The Most Expensive Paintings Ever Sold

Leonardo's disputed Salvator Mundi has just topped the list. Who else is on it?

Yesterday the record for the most expensive painting ever sold was broken. At Christie's in New York Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi the hammer was knocked down on a price of $450 million. It's a lot of money, period, and even more for a painting which some doubt is by Leonardo at all. One doubter insists that Leonardo the great scientist would have refracted the light through the orb in Christ's hands. That won't bother the buyer, whose identity is unknown.

Salvator Mundi soars to the top of the list of the 75 most expensive paintings sold in the last 30 years. The recent Leonardo discovery was already on the list at no 19, having sold for $131.1 million in 2012. It now soars high above Willem De Kooning's Interchange ($300 million, sold 2015). Salvator Mundi is also the earliest work in the list. The newest is Jean-Michel Basquiat's Untitled, painted in 1982 ($110.5 million, 2017).

This list is based on prices at current values calculated by Wikipedia. It strays back three decades to the purchase of two Van Goghs. The big market surge came in 1989 when the record for an old master – Pontormo's Portrait of a Halberdier – was sold to the Getty Museum for what is now $68 million. The 1990s was a fallow decade in which only two painters could command high prices: Van Gogh (four entries) and Picasso (two). In 2006 the market suddenly rose for post-war work by De Kooning, Johns and Pollock. That year three paintings were sold for the equivalent of more than $160 million.

While paintings continued to go for eye-watering sums, the record held until 2011 when Cézanne’s The Card Players was sold for $259 million. The market has been at its most obscenely inflated in recent years. Seven of the top 75 sales happened in 2012, five in 2013, six in 2014, nine in 2015, five in 2016, and two this year (the other entry for 2017 is Roy Lichtenstein's Masterpiece.) The overwhelming majority of these works ended up in private hands.

The artists with the most entries hold few surprises. Picasso: 13. Van Gogh: eight. Warhol: seven. Rothko: six. De Kooning: four. Cézanne, Modigliani, Titian, Bacon: three. Johns, Monet, Lichtenstein, Klimt, Pollock, Newman: two.

Below is the list of the top, while the gallery overleaf shows some of the top 75, leading towards the most expensive in history.

- Leonardo da Vinci: Salvator Mundi - $131.1m, sold 2012 De Kooning: Interchange - $300m, sold 2015

- Gauguin: Nafea Faa Ipoipo (When Will You Marry?) - $300m, sold 2015

- Cézanne: The Card Players - $259m, sold 2011

- Pollock: Number 17A - $202m, sold 2015

- Rothko: No. 6 (Violet, Green and Red) - $188m, sold 2014

- Rembrandt: Pendant portraits of Maerten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit - $182m, sold 2015

- Picasso: Les Femmes d'Alger ("Version O") - $181.2m, sold 2012

- Modigliani: Nu Couché - $172.2m, sold 2015

- Pollock: No. 5, 1948 - $166.3m, sold 2006

- De Kooning: Woman III - $163.4m, sold 2006

- Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I - $160.4m, sold 2006

- Picasso: Le Rêve - $159.4m, sold 2013

- Van Gogh: Portrait of Dr. Gachet - $151.2m, sold 1990

- Klimt: Adele Bloch-Bauer II - $150m, sold 2016

- Lichtenstein: Masterpiece - $150m, sold 2017

- Bacon: Three Studies of Lucian Freud - $146.4m, sold 2013

- Renoir: Bal du moulin de la Galette - $143.2m, sold 1990

- Picasso: Garçon à la pipe - $132.1m, sold 2004

- Munch: The Scream - $125.1m, sold 2012

- Modigliani: Reclining Nude With Blue Cushion - $123m, sold 2012

- Johns: Flag - $120.8m, sold 2010

- Picasso: Nude, Green Leaves and Bust - $116.9m, sold 2010

- Van Gogh: Portrait of Joseph Roulin - $115.9m, sold 1989

- Van Gogh: Irises - $113.6m, sold 1987

- Picasso: Dora Maar au Chat - $113.1m, sold 2006

- Warhol: Eight Elvises - $111.2m, sold 2008

- Basquiat: Untitled - $110.5m, sold 2017

- Newman: Anna's Light - $108.7m, sold 2013

- Warhol: Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) - $108.4m, sold 2013

- Van Gogh: Portrait de l'artiste sans barbe - $105.1m, sold 1998

- Cézanne: La Montagne Sainte-Victoire vue du bosquet du Château Noir - $103m, sold 2013

- Rubens: Massacre of the Innocents - $102.1m, sold 2002

- Lichtenstein: Nurse - $96.4m, sold 2016

- Bacon: Triptych, 1976 - $96m, sold 2008

- Picasso: Les Noces de Pierrette - $95.3m, sold 1905

- Johns: False Start - $95m, sold 2006

- Van Gogh: A Wheatfield with Cypresses - $94.5m, sold 1993

- Picasso: Yo, Picasso - $92.5m, sold 1989

- Warhol: Turquoise Marilyn - $92.4m, sold 2007

- Titian: Portrait of Alfonso d'Avalos, Marquis of Vasto, in Armour with a Page - $91.1m, sold 2003

- Rothko: Orange, Red, Yellow - $90.6m, sold 2012

- Monet: Le Bassin aux Nymphéas - $89.6m, 2008

- Cézanne: Rideau, Cruchon et Compotier - $87m, 1989

- Newman: Black Fire I - $85.1m, 2014

- Rothko: White Center (Yellow, Pink and Lavender on Rose) - $84.1m, 200

- Van Gogh: Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers - $83.6m, 1987

- Warhol: Triple Elvis - $82.9m, 2014

- Warhol: Green Car Crash (Green Burning Car I) - $82.8m, 2007

- Rothko: No 10 - $82.8, sold 2015

- Monet: Meule - $81.4m, sold 2016

- Bacon: Three Studies for a Portrait of John Edwards - $81.7m, 2014

- Holbein: Darmstadt Madonna - est. $80m, 2011

- Titian: Diana and Actaeon - $78.8m, 2009

- Picasso: Au Lapin Agile - $78.6m, 1989

- Eakins: The Gross Clinic - $78.5m, 2007

- Rothko: No 1 (Royal Red and Blue) - $78.4m, 2012

- Picasso: Acrobate et jeune arlequin - $78m, 1988

- Picasso: Femme aux bras croisés - $76.5m, 2000

- Modigliani: Nude Sitting on a Divan ("La Belle Romaine") $75.7m, 2010

- De Kooning: Police Gazette - $75.4m, 2006

- Titian: Diana and Callisto - $74.8m, 2012

- Twombly: Untitled (New York City) - $71.3m, 2015

- Picasso: Femme assise dans un jardin - $71.2m, 1999

- Van Gogh: Peasant Woman Against a Background of Wheat - $70.9m, 1997

- Twombly: Untitled - $70.4m, 2014

- Warhol: Four Marlons - $70.4m, 2014

- Qi Baishi: Eagle Standing on Pine Tree - $69.7, 2011

- Warhol: Men in Her Life - $69.6m, 2010

- Picasso: La Gommeuse - $68.2m, 2015

- Picasso: Buste de femme (Femme à la résille) - $68.1m, 2015

- Pontormo: Portrait of a Halberdier - $68m, 1989

- Van Gogh: L’Allée des Alyscamps - $67m, 2015

- De Kooning: Untitled XXV - $66.3m, 2016

- Rothko: Untitled - $67m, 2016

Overleaf: browse a gallery of the world's most expensive paintings

The show – which has deep tentacles into the University of Cambridge – looks at how richly religious imagery and home life interacted with each other, framing activities from getting up, eating, going about one’s business, avoiding everyday perils (e.g. rabid dogs) and going to bed, to landmark occasions such as marriage, birth and death (a home birth or a "good" death was, of course, an intensely spiritual experience). It also shows how ideals of domesticity helped shape ideas of spirituality, resulting in "homely" religious images that adults and children could readily identify with. The Master of the Osservanza’s small luminous painted triptych of the Birth of the Virgin, a suitable object for female devotion, shows us Mary’s aged mother Anna, propped up in a bed with a glorious golden counterpane (in a prosperous domestic interior) shortly after miraculously giving birth.

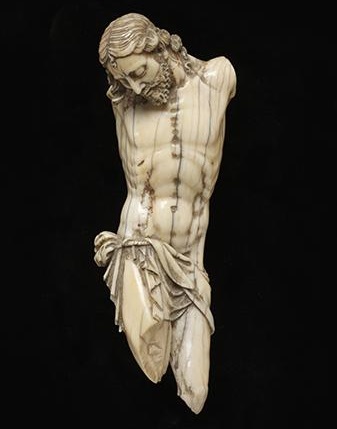

The show – which has deep tentacles into the University of Cambridge – looks at how richly religious imagery and home life interacted with each other, framing activities from getting up, eating, going about one’s business, avoiding everyday perils (e.g. rabid dogs) and going to bed, to landmark occasions such as marriage, birth and death (a home birth or a "good" death was, of course, an intensely spiritual experience). It also shows how ideals of domesticity helped shape ideas of spirituality, resulting in "homely" religious images that adults and children could readily identify with. The Master of the Osservanza’s small luminous painted triptych of the Birth of the Virgin, a suitable object for female devotion, shows us Mary’s aged mother Anna, propped up in a bed with a glorious golden counterpane (in a prosperous domestic interior) shortly after miraculously giving birth. The Fitzwilliam’s galleries have been broken up into small, richly coloured (forest green), Renaissance rooms with low-level lighting, so that the colours and materials of the paintings and objects really glow – to encourage prolonged looking. It works beautifully. Giovanni Antonio Gualterio’s ivory of Christ’s Corpus for a Crucifix , c.1599 (pictured)– which would be easily overlooked in its London "home" (amongst the treasures of the V&A in London) – is one of the highlights of the show. It succeeds (as it would as a treasured object in a private context) in inviting identification with Christ’s humanity and suffering and is intended, no doubt, to inspire love mingled with pain and acceptance.

The Fitzwilliam’s galleries have been broken up into small, richly coloured (forest green), Renaissance rooms with low-level lighting, so that the colours and materials of the paintings and objects really glow – to encourage prolonged looking. It works beautifully. Giovanni Antonio Gualterio’s ivory of Christ’s Corpus for a Crucifix , c.1599 (pictured)– which would be easily overlooked in its London "home" (amongst the treasures of the V&A in London) – is one of the highlights of the show. It succeeds (as it would as a treasured object in a private context) in inviting identification with Christ’s humanity and suffering and is intended, no doubt, to inspire love mingled with pain and acceptance. A more archaic Madonna and Child by Pietro de Niccolo da Orvieto (first half of 15th century) – with its painted marble back – also revealed by recent cleaning shows how such an image (part Byzantine icon/part Renaissance naturalism/part dream-like abstraction) would have been handled as an object, with the Virgin’s intense and benign gaze designed to meet the reverent gaze of the viewer, while the Christ child’s hand delicately touching his mother’s neck invites touching back. (Pictured above left: Studio of Sandro Botticelli, Virgin and Child, c.1480–90 © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge)

A more archaic Madonna and Child by Pietro de Niccolo da Orvieto (first half of 15th century) – with its painted marble back – also revealed by recent cleaning shows how such an image (part Byzantine icon/part Renaissance naturalism/part dream-like abstraction) would have been handled as an object, with the Virgin’s intense and benign gaze designed to meet the reverent gaze of the viewer, while the Christ child’s hand delicately touching his mother’s neck invites touching back. (Pictured above left: Studio of Sandro Botticelli, Virgin and Child, c.1480–90 © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge) As we make the journey through Hockney’s oeuvre – one that the artist has also clearly enjoyed revisiting – we move from his formative pictures as a student at the Royal College of Art in London, through to the breakthrough

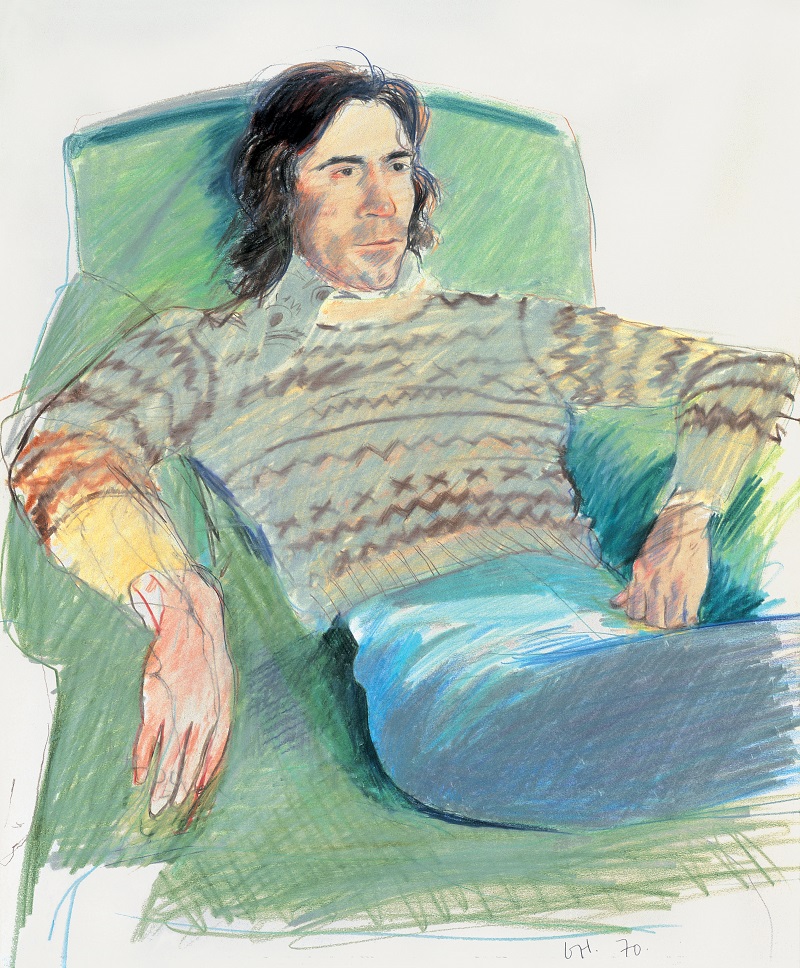

As we make the journey through Hockney’s oeuvre – one that the artist has also clearly enjoyed revisiting – we move from his formative pictures as a student at the Royal College of Art in London, through to the breakthrough  Hockney sees himself as a humanist: his reaction to the dominance of abstract art was to paint "pictures with people in": and not just any people. His sitters are usually friends, family or lovers. He came out early – while at college – deciding to embrace his homosexuality in his art; these paintings reflect his life and boyish humour, from escapades with early boyfriends to graffiti in the gent’s toilets. By being so constantly self-referential, Hockney became drawn to ambiguity, both in terms of the way we see the world, and the way the world sees us. (Pictured above right: Ossie Wearing a Fairisle Sweater, 1970. Private collection, London © David Hockney)

Hockney sees himself as a humanist: his reaction to the dominance of abstract art was to paint "pictures with people in": and not just any people. His sitters are usually friends, family or lovers. He came out early – while at college – deciding to embrace his homosexuality in his art; these paintings reflect his life and boyish humour, from escapades with early boyfriends to graffiti in the gent’s toilets. By being so constantly self-referential, Hockney became drawn to ambiguity, both in terms of the way we see the world, and the way the world sees us. (Pictured above right: Ossie Wearing a Fairisle Sweater, 1970. Private collection, London © David Hockney) Hockney’s interest in the human is intimately entwined with a feeling for the character of a place. The exhibition includes the winding hilly landscapes of his home in the Hollywood Hills (their fauvist colours capturing the dizzying journey to his Santa Monica studio) and the glowing landscapes of the Grand Canyon, followed by a contrasting room of Hockney’s expansive Yorkshire landscapes – selected from the many canvases that Hockney produced for his 2012 blockbuster at the

Hockney’s interest in the human is intimately entwined with a feeling for the character of a place. The exhibition includes the winding hilly landscapes of his home in the Hollywood Hills (their fauvist colours capturing the dizzying journey to his Santa Monica studio) and the glowing landscapes of the Grand Canyon, followed by a contrasting room of Hockney’s expansive Yorkshire landscapes – selected from the many canvases that Hockney produced for his 2012 blockbuster at the