The Three Choirs Festival is with us again, for the 283rd year – almost as many, it seems, as The Mousetrap: this year we are in Gloucester. Nowadays, though, this great festival is no longer imprisoned, Barchester-like, in the cathedral close, but ranges all over Gloucester city and Gloucestershire, with concerts also in Tewkesbury, Cheltenham, Highnam and Painswick; and its repertoire is likewise much broader than of yore, with plenty of new music, young artists, children’s concerts, and even, quaintly, a pipe and tabor workshop, to go with the familiar Elgar, Finzi, Vaughan Williams and Holst, the organ recitals and the vicarage tea parties, the coach trips and the memorial talks.

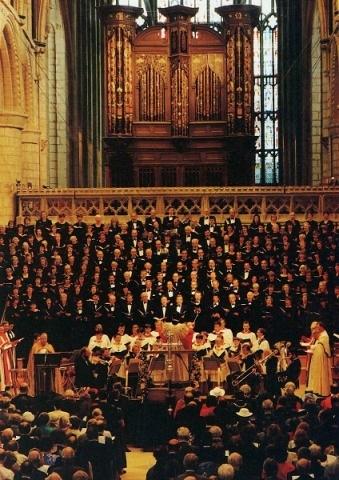

It’s easy to mock. But this is a genuinely local festival that nevertheless casts its net much wider, and which moreover does not, as sometimes in the past, compromise on professional standards. This year’s festival opened on Saturday, with no fewer than five highly contrasted events culminating in a superb account in the cathedral of Elgar’s last oratorio, The Kingdom, a quintessentially Three Choirs work, admittedly, but by no means one that will suffer shoddy or amateurish performance.

First performed at the Birmingham Festival of 1906, The Kingdom isn’t everyone’s cup of vicarage tea: not really mine, to tell the truth. Elgar intended it as the second panel in a triptych begun three or four years earlier with The Apostles. But he struggled to write it, never really found the necessary impetus for a work on this scale, and abandoned any idea of a third panel immediately afterwards. Roger Dubois’ excellent, informative programme note quotes the critic Ernest Newman, advising Elgar against going on with the project and to “turn his mind to other themes. These may bring him new inspiration and a new idiom; at present he is simply riding post-haste along the road that leads to nowhere”. It was a fierce opinion, but Elgar seems reluctantly to have agreed (his next work was a genuine masterpiece, the A-flat symphony).

The problem with The Kingdom is that it has hardly any narrative shape and no dramatic structure at all, though curiously enough it has been staged – heaven knows to what effect. For almost two hours it meanders around and through the same spiritual and musical ideas (many of them already familiar from The Apostles) in a mood that fluctuates – if that’s the word – between the pious benign and the pious stern. There are characters but no characterisation. Mary Magdalene is a saint with no past (unlike her model, Wagner’s Kundry); Peter (Gurnemanz) is the reincarnation of Jesus Christ, his vacillations and denials quite forgotten. As another early reviewer put it, they are like figures in a stained-glass window, forever fixed in attitudes of prayer and exhortation; at the end, everything is the same as at the start, apart from a lot of numb posteriors.

Why stick it out then? Well, Elgar was after all no minor oratorian aspiring beyond his reach, but a genius falling short – something far more interesting. Slice through The Kingdom at any point and you’ll be in the thick of first-rate, sometimes inspired music, brilliantly written for the voice, marvellously orchestrated. Adrian Partington, directing Saturday’s performance, made the most of these qualities, sending glorious orchestral sonorities echoing round the huge Norman columns of this greatest of West Country cathedrals. The Philharmonia Orchestra was on top form, the Festival Chorus immaculately prepared, singing with focus and precision, in music that makes steep demands on their control and coordination.

And the soloists were world-class: Susan Gritton, poised and wonderful as ever, Pamela Helen Stephen, a soprano-ish Mary Magdalene with a silvery edge and real brilliance (Elgar called the part a contralto, but the matronly image is hardly the thing), Adrian Thompson and Roderick Williams, both excellent. Should one praise a singer’s smile? Williams manages to look as if the audience contains only his best friends. One of my friends has a car sticker: "If they haven’t got fishing in heaven, I’m not going." But if the Kingdom has these singers, I might be tempted.

First performed at the Birmingham Festival of 1906, The Kingdom isn’t everyone’s cup of vicarage tea: not really mine, to tell the truth. Elgar intended it as the second panel in a triptych begun three or four years earlier with The Apostles. But he struggled to write it, never really found the necessary impetus for a work on this scale, and abandoned any idea of a third panel immediately afterwards. Roger Dubois’ excellent, informative programme note quotes the critic Ernest Newman, advising Elgar against going on with the project and to “turn his mind to other themes. These may bring him new inspiration and a new idiom; at present he is simply riding post-haste along the road that leads to nowhere”. It was a fierce opinion, but Elgar seems reluctantly to have agreed (his next work was a genuine masterpiece, the A-flat symphony).

The problem with The Kingdom is that it has hardly any narrative shape and no dramatic structure at all, though curiously enough it has been staged – heaven knows to what effect. For almost two hours it meanders around and through the same spiritual and musical ideas (many of them already familiar from The Apostles) in a mood that fluctuates – if that’s the word – between the pious benign and the pious stern. There are characters but no characterisation. Mary Magdalene is a saint with no past (unlike her model, Wagner’s Kundry); Peter (Gurnemanz) is the reincarnation of Jesus Christ, his vacillations and denials quite forgotten. As another early reviewer put it, they are like figures in a stained-glass window, forever fixed in attitudes of prayer and exhortation; at the end, everything is the same as at the start, apart from a lot of numb posteriors.

Why stick it out then? Well, Elgar was after all no minor oratorian aspiring beyond his reach, but a genius falling short – something far more interesting. Slice through The Kingdom at any point and you’ll be in the thick of first-rate, sometimes inspired music, brilliantly written for the voice, marvellously orchestrated. Adrian Partington, directing Saturday’s performance, made the most of these qualities, sending glorious orchestral sonorities echoing round the huge Norman columns of this greatest of West Country cathedrals. The Philharmonia Orchestra was on top form, the Festival Chorus immaculately prepared, singing with focus and precision, in music that makes steep demands on their control and coordination.

And the soloists were world-class: Susan Gritton, poised and wonderful as ever, Pamela Helen Stephen, a soprano-ish Mary Magdalene with a silvery edge and real brilliance (Elgar called the part a contralto, but the matronly image is hardly the thing), Adrian Thompson and Roderick Williams, both excellent. Should one praise a singer’s smile? Williams manages to look as if the audience contains only his best friends. One of my friends has a car sticker: "If they haven’t got fishing in heaven, I’m not going." But if the Kingdom has these singers, I might be tempted.

- The Three Choirs Festival continues until 15 August

- See theartsdesk's UK Festivals 2010 Round-up

Add comment