Debuting last February at the height of the economic crisis, Jonathan Miller’s freshly minted Bohème was a timely operatic glance in the social mirror. Almost two years on, and the hardships of his young Bohemians seem no less apt. With fiscal collapse so conveniently on the horizon, a lesser director might have succumbed and offered up a “relevant” contemporary treatment. It is to Miller’s credit (and one in the eye to those critics who so routinely deplore his smugness) that he not only avoided this dramatic dead end, but eschewed the self-conscious cleverness of Così or Rigoletto, instead delivering an understated, unobtrusive, 1930s Bohème that decorously whispers, rather than screams, “classic”.

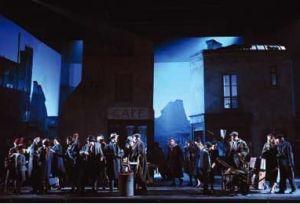

Wearing its Depression-era lightly, Isabella Bywater’s muted palette and mobile set lends a rare unity to the opera’s four acts, so often plunged from dusty penury to glaring technicolour for the Café Momus episode of Act Two. Her patrons are festive, her children freshly scrubbed, but there is none of the twee jollity that haunts John Copley’s production up the road (and only a gesture of a snowfall). By the same token her Bohemians, neither threadbare destitutes nor artistically dishevelled posturers, are merely scruffy and collectively in need of a hairbrush.

Revolving neatly to reveal Café and Inn, the set’s multiple levels place its young artists in a first-floor garret, greatly assisting the singers with the not inconsiderable issue of projecting over the enthusiastic orchestra. The upper storey did further service during Act Three’s charged confrontation between Mimi and Rodolfo. A lit window and gauzy curtain revealed the semi-clad figures of Marcello and Musetta, reconciling and fighting in the openly physical, explicit way that their counterparts fail – at such glorious musical length – to achieve.

With Broadway darling Alfie Boe returning to sing Rodolfo for just a handful of performances in January, the role is currently occupied by the magnificent Gwyn Hughes Jones. Matching a voice of crooning roundedness on the stave with all-out power above it, his Pinkerton woes were wiped clean within moments. There was no hint of tightness or tension through a performance whose puppyish vulnerability was a surprising bonus on top of such vocal authority. “Che gelida manina” neither lingered nor indulged, but poured naturally out. Perhaps the real high point however was the Act Four duet “O Mimi, tu piu non torni”, where, egged on by Roland Wood’s resonant baritone, he was finally able to release his full lyric force.

Supported by Wood (whose Act Four fandango was so enthusiastic as to risk the health of Bywater’s elegant set) along with George von Bergen’s beautifully sung Schaunard, an inspired cockney turn from Simon Butteriss (Benoit) and a rather woollier Colline from Pauls Putnins, the energy between the friends was relaxed and believable. In-jokes, pranks and baguette-duelling added much to the charm of the opening act, offsetting the opera’s lingering decline with gentle pathos.

Fresh from victory in last year’s inaugural Voice of Black Opera Competition, and making her ENO debut, was Elizabeth Llewellyn as Mimi. A spinto soprano of unusually dark tone, her covered sound and vowels are not at their best against the ringing brightness of Jones’s Rodolfo. Although unquestionably possessed of both the power and range for the role, her Mimi as yet remains something of a cipher, failing to articulate the arc between gentle coquette and maligned innocent that she must tread. Balanced for tone by Mairead Buicke’s solid Musetta, the vocal laurels for the evening were definitely with the men, and it was hard not to long for a return of 2009’s Melody Moore and Hanan Alattar to match them.

After a promising dervish of a start from the pit, Stephen Lord and his musicians settled into a colourful, if occasionally less than sprightly, rendition. Thwarted on more than one occasion by singers declining to linger, doubtless the pace and tone of proceedings will settle into unity as the run continues.

Neither chocolate box nor squalid bedsit, Miller’s production makes nuanced sense of what can so easily become an opera of primary colours. With a strong ensemble cast, poised orchestral playing and no mawkish excesses of sentiment, this is a Bohème for people who hate Bohème. For those who love it, it’s a treat.

- La Bohème is at the Coliseum until 27 January, 2011

- See what's on at English National Opera this season

Comments

Add comment