Is David Bintley the one that got away, the wrong turning the Royal Ballet took in the early 1990s? I have long thought so, and watching their current triple bill, the feeling only grows. Bintley trained at the Royal Ballet School, graduated into Sadler’s Wells (now Birmingham Royal Ballet), and became house choreographer for the Royal in 1985.

Then, in 1993, he fled. Two years later he took over at BRB, and the man who should, probably, have steered Britain’s premiere classical company for the next quarter-century has instead quietly, and productively, guided their second, sister company in the Midlands.

All well and good, but Bintley could – should – have been a contender. His work for BRB has been sterling, some brilliant. But tucked away in Birmingham, he has had neither the resources that London would have given, nor, sadly, the wider critical esteem, the recognition that is due to this major talent from those outside his own art-form.

All well and good, but Bintley could – should – have been a contender. His work for BRB has been sterling, some brilliant. But tucked away in Birmingham, he has had neither the resources that London would have given, nor, sadly, the wider critical esteem, the recognition that is due to this major talent from those outside his own art-form.

And certainly this triple reinforces that view. E=mc2 (right, photo: Roy Smiljanic) tops the bill, and remains on repeated viewings a work of dazzling originality. Based on an examination of Einstein’s theory of relativity (no, really, stick with me, it’s great), Bintley breaks the equation down into its three component parts, "Energy", "Mass" and "Celeritas (speed of light)". The first movement, all pounding percussion and sharp angles, is Balanchinean in its attack and ferocity, but shattered into sweetness by the recurrence of petite batterie, an English, Ashtonian lightness; "Mass" is a heavy, lyrical interlude of triplets before the perpetuum mobile that is "Celeritas" is unleashed upon us. (There is a solo break, before "Celeritas", entitled "Manhattan Project", an attempt to show the devastation caused by the practical application of the theory, in the atom bombs that were dropped on Japan. It is best overlooked as quickly as possible.)

Tombeaux, the central work, was the final, unhappy ballet Bintley created for the Royal, and its elegiac, backwards-looking sense of ending is a personal as well as an artistic one. The music was conceived by William Walton as a homage to Hindemith; in turn, Bintley looks back to Ashton, and Momoko Hirata and Joseph Caley make the most of its romantic, drifting sense of regret.

Tombeaux, the central work, was the final, unhappy ballet Bintley created for the Royal, and its elegiac, backwards-looking sense of ending is a personal as well as an artistic one. The music was conceived by William Walton as a homage to Hindemith; in turn, Bintley looks back to Ashton, and Momoko Hirata and Joseph Caley make the most of its romantic, drifting sense of regret.

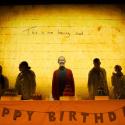

Still Life at the Penguin Café (left, photo: Bill Cooper) too is a monument to regret, to backwards-looking: to say it is the world’s only climate-change ballet is perhaps not to identify a very broad category, but it is an indication of Bintley’s breadth that these vignettes of doomed, extinct animals dancing at, in effect, the last-chance café, can flick in a moment from giddy charm to hopeless loss.

There were technical hitches on the first night (caused by not one, but two small fires in the rigging earlier in the day). But belatedly the show went on, and BRB’s dancers were looking particularly good: Joseph Caley in both E=mc2 and Tombeaux was in excellent form, as was Maureya Lebowitz in Celeritas, and Angela Paul in Penguin Café.

But to name specific dancers is invidious: the company, especially the corps in E=mc2, are at their best, and the programming is ideal – a quickfire shift between entertainment and intelligence, intellect and art. Lucky Birmingham.

Comments

Add comment