“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from a troubled dream, he found himself transformed in his bed into a monstrous insect.” In one of the most famous opening lines in literature, Franz Kafka gives birth to a startling hallucinogenic premise. And Arthur Pita’s very clever dance drama produces something of a similar jolt in its precision and strangeness.

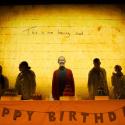

Simon Daw’s sparely elegant set presents the two halves of the Samsa household – on one side Gregor’s clinical white bedroom, looking like the “before” picture in a German Expressionist film of an insane asylum; on the other, the Samsas’ kitchen, an American 1950s white-on-white Happy Housewife extravaganza of clean lines, well-designed china and Waring blenders.

Mrs Samsa (the beautifully febrile Nina Goldman) and her ineffectual, out-of-work husband (a sympathetically louche Neil Reynolds) go through their daily routine: Gregor sets off for work, Grete, his sister, goes to school and hopes to become a dancer, they come home, eat supper, go to bed and begin again. Pita’s efficient and slick repetition of the departure, three times in a row, gives us Kafka’s sense of powerless futility, while Guy Hoare’s evocative lighting shades reality into phantasmagoria.

Mrs Samsa (the beautifully febrile Nina Goldman) and her ineffectual, out-of-work husband (a sympathetically louche Neil Reynolds) go through their daily routine: Gregor sets off for work, Grete, his sister, goes to school and hopes to become a dancer, they come home, eat supper, go to bed and begin again. Pita’s efficient and slick repetition of the departure, three times in a row, gives us Kafka’s sense of powerless futility, while Guy Hoare’s evocative lighting shades reality into phantasmagoria.

Dance is not particularly good at narrative, but it is wonderful at metaphor, and so Kafka’s extended fantasia of insectified life develops fluidly. The entire evening is predicated on the bizarre physical skills of Royal Ballet dancer Edward Watson, and his hyper-extended limbs, his extraordinarily flexible back and his virtually prehensile toes (which seem to have many more joints than most people’s) allow him to bend and twist into a series of contortions that display on his body Gregor's alienation of mind.

The insect seeps a black oil, which soon smears itself across the floor and walls, extended further by the incursion of a dream sequence involving three invading oiled black figures who besmirch Gregor further. The stains soon spread across the dividing line that separates Gregor’s room from the rest of the household, a symbol of the spreading poison of a vermin-infested house.

Grete (splendidly naively danced by Laura Day) is initially sympathetic to her much-loved brother, bringing him rotting food to eat and attempting helplessly to reach through his new carapace. While dance specializes in expressing relationships, family interaction has rarely been treated apart from the odd unpleasant fairytale stepmother, or the sympathetic or overbearing father. Gregor’s two pas de deux, with his sister and his fainting, panicking mother, are particularly touching, through his contorted body expressing straightforward expressions of gentle love and anxiety.

I do, however, have one major reservation. The lodgers that the family are forced to take in once Gregor’s salary is no longer forthcoming are, in Kafka’s story, “bearded”. They are not, however, in any other way marked out as any ethnicity or religion. In Pita’s rendition, they are very obviously orthodox Jews (klezmer music plays, in case we miss the point). Is there any particular reason for bringing in this sort of heavy stereotyping? Given Kafka’s own background, mistakenly referenced by Pita as Czech-language, despite Kafka’s origins as a German-speaking Jewish writer in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the fate of his family – two of his sisters died in the Łódź ghetto, the third in Auschwitz – I found myself deeply offended.

I do, however, have one major reservation. The lodgers that the family are forced to take in once Gregor’s salary is no longer forthcoming are, in Kafka’s story, “bearded”. They are not, however, in any other way marked out as any ethnicity or religion. In Pita’s rendition, they are very obviously orthodox Jews (klezmer music plays, in case we miss the point). Is there any particular reason for bringing in this sort of heavy stereotyping? Given Kafka’s own background, mistakenly referenced by Pita as Czech-language, despite Kafka’s origins as a German-speaking Jewish writer in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the fate of his family – two of his sisters died in the Łódź ghetto, the third in Auschwitz – I found myself deeply offended.

Watch The Metamorphosis trailer

Add comment