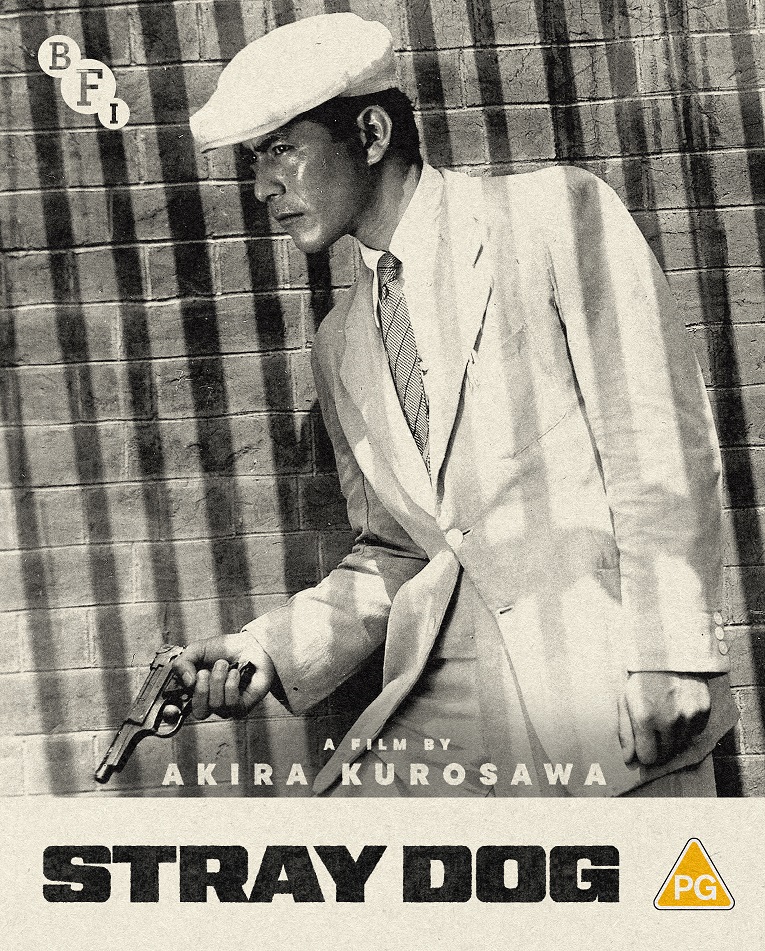

Kurosawa’s 1949 thriller probes post-war morality in a Tokyo whose ruins and US occupation mostly remain just out of shot, in a heatwave causing mistakes and madness. The theft of callow detective Murakami (Toshiro Mifune)’s police pistol on a crowded trolleybus and his guilty hunt for what becomes a murder weapon provide the narrative, and sharp-featured young Mifune’s coiled performance, alternating mimed grace with feline fierceness, is the arrow carrying it to its bruising conclusion.

Kurosawa and Mifune are still defined in the West by Rashomon and Seven Samurai, breakthrough Fifties releases exotically set in feudal Japan, but Stray Dog was the director’s third straight contemporary feature with Mifune, made when US censors anyway suspected such period tales of inspiring Imperial Japan’s ethos. It’s the flipside of Mifune’s explosive gangster in Drunken Angel (1948), and a forerunner to Kurosawa’s penultimate film with him, the bifurcated moral drama and police procedural High and Low (1963). Influenced by the naturalistic location shooting of Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948) and Georges Simenon’s humane crime novels, Stray Dog parallels the film noirs darkly blooming in post-war Hollywood, but is a more panoramic investigation of a scarred country.

Kurosawa and Mifune are still defined in the West by Rashomon and Seven Samurai, breakthrough Fifties releases exotically set in feudal Japan, but Stray Dog was the director’s third straight contemporary feature with Mifune, made when US censors anyway suspected such period tales of inspiring Imperial Japan’s ethos. It’s the flipside of Mifune’s explosive gangster in Drunken Angel (1948), and a forerunner to Kurosawa’s penultimate film with him, the bifurcated moral drama and police procedural High and Low (1963). Influenced by the naturalistic location shooting of Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948) and Georges Simenon’s humane crime novels, Stray Dog parallels the film noirs darkly blooming in post-war Hollywood, but is a more panoramic investigation of a scarred country.

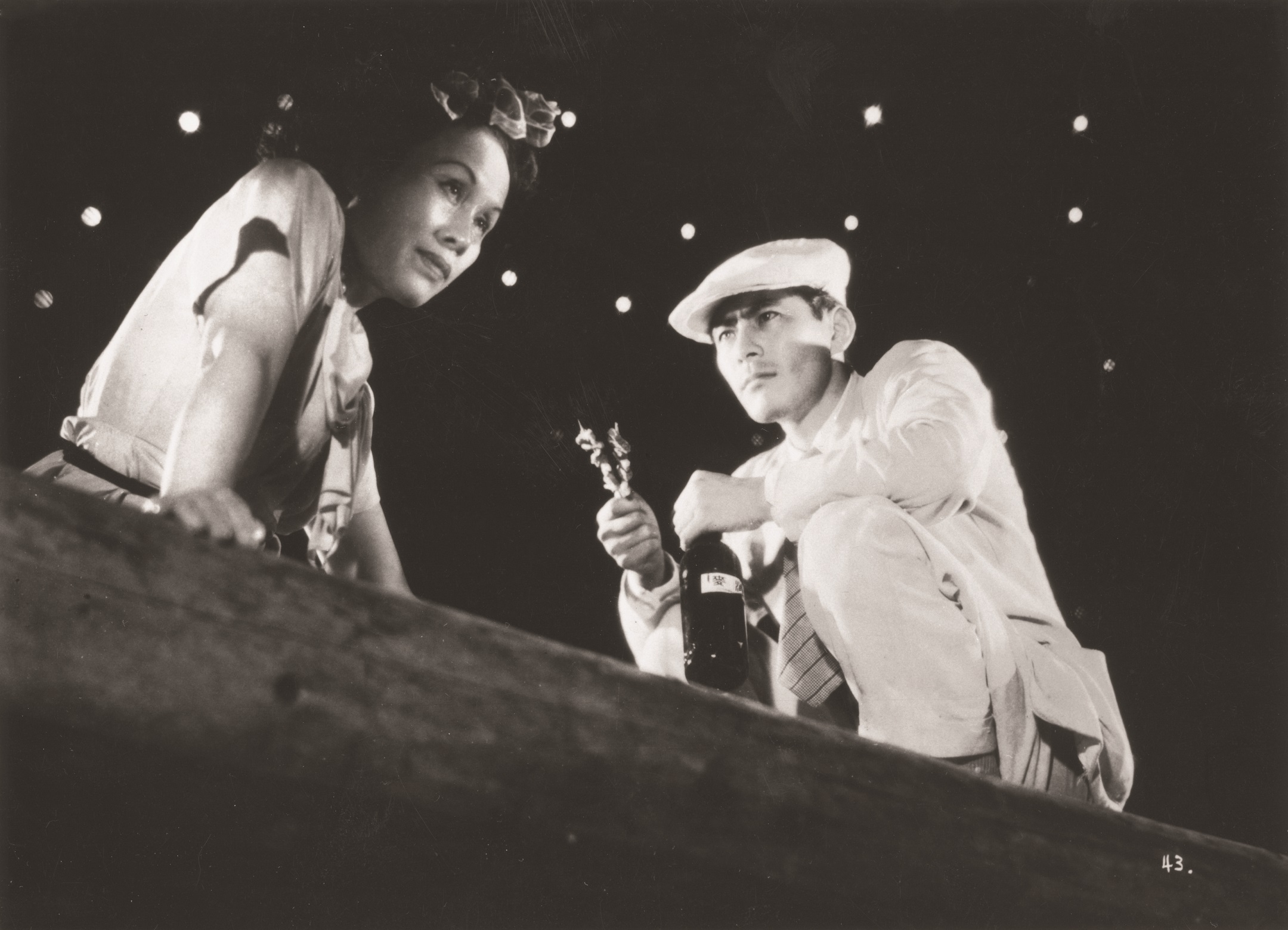

Kurosawa’s mastery of set-pieces is seen during a 10-minute montage with Murakami, disguised as a destitute, footsore war veteran, prowling cramped alleys and wide suburban avenues, the white sun bleeding through a latticed awning and midday shadows gridding backs. Though Kurosawa otherwise mostly shot on sets, the oppressive reality of high summer in defeated Tokyo is glimpsed in shacks and suggestively absent houses. Clothes stick, sweat stains, the city feeling both claustrophobic and a dusty wasteland. Famio Hayasaka’s musical montage of Japanese then jazz-like Western music reinforces the camera’s progress towards an arcade’s young Americanised regulars, as if rushing through time. The sequence was shot by 2nd Unit director Ishirō Honda, five years before his veiled Atom Bomb riposte Godzilla. Another white-knuckle sequence sees Murakami and his worldly, paternalistic superior Inspector Satō (Takashi Shimura, later the cancer-ridden bureaucrat in Kurosawa’s 1952 Ikiru) hunt a suspect at a packed baseball stadium. There’s Hitchcock-worthy tension as the detectives later separate, connected only by a phoneline as the pistol’s murderous recipient shoots one and the storm breaks in drowning rain.

Another white-knuckle sequence sees Murakami and his worldly, paternalistic superior Inspector Satō (Takashi Shimura, later the cancer-ridden bureaucrat in Kurosawa’s 1952 Ikiru) hunt a suspect at a packed baseball stadium. There’s Hitchcock-worthy tension as the detectives later separate, connected only by a phoneline as the pistol’s murderous recipient shoots one and the storm breaks in drowning rain.

As in High and Low, the police are diligent and genteelly soft-spoken, embodied by Satō and his modest suburban home, where he and the younger Murakami sit on the porch discussing post-war society into the night. “He’s always blaming the world, the war,” they’ve been told of their suspect, Yusa, an embittered young veteran. This is their murderous stray dog, yet Murakami can’t help but sympathise with his fellow veteran: “During the war, I saw so many men turn into an animal at the slightest provocation.”

Along with a glimpse of US soldiers in a military vehicle (cinema evidence of the occupation was banned), here is an indication of what happened, the bloody crime buried beneath this crime film’s civilised police work. Yusa is the rabid reminder. When he and Murakami finally meet, they grapple in what seems like jungle close to suburban lawns, a last battle screened from civilians, till the tortured killer screams. Stray Dog is a seedily beautiful snapshot of Japan approaching American-sponsored resurrection while still a crime scene.

Add comment