There are still pockets of musical snobs who want to keep Elgar's two symphonies for the English, and off the worldwide roll call of orchestral masterpieces. Yet a steady line of international conductors - from Solti and Svetlanov to Haitink and Previn - has proved them the adventurous equal of anniversary composer Mahler's symphonic giants. Now Vladimir Ashkenazy joins the ranks. Elgar may not yet be quite in his bloodstream in the same way as Rachmaninov and Sibelius, but in yesterday afternoon's concert there was enough love for the complex composer's introspective side to set the Russian on the right, tender tracks.

As warm-up act, we were first presented with the cheeky chappies and sentimental blokes of Elgar's Cockaigne Overture. Ashkenazy, a benign and hyperactive presence from the start, encouraged supple Philharmonia strings to make the most of the ingeniously wrought inner lines, reflected in a simpler context by the bonny, horn-led counterpoint which joins the vivacious fiddle-and-flutes duet-finale of Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto. James Ehnes, whose Philharmonia partnership with Andrew Davis in the Elgar Concerto was one of my highlights of the musical noughties, kept up impeccable intonation and never dropped a stitch in a work whose non-stop demands always take me by surprise. He knew when to give a bit more space to the fierier moments, but never sacrificed musical sense and line to virtuosity. The same was true of the Paganini Sixteenth Caprice he bent to his intelligent will as an encore.

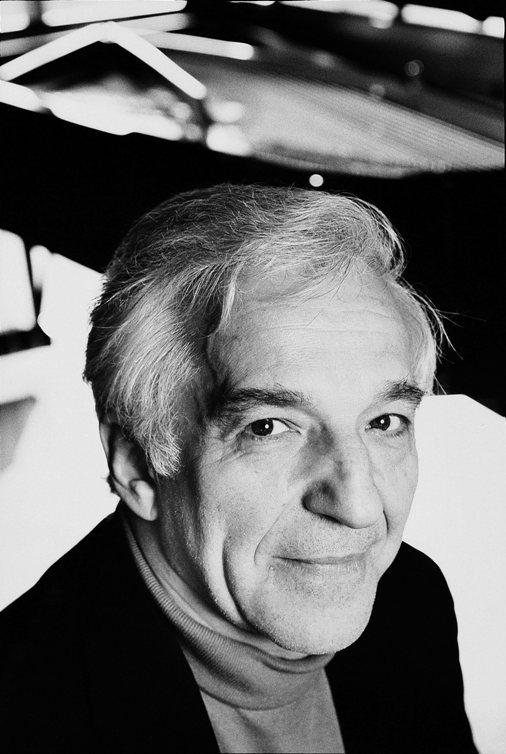

"Fantastic" mouthed the maestro, a slightly surprised look on his face, to his leader at the end of the concert. As well he might after the First Symphony's passionate journey of a soul, one of several which stand out in Elgar's output, had ended in the most brilliantly scored of victories. If there was a sense that the noble motto theme which finally triumphs over insecurity could sometimes have been more inscaped, no such reservations could apply to the great Adagio, fluently wrought out of a hectic scherzo to become the most sheerly beautiful slow movement since the one in Beethoven's Ninth. Ashkenazy underlined its passing ghosts - the dark, Wagnerian brass chords, the timpani doombeats - but left us in no doubt that Elgar had become happily lost to the world in the private peace of its closing bars. In the trouble and strife of the outer movements, his volatility followed on the heels of Solti, but already there was more depth in an interpretation which still has time to grow. Let's hope Ashkenazy goes to to tackle the even more riven Second Symphony.

- Check out what's on in the South Bank Centre season

- Check out what's on in the 2010 Edinburgh International Festival - Ashkenazy conducts the Sydney Symphony Orchestra

Add comment