British audiences of a certain age will note Finis Terrae’s similarity to Finisterre, one of the 31 sea areas listed in the BBC’s Shipping Forecast. Or previously listed – it was renamed Fitzroy in 2002 to avoid confusion with another Finisterre off the coast of Spain.

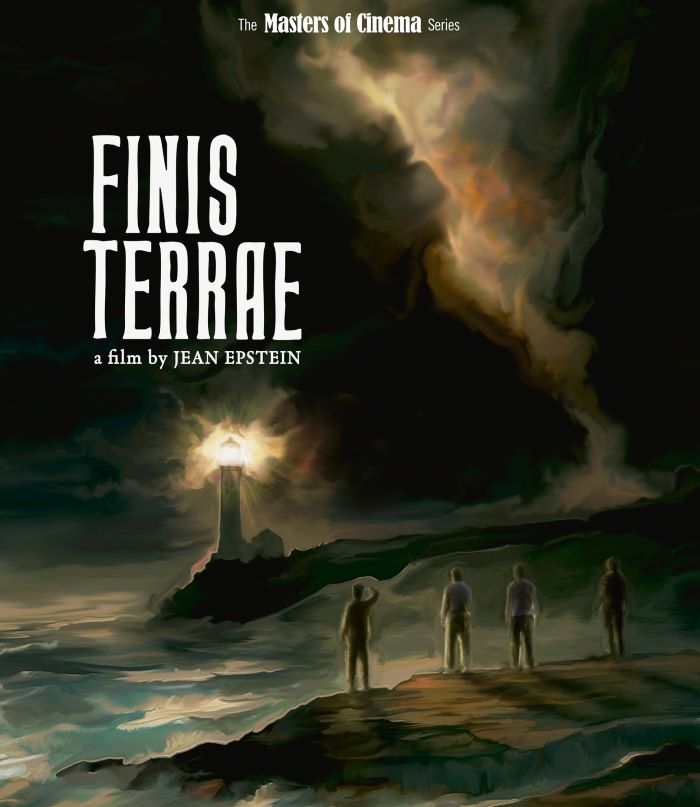

This title translates as "End of the Earth", an apt one for a silent film which depicts a community and way of life largely untouched by the industrial revolution. Director Jean Epstein had recently completed an acclaimed but troubled 1928 adaptation of Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher. Feeling exhausted and burnt-out, he left Paris and headed west to the Breton island of Ushant, bringing with him two silent cameras, a tiny crew and a miniscule budget.

Epstein’s sincerity helped him gain the trust of the Ushant residents, the plan being to devise a scenario with the residents’ help and use untrained locals as leads. The plot follows four men who have made the annual summer trip to the barren, uninhabited island of Bannec to collect and burn kelp, the resultant ash a valuable fertiliser. The work is dangerous and unpleasant, the thick plumes of smoke visible from Ushant. Ambroise Rouzic and Jean-Marie Laot are superb as the two central characters, childhood friends whose relationship sours when Ambroise accidentally drops and smashes a bottle of wine, badly cutting his thumb on a shard of glass. Meanwhile, Jean-Marie loses his penknife, convinced that Ambroise has stolen it.

Epstein’s sincerity helped him gain the trust of the Ushant residents, the plan being to devise a scenario with the residents’ help and use untrained locals as leads. The plot follows four men who have made the annual summer trip to the barren, uninhabited island of Bannec to collect and burn kelp, the resultant ash a valuable fertiliser. The work is dangerous and unpleasant, the thick plumes of smoke visible from Ushant. Ambroise Rouzic and Jean-Marie Laot are superb as the two central characters, childhood friends whose relationship sours when Ambroise accidentally drops and smashes a bottle of wine, badly cutting his thumb on a shard of glass. Meanwhile, Jean-Marie loses his penknife, convinced that Ambroise has stolen it.

Harsh winds and thick fog typify the characters’ struggle against a hostile natural world, Ambroise’s injured thumb ultimately leaving him face-down in the sand, his companions mistakenly accusing him of laziness. When Jean-Marie belatedly realises that his former friend is genuinely ill, a sudden lack of wind means that he’s unable to sail to Ushant to seek medical help. Epstein’s documentary-style depiction of the Ushant community is absorbing: though the main settlement is a small village, it feels like a vast metropolis after the emptiness of Bannec.

The island’s black-clad women scurry like insects, the hostility between the two boys’ mothers made clear. And look out for a glimpse of children singing into a wax cylinder recorder, their Breton language on the cusp of extinction. Finis Terrae is as much cinematic anthropology as simple narrative. Epstein’s visual style is bold, making poetic use of closeups (pictured below). Shooting with hand-held cameras gives much of the footage a disconcertingly modern feel, Ambroise’s delirium conveyed via oblique camera angles and quick cuts. One of the last French silent films (it was released in 1929), Finis Terrae looks magnificent in this 4K restoration. It’s a neglected gem, and surely an influence on films as diverse as Michael Powell’s The End of the World and Mark Jenkins’ Bait. Bonus features are generous, Pamela Hutchinson’s compact survey of Epstein’s life and work especially useful. And Christophe Wall-Romana’s booklet essay unpicks the film in entertaining detail, recalling how moved the Ushart inhabitants were by their on-screen depiction, the younger extras astounded to see themselves on screen.

One of the last French silent films (it was released in 1929), Finis Terrae looks magnificent in this 4K restoration. It’s a neglected gem, and surely an influence on films as diverse as Michael Powell’s The End of the World and Mark Jenkins’ Bait. Bonus features are generous, Pamela Hutchinson’s compact survey of Epstein’s life and work especially useful. And Christophe Wall-Romana’s booklet essay unpicks the film in entertaining detail, recalling how moved the Ushart inhabitants were by their on-screen depiction, the younger extras astounded to see themselves on screen.

Add comment