Only four flutes were on stage at the start of Jakub Hrůša’s latest concert with the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, the reins of which he took over from Jonathan Nott last September. Charles Ives would have been amazed to hear his “Voices of Druids” on the strings sounding, along with the solo trumpet, from the distance. I suddenly realised why Hrůša smiled enigmatically when I had asked him in interview the previous day whether he would segue straight from The Unanswered Question into Wagner’s Lohengrin Prelude (impossible without strings on the platform, of course). The idea was, in fact, to go immediately from Cage’s 4’33" of (nominal) silence in to Brahms’s Fourth Symphony in the second half, but reactions were different in each place the programme was played, and while in Schweinfurt there had been a near-riot, the Bamberg audience kept quiet and applauded enthusiastically before the Brahms could begin.

The unpredictables were clearly part of Hrůša’s brilliant programming In Bamberg's excellent concert hall (pictured right). But more brilliant still was his utterly discombobulating performance at the concert’s heart of Czech master Martinů’s unofficial Sixth Symphony, the Fantaisies Symphoniques of 1955 dedicated to the great Berlioz conductor Charles Munch. Here pinpoint detail was matched to gut-wrenching climaxes – much the deepest as well as best-articulated performance of the work I’ve heard, and that’s saying something since Hrůša’s teacher Jiří Bělohlávek would seem to own the work. It turns out, for reasons Hrůša gives below, that I could just as well have come to his first concert as official music director, featuring Mahler’s First Symphony, but here was confirmation of what we already knew from the eight operas he’s conducted at Glyndebourne, that a leading light among the younger generation of conductors – Hrůša is 35 – can now be numbered among the greats. I talked to him about Czech roots – the orchestra’s as well as his own – and how Mahler, as well as Martinů and Smetana, whose epic Má vlast he has just recorded with the orchestra (see Graham Rickson's review) is very much part of that picture.

The unpredictables were clearly part of Hrůša’s brilliant programming In Bamberg's excellent concert hall (pictured right). But more brilliant still was his utterly discombobulating performance at the concert’s heart of Czech master Martinů’s unofficial Sixth Symphony, the Fantaisies Symphoniques of 1955 dedicated to the great Berlioz conductor Charles Munch. Here pinpoint detail was matched to gut-wrenching climaxes – much the deepest as well as best-articulated performance of the work I’ve heard, and that’s saying something since Hrůša’s teacher Jiří Bělohlávek would seem to own the work. It turns out, for reasons Hrůša gives below, that I could just as well have come to his first concert as official music director, featuring Mahler’s First Symphony, but here was confirmation of what we already knew from the eight operas he’s conducted at Glyndebourne, that a leading light among the younger generation of conductors – Hrůša is 35 – can now be numbered among the greats. I talked to him about Czech roots – the orchestra’s as well as his own – and how Mahler, as well as Martinů and Smetana, whose epic Má vlast he has just recorded with the orchestra (see Graham Rickson's review) is very much part of that picture.

DAVID NICE The fascinating starting-point for me is that the Bamberg Orchestra was formed in 1946 from players in Prague’s German Theatre Orchestra, expelled after the war. For you is there still a Czech tradition or are you having to make it? Because I assume there are no Czech players here.

JAKUB HRUSA It's somewhere in the middle. There is a consciousness of the tradition in the institution, among the players and in the management, but as you say there's no Czech player, and there's a generational gap, and so I wouldn't say I have to build it anew, but it's like a substream of what the orchestra is. I would never say the Bamberg Symphony is a Czech orchestra, or a Bohemian orchestra, and I can compare with the Czech Philharmonic and all orchestras in my country which I have the honour to conduct. But it's true, on the other hand, that among German orchestras there is a clear affinity, if nothing else, in the first place, then in the relationship to Czech and Slavic repertoire here. You notice sometimes a certain superiority of German orchestras to maybe less well known Czech music. No-one has any questions about Dvořák, but anything else including Janáček, unlike in some other countries, is sometimes seen maybe as slightly inferior to the most important German traditions. I feel there has never been this feeling in Bamberg, not only because of the roots but because of the knowledge of that music, I think the orchestra played Czech music more than other German orchestras and therefore can evaluate its beauties.

I got to know and love the Martinů symphonies through the Bamberg recordings with Neeme Järvi, I don't know whether you can say there is anything like a Czech warmth about this orchestra, but it seems like a very warm sound, with especially beautiful wind playing.

I think so. The other day someone asked me about this Bohemian sound which is often mentioned in the media and public talks, and it's extremely difficult to verbalise – it's exactly that kind of phenomenon which is not meant to be verbalised, it's meant to be experienced.

But you're very aware of the sound.

I realised that what is called Bohemian sound is not a static acoustical phenomenon, but sound in terms of how a person creates sound in music, and I would involve this in what Bohemian sound means – the way of phrasing, the way of giving the music line, the warmth you mentioned, the common and very harmonious breathing and I always thought, after I got international experience, that what is somehow typical for Czech music-making, if I can at all analyse that feeling as I'm part of it, is a certain amount of intuition in playing music. And I think that differs a lot from Germanic traditions which tend to be much more aware of all the details of what one does. Whereas Czechs sometimes, and this has been criticised many times too, stop thinking about music and just give themselves to the current moment or inspiration, even if it's not most logical or rational. That's also true of composition, this is what distinguished Dvořák from Brahms, this tendency to be more intuitive and not controlling all possible aspects of music.

So that's just one aspect. I would not say the Bamberg Symphony is not controlling – they actually are German in the best sense of wanting to give structural aspects full attention, but at the same time there is this ability to relax into music in a way that is not occupied by brain all the time, and that's only possible when the spirit in the institution is harmonious, and when the community is friendly, that's the case here.

It's interesting when you talk about freedom in Dvořák. This is what one comes to expect most about Martinů (pictured left) – clearly he's very organised, but in works like the Fantaisies Symphoniques there is this seeming freedom, and people who want a logical sonata form are quite confused.

It's interesting when you talk about freedom in Dvořák. This is what one comes to expect most about Martinů (pictured left) – clearly he's very organised, but in works like the Fantaisies Symphoniques there is this seeming freedom, and people who want a logical sonata form are quite confused.

They protest, yes. It's interesting to observe that in every orchestra, ultimately Martinů's music works, if you do it with full passion and attention and if you choose pieces well – not every piece is on the top level, he was so prolific, I think that's a fate of all composers who were so prolific to produce some pieces better than others. But if you prepare the piece well and, as conductor at least, are fully convinced of what you do, in the end the orchestra is won over by Martinů. But there always remains a certain group of people either in the public or in the orchestra who say, it's great, it's fantastic music, but I still don't really understand what he's doing, in this place and this motif, it doesn't seem logical, things like that. And I tend to reply, well, maybe you appreciate the music most if you stop asking this way, if you accept it for what it is, a bit closer to life itself. It's like in life, you always see a certain logic, but then there are moments when the logic completely ceases to exist. And then I think the best recipe is just to accept it.

I took the eight-year-old son of a friend to a Prom to hear Stravinsky's Petrushka. The concerto was the Martinů Concerto for Two Pianos, and that was the piece that really caught his imagination. And I thought he would find it difficult. It struck me that a child questions less because every moment in great Martinů pieces can be alive, therefore you just accept it. Maybe the thing is to throw off all the baggage that you acquire as you get older.

Indeed, and I think it was his artistic credo, he felt this way of approach to art is more faithful to what art should bring to people's lives – that it probably shouldn't be so preoccupied with preconceptions and be a little bit freer in its fantasy, especially in his latest period, to which the Fantaisies Symphoniques belong, I think he tried intentionally to find a different component which makes the music hold together than the traditional form blocks, so to speak.

Which is why he called the work Fantaisies Symphoniques instead of Symphony No. 6

Actually, I make this mistake as well, calling it a symphony, although it has the seriousness and depth of a symphony.

You say you find some pieces weaker than others, but do you agree that the six symphonies, which are all written, the first five at least, in a short period of time later in his life, are all masterpieces?

They are all masterpieces, but nevertheless I have my favourites there, unlike in Brahms, where I cannot say which I prefer, or Dvořák's last four or even five symphonies – well, to be really accurate just the last three, I have a personal affinity to No. 6, I really love it. Five is the first which really grabs your attention fully. But it's true that it has certain weaknesses, but 7,8,9 – I cannot say which I love more, same for Brahms. In Martinů I have preferences.

For which ones?

I've recently done Five, and I cannot help but think that this symphony has a little bit less depth about it. I didn't say it's less interesting, but compared to Symphony No. 3, or 6, or the slow movement of Symphony No. 1, there I would completely agree with Charles Munch, who said that this slow movement is one of the most beautiful achievements of 20th century music. I just feel it goes deepest in searching for miracles in music, touches maybe briefly and in all its complexity some of the mysteries of what music can do.

You're from Brno, and Charles Mackerras always said you had to hear the Janáček Sinfonietta (Hrůša's listening guide for the Philharmonia above) played by the Brno Philharmonic to know what it should sound like. So that's a different sound to the Bohemian one – is Moravian culture different too?

Yes, I am a proud Brno native, but I don't read into it too much. It so much depends on who is conducting, what the constellation is, what quality of playing, etcetera. And there is too much of a false reliance on what is tradition, and so on. I would rather say what is more immediate in Brno, and I would guess that is still true, is that the relationship with Janáček is created more immediately. Not necessarily in these globalised times in the public, but the musical culture. Janáček is more strongly an integral part in the upbringing of musicians, the context of what it means to become a musician, and there Janáček is omnipresent and he's not seen as – of course, not as anything exotic, or from far and undesirable but something really from here. The institutions, obviously and thank God, tend to play Janacek more than elsewhere, there's a Janáček Festival. And I think in the opera they can, it's not only the Philharmonic, and now I'd like to talk about Janáček opera if I may...

Yes, please do.

It's now going through nice times. And there is a certain pure approach, without any additional stuff, if there's a good constellation of performers, you can breathe Janáček culture with more immediacy than elsewhere. But it goes so much with the care of the particular people who are in charge, and also if you look at the history of recordings, some are more, some less interesting – the truth is how Brno lived Janáček's music is valid and relevant, but we should be particular about it. Maybe that was what Sir Charles meant.

I think he particularly meant the sound of the trumpets, because the brass playing, when we travelled around Moravia, was ubiquitous in every place.

Actually that's right. You're right. Obviously Janáček in the Sinfonietta wanted an army band, and that says something about his concept of it – it shouldn't have been a cultivated, cultured, well-educated sound but something rougher. And it's true, the roughness, and also moving in a way, you're right, and I realised recently when I conducted Mahler's Third Sympony with the Bohuslav Martinů Orchestra in Zlin, which is a smaller town...

With the Bata shoe factory and amazing modernist architecture.

And there is a good concert hall now, it's actually in some ways the best concert hall in the country, if you don't count Prague's historical Rudolfinum and Municipal House and so on. And in Mahler, you also have these countryside village trumpets and all of a sudden I didn't need to describe what I wanted from those trumpets. If you take Mahler One, there's this funeral sound of the pair of trumpets, and it's this village funeral, and it's slightly ironic but also seriously meant, it's exactly some way in between, and it doesn't take any effort, actually it may be in some way a metaphor, to think that maybe that those players in the Mahler will go the next morning to play exactly at such a funeral, this connection between artificial music-making and village music-making is very strong. And so many of those brass players in Moravia simply play in the brass bands and at the balls and funerals and so on, and that distinguishes it for sure from the situation in London or Tokyo.

Jiří Bělohlávek liked to claim Mahler as a Czech composer – in a sense there is a Bohemian root there, isn't there, or a middle-Czech root...

Jiří Bělohlávek liked to claim Mahler as a Czech composer – in a sense there is a Bohemian root there, isn't there, or a middle-Czech root...

If we should be scrupulous we shouldn't say Czech, but he was Bohemian. I mean, geopolitically that is not a claim, it's a reality, but Czech is something else, Czech is connected with Czech language in terms of culture, and then Mahler was not at all. But Bohemian in connection with a country and cultural roots, and maybe some features of character and so on, although the Jewish part there is very strong, but this affinity to Czech lands, Bohemia, home of his birthplace Kaliště [the house pictured above] or Bohmia – that's valid.

Woods and fields and hills.

And it's actually very moving to realise that he was born extremely close to places where Smetana and Martinů were born, so he is a child of the same land. But of course culturally of a different stream, of that area which is exactly the background of the Bamberger Symphony, hence their somewhat very special natural relationship to Mahler's music, and therefore even if I was aware of amazing, fantastic achievements of the orchestra with Jonathan in the field of Mahler, I nevertheless chose Mahler One for my opening concert, because I thought – first of all, I think I am a profoundly different kind of conductor to Jonathan [Nott]...

How, would you say?

In a way I think it's quite clear, starting with the way we show with our arms, through our background and how we were educated in music, from where we come and stem, rehearsal style and general personality. It's just my guess, I've never met Jonathan, but I know him from his creations. So I thought I would like to experience this music which is so dear to the orchestra and me together. It would be a mistake, or I simply cannot imagine to avoid it because it has been played a lot, and it was truly a tremendous experience, everyone said it was different from what they used to play like, and yet another view of this beauty.

That has to be the backbone of any orchestra's repertoire, Mahler, along with Beethoven and Brahms.

But here especially I think it's really a visiting card of the orchestra if we are lucky enough, it really seems we are going to continue as the negotiations suggest, in exporting this abroad, because I think it's really a unique melting-pot, crossroads, culturally, where so many cultures meet – my presence here, this Czechness or Bohemianness or Moravianness comes even more into the play. I'm very much thinking lately culturally about streams of traditions and I realise more and more that it's almost impossible to insist on so much distinction within the central European region, because it was always very colourful in terms of shades and culture, and I really feel that the whole region, especially if you say Bavaria, Bohemia, Moravia, Austria, maybe a bit of Hungary too, Slovakia, lower part and maybe the very north of Italy, there's this what used to be, more or less with the exception of Bavaria Austro-Hungary, that really seems like a genuine whole of one culture with various shades.

Hungary seems to me a place apart – it's much more raw.

Probably, yes. But in some way when you compare folk music of eastern Moravia with folk music of north-western Hungary and that corner of Slovakia, it seems very close.

I'd say that was different from Bohemia and Austria.

But nevertheless I think even if you just follow the musical careers of people like Mahler, Budapest would always have been somehow included.

Next page: on studies with Jiří Bělohlávek, other great Czech conductors and the quiet of Bamberg

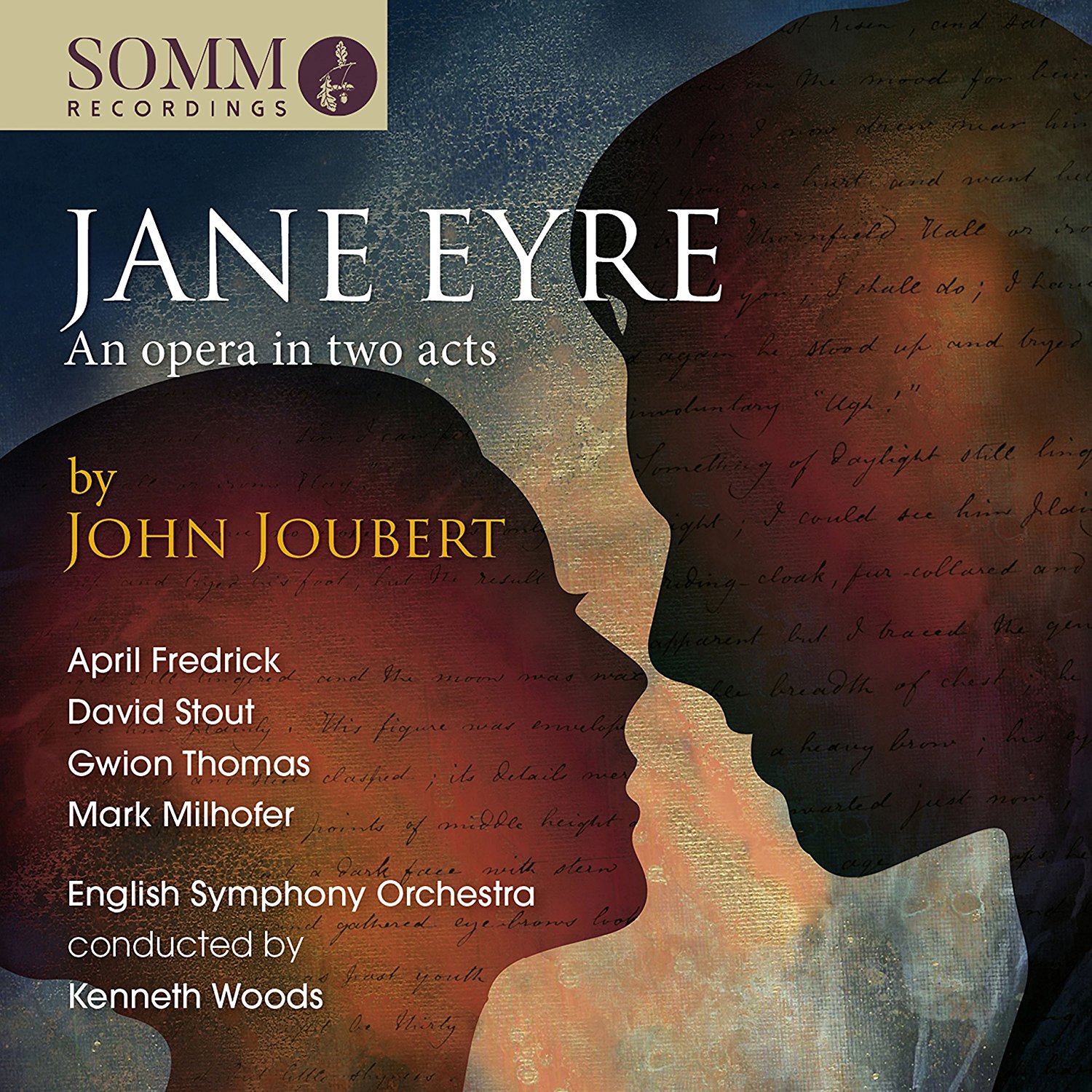

John Joubert: Jane Eyre April Frederick, David Stout, English Symphony Orchestra/Kenneth Woods (Somm)

John Joubert: Jane Eyre April Frederick, David Stout, English Symphony Orchestra/Kenneth Woods (Somm)

I think actually

I think actually  The unpredictables were clearly part of

The unpredictables were clearly part of  It's interesting when you talk about freedom in

It's interesting when you talk about freedom in  Jiří Bělohlávek

Jiří Bělohlávek