Schubert’s Fifth Symphony is one of those pieces whose existence in the modern world hangs on the most tenuous of threads. After its posthumous premiere the score was lost for half a century before a set of parts resurfaced, and the work was saved for posterity. I’d hate to imagine a world without Schubert’s Fifth in it, and will never turn down a chance to hear it live, hence a trip to Milton Court to hear the Britten Sinfonia give it a cheerfully loving reading, as the finale of a programme that also featured Schubert’s inspiration, Mozart, and two contemporary pieces.

Before we got to the Schubert we had Elena Kats-Chernin’s vigorous Fast Blue Village 5, for strings alone, which barrelled along, with its lop-sided 5 beat patterns constantly switching tack. It’s in a Karl Jenkins-like, looping minimalist language – I also heard echoes of Piazzolla – and was played with energy and a meaty string sound. It’s a piece I can imagine some people hating, but I loved it, apart from the unexpected and somehow unsatisfactory final resolution.

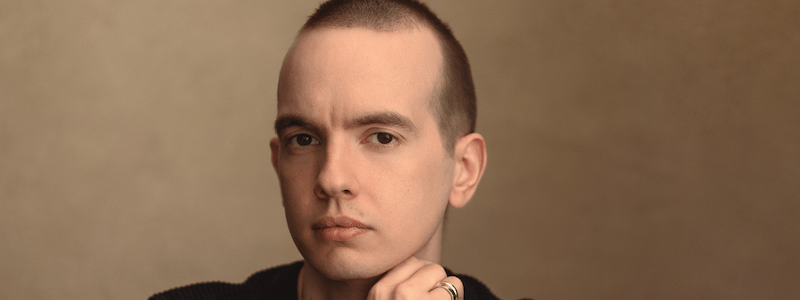

Jeneba Kanneh-Mason played Mozart’s 23rd Piano Concerto, one of his most charming works, genial outer movements sandwiching a delicate and tender Adagio. I didn’t love all of Kanneh-Mason’s playing, which lacked a bit of grace, the last movement brisk to the point of being brusque. But her co-ordination with the unconducted ensemble was deft and her playing of the slow movement, with its chromatic byways, was eloquent and well-judged. Kanneh-Mason’s lovely, limpid encore, William Grant Still’s Summerland, felt more like home turf, her connection with the music evident. The second half opened with Robin Haigh’s Grin, a quirky, enjoyable piece, scored with cute attention to detail and a real feel for texture. For the only time in the evening the lack of a conductor was felt. Despite leader/director Jacqueline Shave’s best efforts there were a couple of slightly wobbly moments in the middle section, where the music in any case lost me a bit. But on the whole I really liked Grin, from the tentative, quizzical opening of string pizzicatos and glissandos, to the final gallop, which built up quite a head of steam. The musical language was contemporary, but with Mozartian wind chords sitting under the surface, and I found it very engaging.

The second half opened with Robin Haigh’s Grin, a quirky, enjoyable piece, scored with cute attention to detail and a real feel for texture. For the only time in the evening the lack of a conductor was felt. Despite leader/director Jacqueline Shave’s best efforts there were a couple of slightly wobbly moments in the middle section, where the music in any case lost me a bit. But on the whole I really liked Grin, from the tentative, quizzical opening of string pizzicatos and glissandos, to the final gallop, which built up quite a head of steam. The musical language was contemporary, but with Mozartian wind chords sitting under the surface, and I found it very engaging.

Then came the Schubert. If Robin Haigh offered a mischievous grin, the Schubert is one massive beaming smile, like the one plastered all over my face for the duration. The symphony is so effortlessly winning, whether in its sunny first theme, a witty dialogue between violins and cellos, the ersatz Sturm und Drang in the Mozartian Menuetto, like a child pretending to be a monster, or the Andante, the emotional heart of the piece, forever veering into new harmonic territory before finding its way back. The Britten Sinfonia were great, especially the pocket-sized wind section, with the two bassoons offering real colour and character. “Symphonic chamber music” may be an oxymoron, but it’s what this piece is. As such it’s perfect repertoire for the Britten Sinfonia, and they did it justice.

Add comment