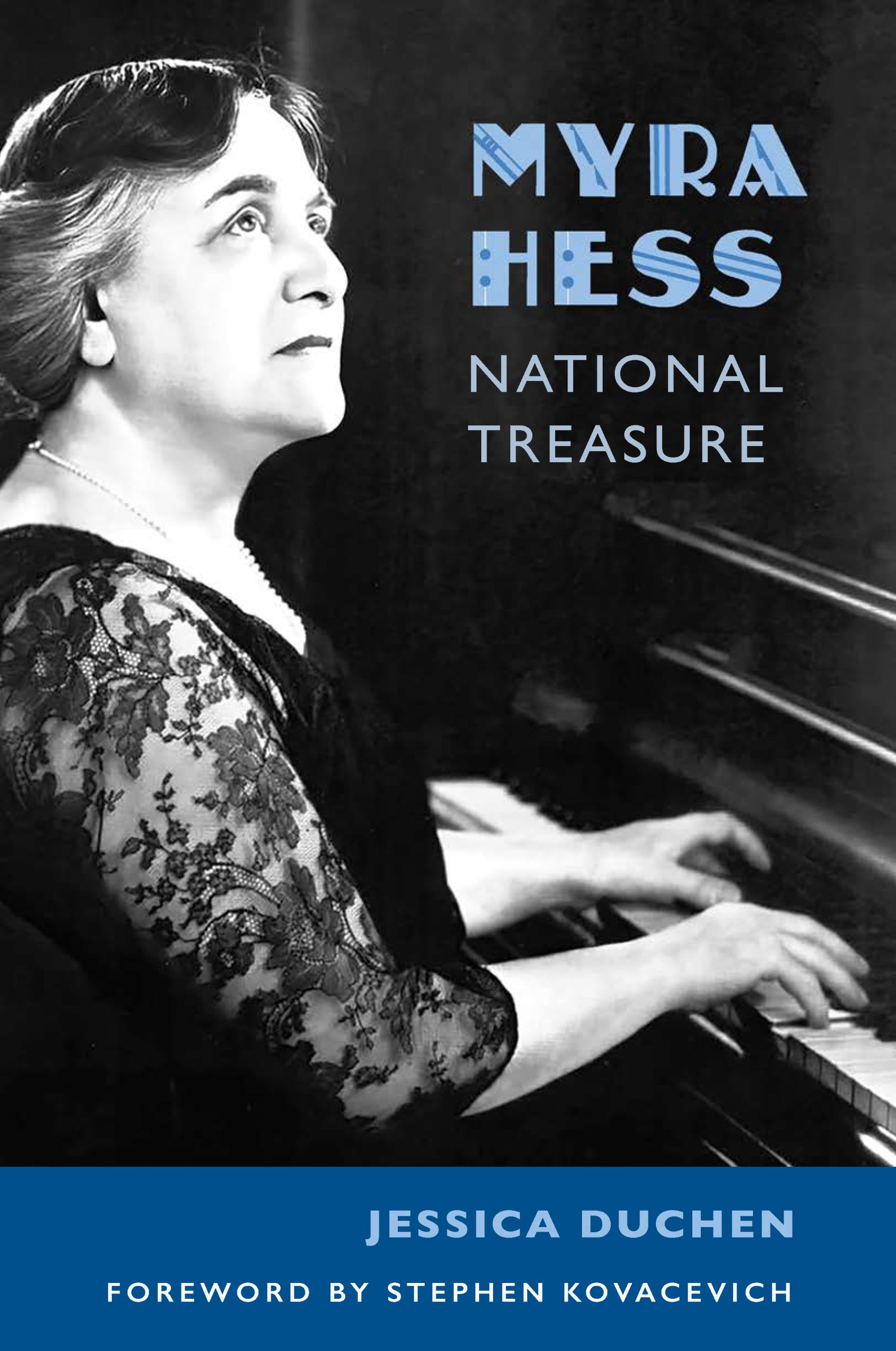

Myra Hess was one of the most important figures in British cultural life in the mid-20th century: the pre-eminent pianist of her generation and accorded “national treasure” status as a result of the wartime lunchtime concert series at London’s National Gallery, which she singlehandedly masterminded through 1,698 concerts between 1939 and 1946.

This new biography, the first for nearly 50 years, is meticulously researched and richly illustrated: Jessica Duchen brings to her task not just the biographer’s curious eye but a music critic’s ear and discernment.

Hess had to battle prejudices throughout her life, from her Jewish background, her Germanic name and – above all – her being a woman. From the earliest reviews there are snide and condescending remarks about her sex, even from the ostensibly sympathetic (“Miss Hess is essentially a woman’s pianist”; “every fibre in her comely and well poised body is musical”; and so on). The fact she rose from a difficult family – her father was a habitual adulterer and eventual bankrupt – to become a Dame and leave the equivalent of £1 million in today’s money in her will, speaks to her strength of character and singlemindedness.

She would – and did – sacrifice everything for her career. She never had an intimate romantic relationship (Duchen makes some hints about Arnold Bax) and spent much of her time on the road, not just around the UK, but also in the Netherlands and, above all, in the USA. Here she travelled almost annually for over 30 years (apart from during WWII), often spending four months at a time traversing coast-to-coast by train, with her piano in tow, giving concerts from New York to San Francisco and everywhere in between. She was rewarded with adulation, professional glories (the list of conductors she worked with is a Who’s Who) and creature comforts unknown in austerity Britain.

She would – and did – sacrifice everything for her career. She never had an intimate romantic relationship (Duchen makes some hints about Arnold Bax) and spent much of her time on the road, not just around the UK, but also in the Netherlands and, above all, in the USA. Here she travelled almost annually for over 30 years (apart from during WWII), often spending four months at a time traversing coast-to-coast by train, with her piano in tow, giving concerts from New York to San Francisco and everywhere in between. She was rewarded with adulation, professional glories (the list of conductors she worked with is a Who’s Who) and creature comforts unknown in austerity Britain.

But it was in Britain that her lasting legacy was forged: in the early days of WWII she had the idea to stage daily concerts in the National Gallery, whose artworks had all been dispersed, and which provided a central – if not especially acoustically-suited – venue. She took on not just the administration of the concerts, but performed more times than anyone else. It was an extraordinary achievement and deserved the recognition she received, including from the then-Queen, who attended several times. The ending of the concerts after the war, when the gallery returned to its original purpose, was a huge disappointment to her, although it was surely right the concerts should come to an end. After this dramatic peak, the story tails away a little into a slightly repetitive catalogue of her American tours, although these are brought to life by the witty diaries she kept en route. The details of the end of her career in her 70s – essentially, no one was brave enough to tell her she had to stop – make painful reading.

As a player Hess focused on mainstream Germanic repertoire – Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, Bach – and had little truck with contemporary music. Duchen writes perceptively about her playing, which has survived in some recordings – although not many, as Hess didn’t really like the process. Her most famous piece, a transcription she made in 1926 of Bach’s chorale movement Jesu, joy of man’s desiring, went with her everywhere (and made her a lot of money). There is a performance on YouTube of Hess playing it in her later years, for a BBC broadcast. The sound quality is almost comically bad, but her indomitable personality, and her dedication to bringing this music to life, survive the technical flaws: it is well worth seeking out. This book is a fitting monument to that personality and life’s work.

- Myra Hess: National Treasure by Jessica Duchen (£40, Kahn and Averill)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment