The German director Robert Wiene is best known for The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (1920), perhaps the most influential piece of expressionist cinema. He's not as well known as F. W. Murnau or Fritz Lang, but he deserves to be in the same league. The Hands of Orlac (1924), made in Austria rather than Germany, is a very fine example of a cinema haunted by the violence and death of the First World War, and containing within it both seeds of fascist aesthetics and the darkness that characterises film noir.

Based on a novel by the French author Maurice Renard, this intense and dramatic film tells the tragic story of a concert pianist, Paul Orlac, whose hands are destroyed in a train crash, and replaced by the hands of a recently guillotined murderer, Vasseur. The unfolding drama is shot through with a mixture of horror and poignancy.

Orlac gradually becomes a monster, but the torment of his voyage resonates with what makes us human – we feel for him at every stage of the tragedy that plays out on the screen. The narrative at times avoids strict linearity; in this Wiene is making cinema rather than filming theatre. He takes us through a dark labyrinth, confounding us with twists and turns, in which reality and fantasy are purposefully confused, not least as a reflection of the tragic hero’s increasingly disturbed psyche.

The film alludes to a number of themes, inducing the mind-body conundrum, the mixed blessing offered by medical science, a son’s urge to kill his father, and a wife’s faith and love. But Orlac and his tormented transplants are the main focus, the former pianist's ordeal a door that opens to the human abyss that the film so relentlessly uncovers.

Conrad Veidt is the film’s anti-hero, victim and star. The actor had made his name in the movies playing Cesare, the spooky and murderous somnambulist in Caligari. Here, he gives a show-stopping performance as the pianist who gradually becomes possessed by the murderer’s spirit, realising he can no longer play Chopin, but finding himself compelled instead to enact Vasseur's impulses.

As Orlac is pulled into the deep well of humanity’s capacity for evil, the passion that once drove his music-making is slowly transformed into something much darker, and Veidt makes this descent into psychological and emotional hell sometimes hard to watch.

There are moments when Veidt seems to be channelling the French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot’s "hysterical" women at La Salpétrière teaching hospital. He is a master of stylised physical theatre, part of the same 1920s movement that brought to the fore the expressionist choreography of Rudolf Laban, the Ausdruckstanz (Expressionist Dance) devised in Laban’s wake by Kurt Jooss, who was eventually to train Pina Bausch.

Veidt slow-dances as much as he acts – contorting his body and allowing the spirit of murderous violence that lies buried in the heart of everyman, as much as the capacity for love, which in the film is incarnated by Orlac's resolutely loving wife. The dark energy he embodies seems to flow through his twisted hands and fingers. The stylisation of his gestures suggests as much the twisted agony and erotic passion of Egon Schiele’s pre-war drawings and paintings as it does the dance-theatre that was evolving at the time.

Veidt’s portrayal of possession, his eyes bulging with a mix of caricatured horror and tortured self-doubt, prefigures Peter Lorre’s unforgettable performance as the hunted murderer in Fritz Lang’s masterpiece M: psychological territory in which universal unconscious forces are played out, an unholy mix of angst and perverse desire, explaining in part the lasting appeal of the netherworld of noir and the portrayals of homicidal violence that has always mirrored our secret desires on the movie screen.

The action mostly takes place – not surprisingly, given the genre – at night. The memorable opening sequence evokes with vibrant horror the train wreck in which Orlac's hands are crushed, a remarkable feat of lighting, framing, action and editing that brings thrilling drama to the screen in spite of the absence of a single camera movement. The interiors, while not as stylised as those in Caligari, make the most of light and dark and provide a psychological space that reflects the inner turmoil of the film’s main characters.

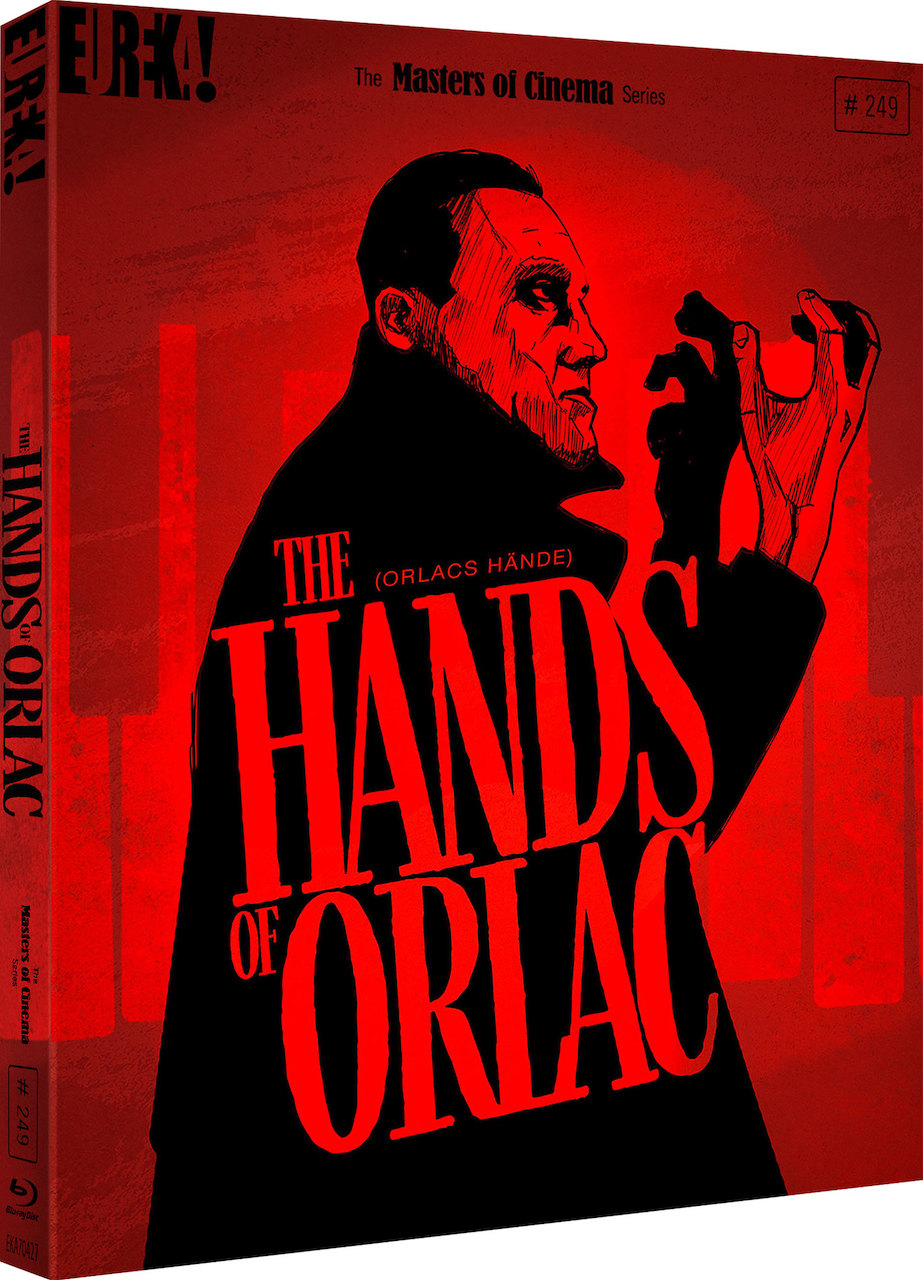

The Blu-ray release – a fine restoration from Film Archiv Austria – features some excellent bonuses including an alternative longer version of the film, a slightly pedestrian but serviceable video essay from David Cairns and Fiona Watson, and – best of all – a booklet that includes two illuminating short essays: one by Philip Kemp, with a vindication of Wiene, and the other by Tim Lucas on the context of Maurice Renard’s original book.

Add comment