Oh boy. More Schubert. Deep breath. I had flashbacks of last month's wall-to-wall Franzi on BBC Radio Three. Nothing's come closer to ending my lifelong love affair with the tubby Austrian than the endless stream of half-finished three-part drinking songs that seemed to become the mainstay of that week-long celebration. Thankfully, last night at the Royal Festival Hall, we weren't getting any old Schubert. We were getting the great final trio of piano sonatas. And it wasn't just any old pianist performing them. It was Mitsuko Uchida. Who better to rekindle my feelings for the composer than the pianist who was recently given the Building a Library seal of approval for her recording of D960.

Unlike Beethoven's final three, Schubert's last piano sonatas aren't often played at one sitting. They're too long, too harrowing, too technically taxing for most to attempt in one go. And as a set, they don't offer the familiar emotional arc of a normal concert. Each one feels like an epic and an end. Each one seems to say as much as anyone can bear to take in a single concert. And then we have to prepare ourselves for more. More epileptic fits. More hallucinations. More mania and delusion.

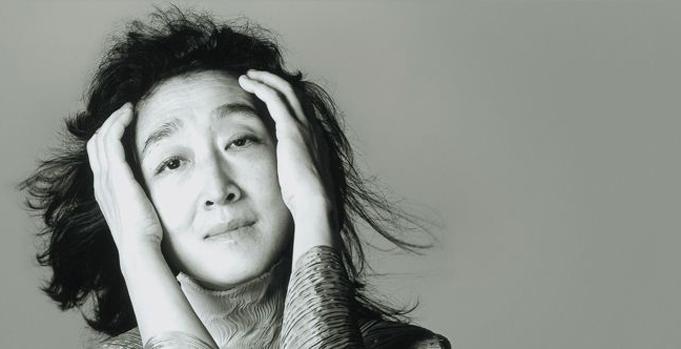

Her playing became wilder, more extreme, more intensely direct

But there are advantages to performing them as a set. One, the pianist has time to grow into them. Each breakdown can inform the next. Each textural encounter can be refined. Most importantly, the performer can increasingly let go. This last fact was very noticeable with Uchida. The first sonata, D958, was played with immense skill and polish. There was some beautiful voicing in the opening movement and Adagio, loving detail in the trio and brilliant impishness in the final Allegro. But apart from some punchy sforzandos in the dynamically terraced Adagio, politeness reigned.

The test of whether she was willing to let go would come in the Andantino of D959. And she passed with flying colours, breaking free of the tormented rocking with a torrent of keyboard abuse that Henry Cowell would have been proud of. One of her most effective musical tools throughout the evening was her rubato. Never was it better deployed than in her sculpting of this hellish terrain. But it also came into good use at the close of the sonata where the music begins to emotionally repair itself. The final chords were as deliriously joyous as the Andantino was bleak.

Her playing was becoming wilder, more extreme, more intensely direct. Her low trills in the first movement of D960 resonated with the viscera. In the second, all this torment and extremity was placed under a foggy veil. It was the most hypnotic part of the evening. The shift from minor to major in the recapitulation felt like the discovery of a holy inner sanctuary. A place I think few of us in the audience wanted to leave. But then we did leave and entered a Scherzo where there was if anything even more to delight: a spritely, child-like scampering that was Mozartian in its clarity and magic.

Then the bells of the Rondo began to toll. The evening was coming to an end. But not before some spectral apparitions wafted up through the purposeful tread of the opening statement. Heaven and hell make their appearances but fail to spirit away their victim. This is a sonata that ultimately rejects extremes for the rough and tumble of daily life. Uchida threw herself at this thought in the coda and, like a kid chasing a football, hurtled up and down the keyboard with an infectious and honest ebullience that quickly spread to the audience.

Comments

Add comment