It’s shameful to admit it, but it’s perhaps rather surprising that a film about a fashion photographer and designer should end up being so profoundly moving and inspiring. Lisa Immordino Vreeland’s deft biopic about Cecil Beaton starts off dancing across the surface of his achievements – his iconic fashion images; his striking photographs of the royal family; his sumptuous designs for My Fair Lady, Gigi and other movies. But by the end, the director achieves a really rather remarkable portrait of a complex, cussed and equally remarkable man, one whose work continues to exert a profound influence on a later generation of artists (even if some, like photographer David Bailey, admit they couldn’t stand him).

Given the unconventional splendours of Beaton’s creations, Vreeland takes what feels like a rather disappointingly conventional, beginning-to-end perspective on his life, from cavorting with the Bright Young Things in the 1920s through to solitude and regret in his final years. But nevertheless, her structure feels as effortlessly elegant as one of Beaton’s own images, and she has a similarly fastidious eye for detail and nuance.

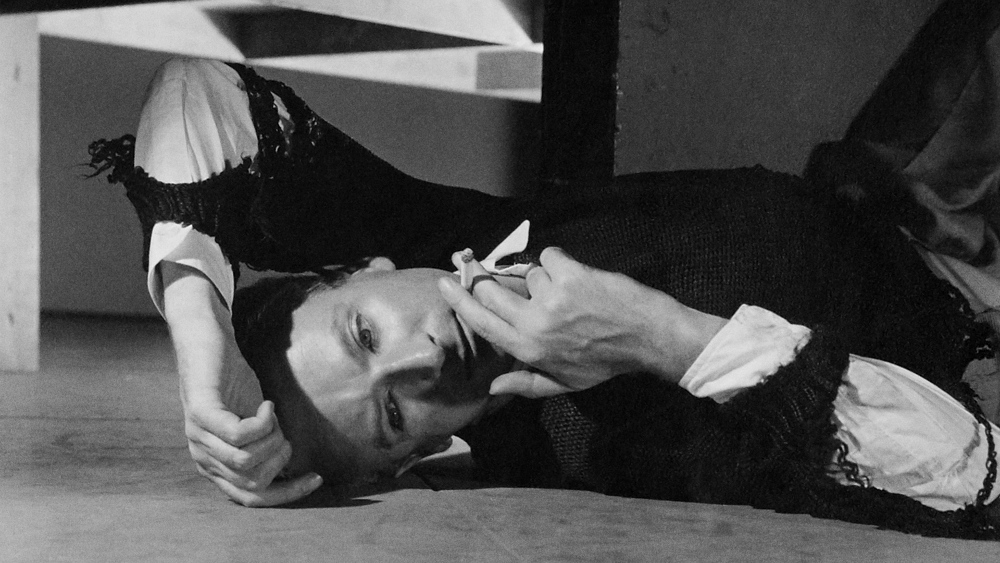

In between his youth and old age, we get to hear how Beaton (pictured below later in life, photo courtesy of the George Platt Lynes Estate) conquered America as photographer, illustrator and writer for Vogue, only to fall spectacularly from grace with an ill-judged "joke"; how he channelled his talents into unconventional (and often surprisingly erotic) documentary photography during the Second World War, restoring his reputation in the process; about his infatuation (and possibly fumble) with the reclusive Greta Garbo; and about his championing of the young David Hockney. There are valuable contributions from fashion designers Manolo Blahnik and Isaac Mizrahi, Sir Roy Strong and several other V&A figures, alongside purring extracts from Beaton’s diaries read by Rupert Everett, and Beaton’s own distinctive nasal drawl in disarmingly frank archive interviews. It occasionally feels as though Vreeland might be teetering towards hagiography, and yes, her tone is seldom less than adoring, if not downright reverential. But she’s careful, too, not to shy away from more difficult areas. Beaton’s sexuality, for a start. "I really am a terrible, terrible homosexualist, and I try so hard not to be," Beaton writes sadly in one diary entry, and he led a life of failed affairs and casual betrayal, covered with honesty and compassion here.

It occasionally feels as though Vreeland might be teetering towards hagiography, and yes, her tone is seldom less than adoring, if not downright reverential. But she’s careful, too, not to shy away from more difficult areas. Beaton’s sexuality, for a start. "I really am a terrible, terrible homosexualist, and I try so hard not to be," Beaton writes sadly in one diary entry, and he led a life of failed affairs and casual betrayal, covered with honesty and compassion here.

Or his shameless social climbing. Or his bitchiness. "I can hate unreasonably," he confides rather gleefully in an interview, and he’s right – going on to list the figures he particularly despises (Evelyn Waugh, Noël Coward, Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Katherine Hepburn for starters), often with precious little cause. It’s a side to Beaton’s character – both entertaining and appalling – that simmers away in the background throughout the film, but one that Vreeland is too polite to dwell on for too long.

In the end, however, Love Cecil isn’t just a celebration of Beaton’s seemingly miraculous achievements – despite his apparently endless portraits of everyone from Gertrude Stein to Daphne du Maurier, Truman Capote to the Queen, that slide gracefully across the screen. Even if Beaton’s life, as Vreeland concludes, was one of both melancholy and regret – a sadness at all he was unable to achieve, and at the enduring love he never found – it was also an unrelenting, inspirational quest for beauty and wonder in the everyday, The quiet tragedy for Beaton, however, was that that was never enough.

Comments

Add comment