Under Western eyes, Gergiev’s Mariinsky forces had been turning to stone – like the titular shadowless woman's solipsistic husband in Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s polyphonic fairy tale – each time they stepped outside the Russian repertoire. There was the calamitous Verdi season at Covent Garden, and the ungainly Wagner Ring cycle which saw the opera company’s temporary twilight in London. In densest Strauss, the German word and the vital sense of movement arrived stillborn, but last night there were enough sparks in singing, playing and scenic vision to ignite swathes of this impossible epic.

Only an ensemble capable like Saint Petersburg's great ensemble of opulent work on all those three levels should even think of attempting what Strauss, who rather lost interest in his largest-scale opera during the difficult years of the First World War, called a "massive and artificial" project. We should be grateful for small mercies at the Mariinsky: Gergiev seems to have relinquished his half-baked directorial concepts in conjunction with the grandiose designer George Tsypin and called in a half-decent British director, the hit-and-miss Jonathan Kent, though his revival replacement, Lloyd Wood, can’t do much with all bar one of his singers. Struggling to be heard above the vast orchestra which portrays all the elements, as well as a heaven of sorts, versus a human hell are five principal roles as tough as anything in Wagner; you shouldn’t expect to hear them all equally well sung, but vocally the first of the Mariinsky’s two casts was actually up to the mark, though dramatically of very varying abilities.

All the characterisations demand huge stamina in a plot that’s less complicated than its mythic accoutrements might make it seem. There’s an airy-fairy heroic-tenor Emperor and his gazelle-into-porcelain-bride Empress, who through the mediations of a Machiavellian Nurse needs to acquire a shadow – in other words, fertility, though it would be charitable to think of it as the broader sort if Hofmannsthal’s odd scenario is not to be seen as a plea for the moral majority. To save hubby from petrification in three days’ time, she visits the hovel of a humble, placid dyer on earth, Barak, to snatch it from his discontented wife. But the Empress learns the compassionate lesson that you cannot buy your happiness at the price of a human being’s suffering.

The best narrative trick in Paul Brown’s imaginative but ultimately too widely strung design, and a real surprise, if you haven’t peeked at the production photos, is the first transition from Up There to Down Here – from a gauzy heaven of purples and reds, flowers, gateways and scudding clouds peopled by an Emperor based on Mughal hunting portraits and a ballgowned Empress to the garage home where Barak washes and dries his dyed fabrics in industrial-sized machines. For that first crucial interlude Gergiev whips up a phenomenal and dazzlingly textured orchestral storm, reminding us that Strauss by then knew Schoenberg’s Erwartung and would in turn inspire the Chinese gongs and percussion of Puccini’s Turandot, as Sven Ortel and Nina Dunn’s video and projection giddy us with their cloud colours (later, the essential falcon that first hunted down the Empress-gazelle multiplies and casts ever darker shadows as the nightmare reaches its apogee). Soon the music settles into a reverie of Schubertian simplicity for Barak’s goodness, rather over-urged by a grunting Gergiev but very beautiful on its own terms.

Something has probably been lost along the way of Tim Mitchell’s original lighting design. In reviving it for a different space, Sergei Lukin shows us that the Empress only has to stand by the machines to acquire her shadow; later, it’s staring her right in the face as it flickers over the rock-entombed Emperor while she hesitates over the crucial "yes" or "no" needed to get it. Fortunately it doesn’t matter too much because Mlada Khdoley is the most compelling actress on the stage, as pliant of body and beautiful of face as she is vocally near-ideal for the long Straussian lines of the composer’s most luminous heroine; you can hear the Four Last Songs already in this voice. Strauss sets up the greatest of the opera’s set pieces with a steady violin solo as the Empress faces the Solomonic judgment of her spirit-father Keikobad. Khudoley compels with her calm determination, and then scours our souls with the long passage of melodrama-shouting – extensively cut in every other production I’ve seen, not here – before the decision is ripped out of her like, as Hofmannsthal put it, the cry of a woman giving birth.

Khodoleyi, not Olga Sergeyeva as the trailer-trash wife with the beautiful soul, is the first lady of the evening, though you wouldn’t know it from the latter’s curtain call. Most Dyer’s Wives are a tad squally, and Sergeyeva’s is no exception, though good on her for doing a kind of Anna Nicole strip as she renounces her shadow before clinging to her purple teddy and deciding she wants it, and Barak, back. In a relationship which Hofmannsthal knew was a little like that between Strauss and his restless ex-singer wife Pauline – to be duly reflected in the marriage-opera Intermezzo which so amusingly echoes Die Frau – the placid husband needs more bass-baritonal evenness, and more suggestion of banked fires eventually erupting, than Edem Umerov can give him.

Viktor Lutsiuk’s Emperor is, like most heroic tenors, already half turned to stone at the start, and barely gets down the first scene’s staircase in one piece, but the fast-ageing voice is just about up to the mark; Gergiev and his Mariinsky cellos do most of the work in his big soliloquy. Most secure of all the voices is Olga Savova as the Nurse, capping the knee-trembling second act panoply of soprano/mezzo declamation, though alas she can neither move nor act, vital requirements in Hofmannsthal’s serpentine characterisation.

Movement is no strong point, in any case, of either Kent’s direction nor Denni Sayers’s hard to interpret choreography, a poor substitute for the stage directions of the Empress’s nightmare, so much more interesting to read in the libretto than to see on this stage. The bit parts are variable, the offstage voices too far away – blame the venue – and the kids in Act II jiggle around indeterminately as if in some amateur production. Kent needs to let his principals stand and deliver more downstage, and the dyer’s battered car that has to be pulled off and pushed on needs to go; a bicycle would do, though I see its point when it appears from an aerial perspective in Act III.

As the unborn babies finally twitter away and the couples celebrate their new-found fecundity in a protracted happy-end quartet Strauss just couldn’t believe in by 1918, Brown’s great ideas – the topsy-turvy view of earthly things pressing in from on high – go under in some banal scenic effects, and Gergiev, who does earth so much better than air, can’t paintbrush over the final cracks.

Yet once you leave the unsatisfying finale behind in your memory, the many amazing things about Strauss’s most comprehensive score, Hofmannsthal’s offbeat mythology and the way this mighty company goes about them crowd back in to haunt. Three cheers, then, that Scotland, which launched the best Rosenkavalier of recent years (David McVicar’s, now ensconced at English National Opera) as well as the most unexpected Strauss oddity beautifully done, Intermezzo, should now play exclusive festival host to flawed but enterprising genius in a work that won’t be coming around again too often.

OVERLEAF: MORE RICHARD STRAUSS ON THEARTSDESK

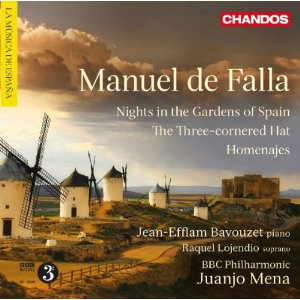

De Falla: Nights in the Gardens of Spain, The Three-Cornered Hat, Homenajes Jean-Efflaum Bavouzet (piano), Raquel Lojendio (soprano), BBC Philharmonic/Juanjo Mena (Chandos)

De Falla: Nights in the Gardens of Spain, The Three-Cornered Hat, Homenajes Jean-Efflaum Bavouzet (piano), Raquel Lojendio (soprano), BBC Philharmonic/Juanjo Mena (Chandos)