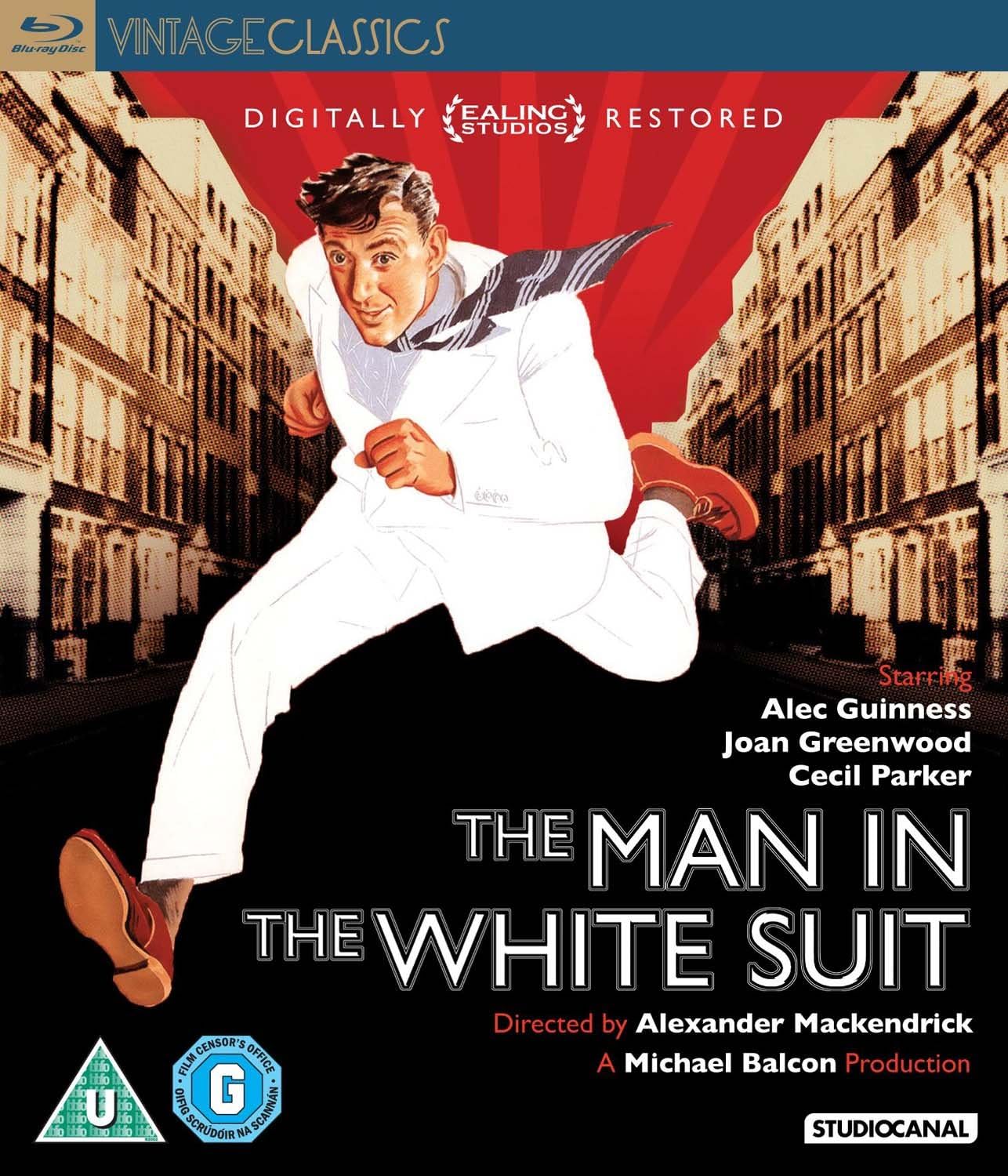

The best Ealing comedies are surely the three darkest: specifically Kind Hearts and Coronets, The Ladykillers and The Man in the White Suit. The latter pair were helmed by Alexander Mackendrick, a cosmopolitan director who’d arrived at the studios with a thorough understanding of trends in mainstream European and American cinema.

Take the final act of The Man in the White Suit: watched with the sound turned down: it’s an expressionist noir thriller, Alec Guinness’s naïve scientist Sidney Stratton pursued through the streets at night by a vengeful mob, cinematographer Douglas Slocombe making Burnley resemble Berlin.

The screenplay was adapted from an unproduced play by Mackendrick’s cousin Roger MacDougall, about the creation of a revolutionary indestructible fabric which never needs cleaning.

The screenplay was adapted from an unproduced play by Mackendrick’s cousin Roger MacDougall, about the creation of a revolutionary indestructible fabric which never needs cleaning.

Guinness’s Stratton is initially a shadowy presence, a Cambridge-educated scientist taking on menial jobs in Lancashire textile mills in order to use their research facilities. Early shots of smoky, polluted skies, cobbled streets and factory floors are documentary-like, showing a beaten-up, dilapidated nation that’s a long way from the promised postwar utopia. Who wouldn’t want to transform this landscape for the better?

Stratton’s chief flaw is his narrow outlook, an inability to understand that his brilliant invention will put thousands of textile workers out of work and cause economic chaos. Scientific progress is always double-edged, and it’s telling that the film was released in 1951, six years after the bombing of Hiroshima. One of the best lines comes in the final minutes, Edie Martin’s washerwoman confronting Stratton, asking him “Why can’t you scientists leave things alone?"

Serious subtext aside, this is frequently a very funny film. Guinness could be an excellent physical comedian, the script giving him plenty of opportunities to run, jump and knock things over.

I’d forgotten the sound effect used when Stratton’s laboratory equipment is in action, the iconic "Guggle Glub Gurgle" created by sound editor Mary Habberfield, the bubbling noise produced by blowing a straw into a glycerin solution. Cecil Parker’s mill owner Birnley bankrolls Stratton’s research, initially envisaging just the profits, rolling his eyes as successive explosions cause more and more damage, Stratton and his assistant hiding behind a wall of sandbags each time they initiate a chemical reaction. The supporting cast is excellent: German actor Olaf Olsen has a wonderful cameo as Birnley’s butler, and Ernest Thesiger is both comical and terrifying as an elderly tycoon. Standing out amongst the suits and lab coats are two strong female characters. Joan Greenwood plays Birnley’s husky-voiced daughter Daphne, brushing up on her chemistry to better understand what Stratton is up to. Daphne is the first character to sense the new fabric’s potential for chaos, staring at Stratton as he shows off his titular outfit, noting that “the suit looks like it’s wearing you.” Equally good is Vida Hope as Bertha (pictured above, right), a politically savvy and compassionate mill worker torn between her admiration for Stratton and her responsibilities as a trade union member.

Standing out amongst the suits and lab coats are two strong female characters. Joan Greenwood plays Birnley’s husky-voiced daughter Daphne, brushing up on her chemistry to better understand what Stratton is up to. Daphne is the first character to sense the new fabric’s potential for chaos, staring at Stratton as he shows off his titular outfit, noting that “the suit looks like it’s wearing you.” Equally good is Vida Hope as Bertha (pictured above, right), a politically savvy and compassionate mill worker torn between her admiration for Stratton and her responsibilities as a trade union member.

Studio Canal’s new 4K restoration is impressive, and the disc comes with enticing bonus features, including a useful commentary by film historian Dean Brandum and a charming animated short about tea, its text provided by Roger MacDougall. Especially useful and entertaining is an introduction by Matthew Sweet discussing the film in its historical context and noting that the creation of Stratton’s magical solution resembles a nuclear explosion.

Add comment