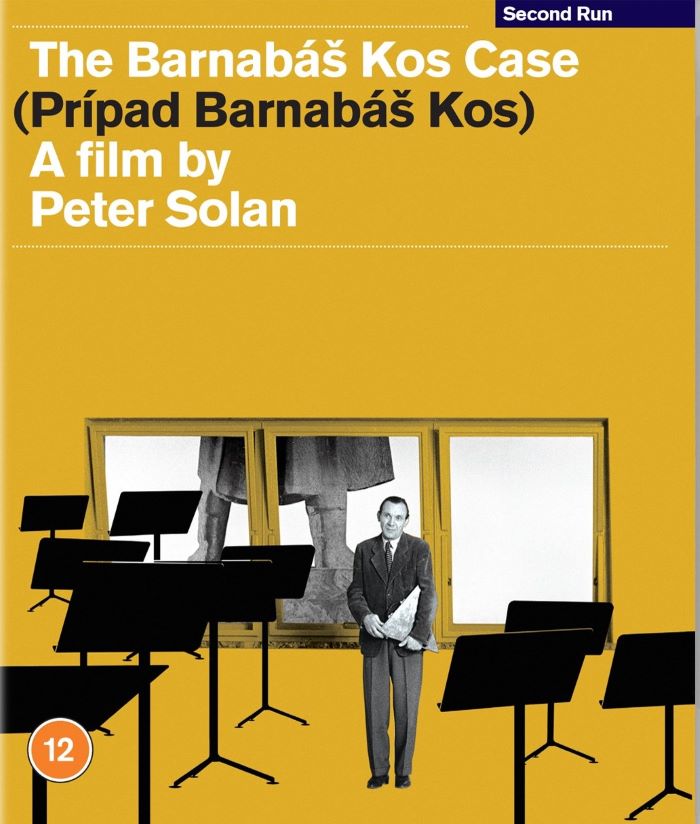

One of The Barnabáš Kos Case’s incidental pleasures lies in its relatively accurate depiction of orchestral life. Much of the action in Peter Solan’s 1964 Slovak black comedy (originally title: Prípad Barnabáš Kos) takes place in a rehearsal studio, one filled with real, non-miming musicians. Actor Milivoj Uzelac, playing one of the conductors, was also a composer and actually looks convincing on the podium.

If I’m allowed to be pedantic, the most glaring false note is the role played by the titular antihero; you’d never find a percussionist who only plays the triangle, let alone one who carries his instrument about in a bespoke case. Josef Kemr’s downtrodden Barnabáš Kos is initially a likeable nobody (an “inept loyalist” in Peter Strickland’s words), filling his waking hours with civic-political engagements: campaigning, serving on committees and volunteering – activities which invariably mean that he’s late for rehearsals, any solos dutifully filled in by a fellow percussionist. Solan based his screenplay on a popular short story by Peter Karvaš, the triangle a perfect match for a one-note character with no hidden depths or talents.

Alas, Kos’s “zeal, discipline and modesty” bring him to the attention of his superiors. He receives a letter promoting him to the role of orchestral director, something he’s convinced has been sent in error. There’s a surreal sequence showing Kos in an unnamed government building attempting to find the truth, its pristine white corridors and lines of doors pre-dating the elaborate sets constructed for Jacques Tati’s Playtime. Kos soon gains an attractive secretary (Jarmila Košťová) plus a swish office.

Initially Kos is ridiculed by his fellow musicians and clearly misses his former role, and his slow transformation from underdog to zealot is wonderfully handled. Solan and production designer Ivan Vaníček pepper the film with triangular forms: look out for fabric designs, tables and strap handles in a Bratislava trams. Even the orchestra’s layout is a triangle, and Kos’s obsession leads him to commission a new triangle concerto, orchestral players’ notes are limited as an act of deference. There’s a bizarre scene filmed in a steelworks, the wild-eyed Kos desparate to possess the best solo instrument imaginable and scrapping those which fall short. Kos is clearly unhinged at this point but Kemr’s performance makes us retain a shred of affection for him, the inevitable fall from grace a relief both for us and the orchestra. Kos’s betters dig into a post-concert buffet and discuss their protégé’s performance, one man pointing out that the orchestra’s accounts were never been so clear and detailed as they were under Kos.

Initially Kos is ridiculed by his fellow musicians and clearly misses his former role, and his slow transformation from underdog to zealot is wonderfully handled. Solan and production designer Ivan Vaníček pepper the film with triangular forms: look out for fabric designs, tables and strap handles in a Bratislava trams. Even the orchestra’s layout is a triangle, and Kos’s obsession leads him to commission a new triangle concerto, orchestral players’ notes are limited as an act of deference. There’s a bizarre scene filmed in a steelworks, the wild-eyed Kos desparate to possess the best solo instrument imaginable and scrapping those which fall short. Kos is clearly unhinged at this point but Kemr’s performance makes us retain a shred of affection for him, the inevitable fall from grace a relief both for us and the orchestra. Kos’s betters dig into a post-concert buffet and discuss their protégé’s performance, one man pointing out that the orchestra’s accounts were never been so clear and detailed as they were under Kos.

This film is an offbeat treat: visually interesting, well-acted and handsomely scored by Pavol Simai. We’re living at a time when the world seems to be run by those least qualified to do so, Kos’s central message all the more pertinent. Second Run’s production values are well up to scratch, with excellent booklet essays and interesting bonus features. Viktor Kubal’s tiny animated short Promotion offers another warning about the dangers of giving the incompetent more responsibility, and we get to watch Jarmila Košťová looking for a parking place in a congested early 1970s Bratislava.

Add comment