Leonard Bernstein’s one-act opera Trouble in Tahiti enjoyed a relatively trouble-free gestation, at least compared to his other stage works. Its seven short scenes last around 50 minutes, Bernstein providing his own libretto and completing much of this acerbic, occasionally bitter study of a marriage in crisis whilst on his own honeymoon in 1951.

The edginess is reflected in the music, Bernstein perpetually on the cusp of giving us a jazzy showstopper, only to pull back at the last minute. The big numbers, when they come, are as affecting as anything Bernstein ever wrote – especially a Satie-like duet near the close, and a heart-stopping aria (“I was standing in a garden”) sung by the wife, Dinah. Dinah, played by Sandra Piques Eddy in this Opera North revival of Matthew Eberhardt’s 2017 staging, looks as if she has it all: a young son, a well-equipped suburban home and a successful husband, Sam (Quirijn de Lang). Alas, the latter is a self-obsessed boor, more interested in winning a handball tournament than remembering his son’s birthday or showing any affection towards his wife.

Tahiti’s signature sound is that of the vocal trio (Laura Kelly-McInroy, Joseph Shovelton and Nicholas Butterfield), their pastiche radio jingles extolling the joys of consumerism and filling in bit parts as required. Charles Edward’s set quickly flips from kitchen to office to doctor’s surgery; this production has plenty of zip and pizzazz. De Lang embodies Sam’s shallowness, soaking up compliments from sycophantic colleagues and coldly rejecting a secretary he’s enjoyed a #MeToo moment with. The scene where Sam gloats after winning the handball trophy could so easily be comic were the lyrics supplied by Comden and Green; as things stand, he’s a heel.

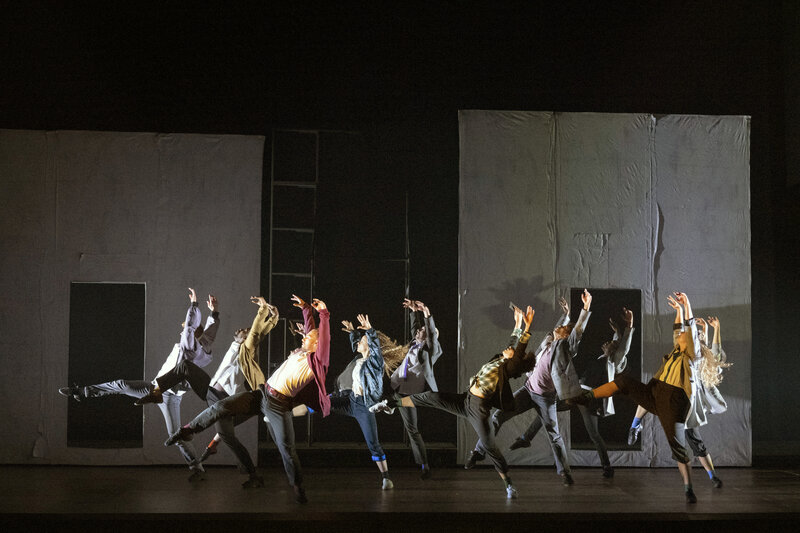

Eddy’s downtrodden Dinah is more sympathetic. Her voice is sometimes drowned out when conductor Antony Hermus lets rip, but she’s superb in her showstopping “What a movie!”, a number as exuberant as anything in Bernstein ever wrote. Isaac Sarsfield throws in a winning wordless cameo as the couple’s son, and the ambivalent, unresolved close packs a real punch, prefiguring the ending of West Side Story five years later. This is an emotionally powerful, lucid production of a work which deserves to be better known; the 2017 incarnation is available to stream but you really need to see Trouble in Tahiti live. This double bill is Opera North’s second collaboration with fellow Leodensians Phoenix Dance. South African choreographer Dane Hurst’s take on the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story is loosely set in late 1950s-early 60s South Africa, when apartheid legislation segregated whole communities and prohibited interracial relationships. The results are exciting; Dane outlines the links between Tahiti and Symphonic Dances in a programme essay, seeing both pieces as portraits of fractured relationships and communities ripped apart. Dancers unite, spar and squabble, the Tahiti set repurposed as an austere whitewashed building façade which transforms again in the final seconds.

This double bill is Opera North’s second collaboration with fellow Leodensians Phoenix Dance. South African choreographer Dane Hurst’s take on the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story is loosely set in late 1950s-early 60s South Africa, when apartheid legislation segregated whole communities and prohibited interracial relationships. The results are exciting; Dane outlines the links between Tahiti and Symphonic Dances in a programme essay, seeing both pieces as portraits of fractured relationships and communities ripped apart. Dancers unite, spar and squabble, the Tahiti set repurposed as an austere whitewashed building façade which transforms again in the final seconds.

That the dances don’t follow the musical’s action is irrelevant. Hermus secures pungent, incisive orchestral playing; how much punchier this score sounds in a dryish theatre acoustic. Dane prefaces the work with Halfway and Beyond, a 10-minute recitation by Leeds poet Khadijah Ibraham touching on conflict and division, paired with dance and a viscerally effective percussion accompaniment. It’s arresting, but hard to assimilate on just one viewing – you wish that Ibraham’s text could be printed in the programme or displayed as surtitles.

Add comment