It was Benjamin Franklin who said "money has never made man happy...the more of it one has the more one wants," and there is no shortage of examples of boundless greed and how an abundance of cash can upturn and empty lives. Based on the memoir of Jordan Belfort, a former stockbroker convicted of fraud, The Wolf of Wall Street gives us one such example. This is Martin Scorsese's 23rd narrative feature and with it he proves that, at 71, he's inarguably still got it, with a flamboyantly immoral tale very much for and of our age, which is apparently the most effing foul-mouthed film in the history of cinema.

Scripted by Terence Winter, The Wolf of Wall Street sees Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) enter the weird world of Wall Street as an ambitious young pup with a devoted, darling hairdresser wife (Cristin Milioti). He's taken under the wing of a cawing, coked-up eagle played by (a show-stealing) Matthew McConaughey, who gives him some chest-beating musical mentorship over lunch in a scene to treasure. Unfortunately Belfort's timing couldn't be worse as he secures his broker's licence on 1987's Black Monday, and is immediately hoofed out of the firm. Showing that you just can't keep a greedy prick down, and with opportunities in the big league non-existent, Belfort turns his attention to penny stocks - applying his city slicker's nous to ruthlessly rinse those who can't afford to lose even small amounts, whilst teaching his "knucklehead" friends how to do the same. One of those, Donnie (Jonah Hill, pictured above), becomes his partner in crime; he's an obese lad with "phosphorescent" teeth, married to his first cousin ("if anyone's gonna fuck my cousin that's gonna be me"), who readily admits that it's likely that his kids will be retarded. Together they turn Stratton Oakmont into a billion-dollar brokerage firm - a law unto itself, staffed by barbarians - before the FBI come a-sniffing.

Showing that you just can't keep a greedy prick down, and with opportunities in the big league non-existent, Belfort turns his attention to penny stocks - applying his city slicker's nous to ruthlessly rinse those who can't afford to lose even small amounts, whilst teaching his "knucklehead" friends how to do the same. One of those, Donnie (Jonah Hill, pictured above), becomes his partner in crime; he's an obese lad with "phosphorescent" teeth, married to his first cousin ("if anyone's gonna fuck my cousin that's gonna be me"), who readily admits that it's likely that his kids will be retarded. Together they turn Stratton Oakmont into a billion-dollar brokerage firm - a law unto itself, staffed by barbarians - before the FBI come a-sniffing.

Scorsese has long dealt in anti-heroes, making great use of DiCaprio over the years, and there's an obvious comparison in the similarly biographical, comparably conveyed Goodfellas. But it's interesting to note the career of the film's screenwriter Terence Winter, who rose to prominence as writer / executive producer of The Sopranos and more recently as the creator of the marvellous Boardwalk Empire (there are cameos from several Boardwalk stalwarts). They are shows that lionise criminals but simultaneously show them as greatly troubled men, who suffer the consequences of their actions in terms of their business and in the damage that's inflicted on their psyche. Both make formidable use of the lengthier, more searching character development facilitated by TV as a medium.

As with Winter's previous work, the crooks take centre stage in The Wolf of Wall Street. However, rather than ramming home a moral, or painting a conflicting picture, the film instead drills home the screw-tomorrow excess, ultimately proving itself exhaustingly brash. It's told by a man living large, conscience-free, and who is thus obnoxious, unapologetic and chaotic. For instance, the untimely deaths of friends and colleagues are skirted over - Belfort doesn't want to dwell on that - and one marriage is quickly dealt a death blow (only vaguely felt) in order to usher another sucker in (Margot Robbie's glamorous Naomi, pictured below).

The Wolf of Wall Street is said to have outraged and appalled senior Academy members at recent awards screenings and it's a film which screams in your face that it's having fun, almost as if the filmmakers themselves are on something: Scorsese's pumped-up orchestration, Rodrigo Prieto's carnival-like visuals, Thelma Schoonmaker's energetic editing and Winter's potty-mouthed poetry fuse to form an appropriate evocation of a life cranked up to 11. It's a film that's huge amounts of fun, but there is a message in there: in the very hollowness, cruelty and precariousness of Belfort's existence, he's living a twisted version of the American dream, presenting a middle finger to both its people and the system, and it's just up to you whether to choose to see it. As the laughs and inebriated antics get wearing - and they do - you might notice that the lines on DiCaprio's baby face mirror the cracks in his marriage. Yet just one sequence bears the hallmarks of anything resembling conventional filmic morality - it's a punch in the gut, quite literally, wiping the smile off our faces and making clear our complicity in this act and all that's gone before. It comes as a shock and is almost more powerful for its isolation.

It's a film that's huge amounts of fun, but there is a message in there: in the very hollowness, cruelty and precariousness of Belfort's existence, he's living a twisted version of the American dream, presenting a middle finger to both its people and the system, and it's just up to you whether to choose to see it. As the laughs and inebriated antics get wearing - and they do - you might notice that the lines on DiCaprio's baby face mirror the cracks in his marriage. Yet just one sequence bears the hallmarks of anything resembling conventional filmic morality - it's a punch in the gut, quite literally, wiping the smile off our faces and making clear our complicity in this act and all that's gone before. It comes as a shock and is almost more powerful for its isolation.

The film's portrayal of women is, to be honest, pretty troubling. No doubt Scorsese and co are making a point about a world where women are routinely demeaned, or expected to accept the objectification of their gender (and by such mediocre men!) Despite this, it remains dispiriting that the film chooses to channel Belfort in this particular respect, reducing its most prominent female Naomi to nowt but a sex-pot, gold-digger, and reckless mother. Belfort might be no better than a reptile himself but, as played by an on-fire DiCaprio, he can at least be horribly charming and hilarious - a scene where he suffers the delayed effects of some very old prescription medication is likely to see off all-comers for the most hysterical sequence of 2014.

With appearances from Joanna Lumley and The Artist's Jean Dujardin providing the cherries on an already very overloaded knickerbocker glory, it's a feast of sorts. Scorsese and Winter have, quite deliberately, made a movie that for a long time is easy to chuckle at and guzzle down but, like its protagonist, is ultimately hard to like. But whether it's a begrudging or emphatic embrace, you just can't deny their chutzpah.

MORE MARTIN SCORSESE ON THEARTSDESK

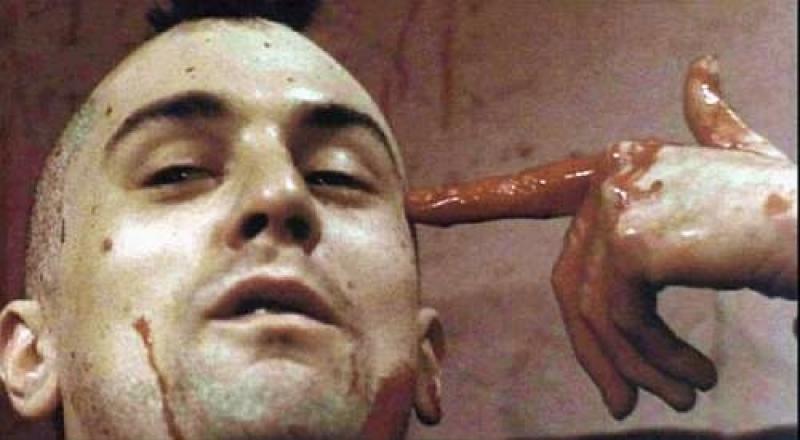

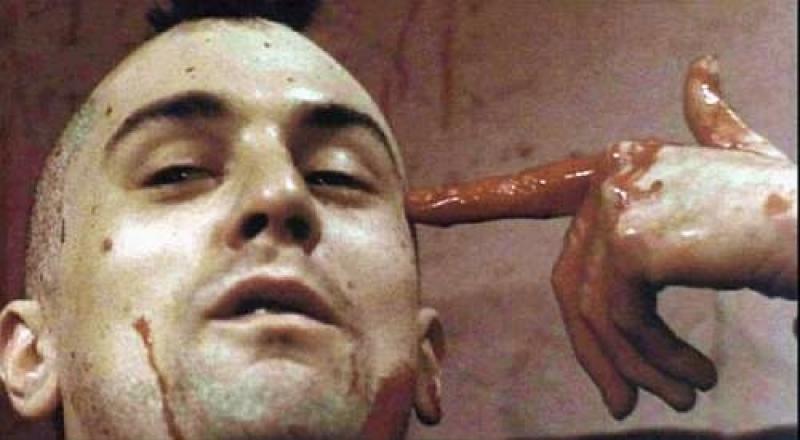

Taxi Driver (1976). Talking to me? Scorsese's classic starring Robert De Niro (pictured) is restored and re-released on its 35th anniversary

Taxi Driver (1976). Talking to me? Scorsese's classic starring Robert De Niro (pictured) is restored and re-released on its 35th anniversary

Shutter Island (2010). Not a blinder: Leonardo DiCaprio in Martin Scorsese's feverish paranoid thriller

Hugo (2011). Scorsese does a Spielberg in sumptuous look at the origins of cinema

George Harrison - Living in the Material World (2011). Martin Scorsese's epic documentary of the Quiet One

Arena: The 50 Year Argument (2014). A warmly engaging film about the 'New York Review of Books' might have been more than a birthday love-in

Vinyl (2016). Scorsese and Jagger's series is prone to warping, skipping and scratches

Silence (2016). Scorsese's latest is a mammoth, more ponderous than profound

Overleaf: watch the trailer for The Wolf of Wall Street

But that was only the start. In order to exploit his startling insight, Burry had to persuade the bankers to create the credit default swap, whereby he could bet large on the collapse of the US housing market. Since everybody had convinced themselves that the housing business, anchored on the personal investments of millions of honest Americans, could never go wrong, they were delighted to oblige.

But that was only the start. In order to exploit his startling insight, Burry had to persuade the bankers to create the credit default swap, whereby he could bet large on the collapse of the US housing market. Since everybody had convinced themselves that the housing business, anchored on the personal investments of millions of honest Americans, could never go wrong, they were delighted to oblige. That's just one of several devices the director shuffles to fend off glazed-eye syndrome. On-screen text might pop up helpfully, while spliced-in flashes of pop-culture imagery add a subliminal timeline. A deadpan sequence of how staid and boring banking used to be before the 1980s evokes a sleepy world of sludge-green and taupe, where bankers were mostly at lunch and two per cent was considered a handsome profit. The best trick is the unashamedly gratuitous introduction of celebrities to explain thorny plot points – "to tell you about subprime mortgages, here's Margot Robbie in a bubble-bath", or svelte popstrel Selena Gomez teaming up with economist Richard Thaler to give y'all the lowdown on "Synthetic CDOs".

That's just one of several devices the director shuffles to fend off glazed-eye syndrome. On-screen text might pop up helpfully, while spliced-in flashes of pop-culture imagery add a subliminal timeline. A deadpan sequence of how staid and boring banking used to be before the 1980s evokes a sleepy world of sludge-green and taupe, where bankers were mostly at lunch and two per cent was considered a handsome profit. The best trick is the unashamedly gratuitous introduction of celebrities to explain thorny plot points – "to tell you about subprime mortgages, here's Margot Robbie in a bubble-bath", or svelte popstrel Selena Gomez teaming up with economist Richard Thaler to give y'all the lowdown on "Synthetic CDOs". Showing that you just can't keep a greedy prick down, and with opportunities in the big league non-existent, Belfort turns his attention to penny stocks - applying his city slicker's nous to ruthlessly rinse those who can't afford to lose even small amounts, whilst teaching his "knucklehead" friends how to do the same. One of those, Donnie (

Showing that you just can't keep a greedy prick down, and with opportunities in the big league non-existent, Belfort turns his attention to penny stocks - applying his city slicker's nous to ruthlessly rinse those who can't afford to lose even small amounts, whilst teaching his "knucklehead" friends how to do the same. One of those, Donnie ( It's a film that's huge amounts of fun, but there is a message in there: in the very hollowness, cruelty and precariousness of Belfort's existence, he's living a twisted version of the American dream, presenting a middle finger to both its people and the system, and it's just up to you whether to choose to see it. As the laughs and inebriated antics get wearing - and they do - you might notice that the lines on DiCaprio's baby face mirror the cracks in his marriage. Yet just one sequence bears the hallmarks of anything resembling conventional filmic morality - it's a punch in the gut, quite literally, wiping the smile off our faces and making clear our complicity in this act and all that's gone before. It comes as a shock and is almost more powerful for its isolation.

It's a film that's huge amounts of fun, but there is a message in there: in the very hollowness, cruelty and precariousness of Belfort's existence, he's living a twisted version of the American dream, presenting a middle finger to both its people and the system, and it's just up to you whether to choose to see it. As the laughs and inebriated antics get wearing - and they do - you might notice that the lines on DiCaprio's baby face mirror the cracks in his marriage. Yet just one sequence bears the hallmarks of anything resembling conventional filmic morality - it's a punch in the gut, quite literally, wiping the smile off our faces and making clear our complicity in this act and all that's gone before. It comes as a shock and is almost more powerful for its isolation.