Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre is making one of its regular stops in Europe (the company tours commitedly: not only in the USA, but more than two months of each year are spent bringing their bravura dance style to the world). It is to their enduring credit, then, that their performances look as fresh and as spontaneous as they do.

In Hymn, artistic director Judith Jamison’s tribute to Ailey, her mentor and the company’s founder, she tells, in voice-over, of loving "spectacle, yes", but also "social statements, yes", wanting to transmit not only Ailey’s own "blood memories", his lines of descent both in the dance and in the black tradition. And, most important, she "wants to transmit through discipline" – discipline, that element that makes up every dancer’s daily life: dance is discipline.

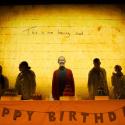

It is a touching and revelatory moment. Hymn opens with an empty stool in a pool of light, and Ailey’s voice recounts his early influences and his own aims. But unfortunately, while the company that is then revealed as the stage bursts into light (pictured below) – the "large black company that celebrates the black experience", as Ailey puts it – is a wonderfully honed instrument, Hymn is overlong and poorly conceived, a patchwork of good intentions, rather than a single-focused piece of choreography. Its insistently bumpy tone is set by a series of interviews with Ailey dancers (all now long retired), which in turn are narrated to us by the voice of the actor Anna Deavere Smith, whose somewhat nasal tone mimics their stutters, dropped words, repeated tics and mannerisms (I lost count after the seventh "you know", and the third "whatever").  The piece is further hindered by a rather dull score by Rober Ruggieri, heavily but intermittently percussive, and choreography that is curiously stop-start: together this gives the dancers little to work with, although they do what they can with this thin stuff. Rachael McLaren had the best of it: Jamison’s choreography, linked to the narrated memory of the original dancer’s African grandmother, is fluid, slightly feline, and McLaren revelled in it. One of Ailey’s longtime stars, Linda Celeste Sim, also did fine in the "Black Dress" solo.

The piece is further hindered by a rather dull score by Rober Ruggieri, heavily but intermittently percussive, and choreography that is curiously stop-start: together this gives the dancers little to work with, although they do what they can with this thin stuff. Rachael McLaren had the best of it: Jamison’s choreography, linked to the narrated memory of the original dancer’s African grandmother, is fluid, slightly feline, and McLaren revelled in it. One of Ailey’s longtime stars, Linda Celeste Sim, also did fine in the "Black Dress" solo.

She did more than fine, however, in Christopher Huggins’s new piece, Anointed. Huggins, an ex-Ailey dancer himself, knows what they can do, and his choreography works to show them off. Sims and Jamar Roberts open on a slow, meditative pas de deux of longing and loss. Sims is a dancer of some weight and grandeur, and Huggins’s choreography allows her to unfold and expand, like the grand figurehead on the prow of a ship facing into the light. She exits to a sense of loss and passing, before returning, now sassily dressed in bright fuchsia and, with a cohort of four equally glam women, goes on the razzle. The driving, thrilling music, by Moby and Sean Clements, allows the dancers to let loose in a way Jamison’s more subdued work does not: this is what Ailey dancers are trained for, and their relief and joy at the release communicates itself to the audience. The evening finishes, as always at an Ailey performance, with Ailey’s Revelations, to ten gospel numbers (pictured left and top). That the dancers perform this with all their souls, without any sense that this is a chore to be waded through, is astonishing, yet a miracle they repeat every night. Revelations is, as always, a joy, and permits the sighting of a number of new talents, as well as a welcome return to more established stars. Akua Noni Parker and Amos J Machanic, Jr, in “Fix Me, Jesus” make a wonderful new partnership: Machanic is always a pleasure to watch, and Parker, with a classical ballet background, as well as having a lovely line, brings great dignity to the role – her deep, lush arm movements, from the very depth of her spine, are thrilling, like a great bird opening to its full wing-span. The three virtuoso men in “Sinner Man” – Jermaine Terry, Yannick Lebrun and Michael Francis McBride – brought the house down; and one uncredited man in “Rocka My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham” made the hair rise on the back of my neck: it was not that he danced any better than anyone else, but just like Fred Astaire, he had that extra snap, that tiny, precise finish to each movement, that made looking at anyone else almost an impossibility.

The evening finishes, as always at an Ailey performance, with Ailey’s Revelations, to ten gospel numbers (pictured left and top). That the dancers perform this with all their souls, without any sense that this is a chore to be waded through, is astonishing, yet a miracle they repeat every night. Revelations is, as always, a joy, and permits the sighting of a number of new talents, as well as a welcome return to more established stars. Akua Noni Parker and Amos J Machanic, Jr, in “Fix Me, Jesus” make a wonderful new partnership: Machanic is always a pleasure to watch, and Parker, with a classical ballet background, as well as having a lovely line, brings great dignity to the role – her deep, lush arm movements, from the very depth of her spine, are thrilling, like a great bird opening to its full wing-span. The three virtuoso men in “Sinner Man” – Jermaine Terry, Yannick Lebrun and Michael Francis McBride – brought the house down; and one uncredited man in “Rocka My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham” made the hair rise on the back of my neck: it was not that he danced any better than anyone else, but just like Fred Astaire, he had that extra snap, that tiny, precise finish to each movement, that made looking at anyone else almost an impossibility.

AAADT is touring in Britain for a month after its Sadler's Wells season, a welcome opportunity.

- Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre is at Sadler's Wells until 25 September; then at Nottingham Royal Centre, 1-2 October; Birmingham Hippodrome, 5-6 October; Plymouth Theatre Royal, 8-9 October; Cardiff Wales Millennium Centre, 12-13 October; Bradford Alhambra, 15-16 October; Edinburgh Festival Theatre, 19-20 October; and Newcastle Theatre Royal, 22-23 October.

Add comment