The subtitle of Franz Osten’s 1928 film, A Romance of India, says it all: this Indian silent film is a tremendous watch, a revelation of screen energy and visual delight. An epic love story-cum-weepie with lashings of action and intrigue thrown in, it was an Indian-British-German coproduction (a curious strand of cinema history in itself) that was entirely filmed in India, and glories in having some of the country’s architectural wonders for locations: the Taj Mahal, central to the story, features primus inter pares.

German director Osten – he worked in India for close on two decades, making some of the classic films of the 1920s and 1930s, but never learnt an Indian language – also brings huge scale to its desert exteriors and crowd scenes, with hordes of camels, and a crucial elephant moment. It provided precedent for the Hindi post-war film industry as a whole, but there’s genuine feeling in the more intimate moments, as well as moments of realism that look forward even to the likes of Satyajit Ray’s classic Apu trilogy .

It all looks more than handsome in this BFI National Archive 4K restoration (there’s a short extra about that process), and the film’s new score from Anoushka Shankar is a treat. It must have been wonderful on the big screen with live ensemble when premiered as the LFF 2017 Archive Gala, but the combination of image and musical accompaniment certainly impresses from disc. Shankar has spoken of combining elements from the film’s 17th century historical setting, its 1920s production era and the present day, with the tastes of the latter dominating. As well as her own sitar – there are transcendent moments that sound so vibrantly alive, and gloriously lyric accompaniment for love scenes – she orchestrates for Indian bamboo flute and percussion elements, amplified at key moments by violin, cello, clarinet and keyboards.

It all looks more than handsome in this BFI National Archive 4K restoration (there’s a short extra about that process), and the film’s new score from Anoushka Shankar is a treat. It must have been wonderful on the big screen with live ensemble when premiered as the LFF 2017 Archive Gala, but the combination of image and musical accompaniment certainly impresses from disc. Shankar has spoken of combining elements from the film’s 17th century historical setting, its 1920s production era and the present day, with the tastes of the latter dominating. As well as her own sitar – there are transcendent moments that sound so vibrantly alive, and gloriously lyric accompaniment for love scenes – she orchestrates for Indian bamboo flute and percussion elements, amplified at key moments by violin, cello, clarinet and keyboards.

An early intertitle, “Love, Sorrow - and Fame Immortal”, gives a hint of the action. British scriptwriter WA Burton worked from a treatment of Niranjan Pal’s play about Mumtaz Mahal, consort of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, who commemorated her with Agra's monument to undying love (the Taj Mahal, pictured above). It’s a very free treatment of her life story, beginning with a childhood ambush that sees her brought up by a peasant family, her nobility unsuspected; they name her Selima and treat her as a sister to their son, Shiraz (the film’s producer Himansu Rai plays that role in adulthood, opposite the enchanting Enakshi Rama Rau). Kidnapped by slavers, she arrives in the Emperor’s harem, where the Shah woos her. But Shiraz will always love her: he follows her to the palace, where emotions run freely. His suffering is finally redeemed when, already blind, he enshrines her memory in the Taj Mahal: “not hands but the warmth of a heart built this which stands like a dream.”

The accompanying booklet essays throw fascinating light on the unusual circumstances behind the film, and the context of Indian film-making in the closing decades of the British Raj. Films were aimed simultaneously at the local and international markets (Shiraz was a hit in Europe, but not in the US). Documentary and propaganda was never far away, illustrated by two extras here: Temples of India is a 1938 10-minute travelogue, shot in colour by none other than Jack Cardiff. The 1944 12-minute Musical Instruments of India was a public information film to promote Indian arts and culture, interesting because it didn’t follow more standard wartime lines to emphasise instead the wider cultural achievements of the soon-to-be-independent nation.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Shiraz

It all looks more than handsome in this

It all looks more than handsome in this  The recurrent figure in Tavernier’s pantheon is Jean Gabin, the French acting icon from the 1930s through to the early 1960s, much more subtle than Depardieu in his depiction of the ordinary Frenchman. As Tavernier demonstrates with many carefully chosen clips, enhanced by an always eye-opening and thought-provoking commentary, Gabin was as fine an actor as any, not just the personification of a nation’s better self.

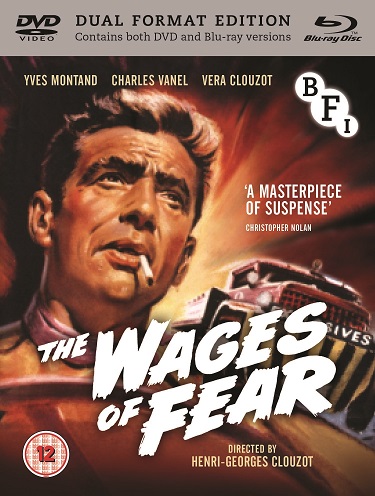

The recurrent figure in Tavernier’s pantheon is Jean Gabin, the French acting icon from the 1930s through to the early 1960s, much more subtle than Depardieu in his depiction of the ordinary Frenchman. As Tavernier demonstrates with many carefully chosen clips, enhanced by an always eye-opening and thought-provoking commentary, Gabin was as fine an actor as any, not just the personification of a nation’s better self. Yves Montand’s strutting Mario and Charles Varnel’s sly hard man Jo drive the first truck, followed by Peter van Eyck and Folco Lulli as Bimba and Luigi. What ensues is unbearably tense: who’d have imagined that a pair of slow-moving lorries could instil so much terror? Predictably, this isn’t an easy ride: bumpy roads, rock falls, and a pool filled with crude oil all play significant parts. The famous sequence where the trucks reverse onto a shaky wooden platform remains uniquely terrifying.

Yves Montand’s strutting Mario and Charles Varnel’s sly hard man Jo drive the first truck, followed by Peter van Eyck and Folco Lulli as Bimba and Luigi. What ensues is unbearably tense: who’d have imagined that a pair of slow-moving lorries could instil so much terror? Predictably, this isn’t an easy ride: bumpy roads, rock falls, and a pool filled with crude oil all play significant parts. The famous sequence where the trucks reverse onto a shaky wooden platform remains uniquely terrifying.