small Berkshire town, Dave wins a scholarship endowed by Mark and Cara Hadlow to a prestigious public school where he encounters the unsubtle racism of the British upper classes for the first time.

His foreign-looking appearance means that Dave holds an uncertain position at Bampton School where he is sadistically bullied by the Hadlow’s spoilt son Giles, and at Oxford where his infatuation with the university’s gilded youth produces a wonderful mixture of breathless yearning desire as well as comical details associated with real sex.

Hollinghurst writes movingly about Dave’s experience of racism and sex but he’s also very good at noticing the often unconsidered cruelty of love and friendship, and much of the pleasure of reading Our Evenings derives from the application of his famously high style to the low morals of the governing class. In a brief prelude, we learn that Giles who rises through the ranks of the Conservative Party, again during the 1980s, was one of the architects of the Brexit referendum and may now be destined for Downing Street because he is “a cheat and a bully, and very good at being both, like so many Tory politicians.”

The book also contains a set piece as powerful as anything that Hollinghurst has ever written when Dave, having published an actorish memoir, is invited to speak at “one of those smaller book festivals which flourish on the snob appeal of spending a weekend in the home of a duke”. In a moment of high comedy, Dave runs into its star attraction, Giles, who is puffing a Festschrift for his sixtieth birthday, with “a foreword by Baroness Margaret Thatcher OM, a fact so absurd that I laughed out loud”, and dispensing jovial snubs to his rapt audience.

Hollinghurst’s narrator is poignantly attuned to the gulf in significance between the rapture and his own understanding of Giles’s character: “I had always to remember that, for others, millions of them, Giles had the heft of a senior politician, a man who could be looked to change things, with all the glamour and gravity of government about him, his mastery of arts unknown to his followers, who trusted him to get things done. And maybe it was a limitation in me to see him only, or in essence, as an adolescent sadist, a spoilt hand-biting brat, who could never, surely, be taken seriously by anyone.”

Towards the end of Our Evenings we learn that Dave is now writing his memoirs in a Proustian attempt to capture the mystery of a recollected past: “I remember places, and experiences, very clearly, but they’re stills, you know, rather than clips. Or gifs perhaps, sometimes – a head turns, a hand comes down, but you never see what comes next, it just does it again.” In fact, this somewhat halting narrative effect is one of Hollinghurst’s trademarks so it doesn't take a literary genius to realise that the book Dave is describing is actually the one we’ve been reading.

Our Evenings is rather long and drawn out. At times the story lacks momentum because the pace of the storytelling is so deliberately glacial. Nevertheless it isn’t just a book with politicians in the background, it’s also a political novel in a way that The Line of Beauty isn’t, and if the foreground sometimes lingers too much on the mundane, perhaps that mundaneness is part of the novel’s complexity, a device to capture the paralysis of Britain over the past decade: “In a few weeks history went backwards by a century.”

- Our Evenings by Alan Hollinghurst (Picador, £22)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment