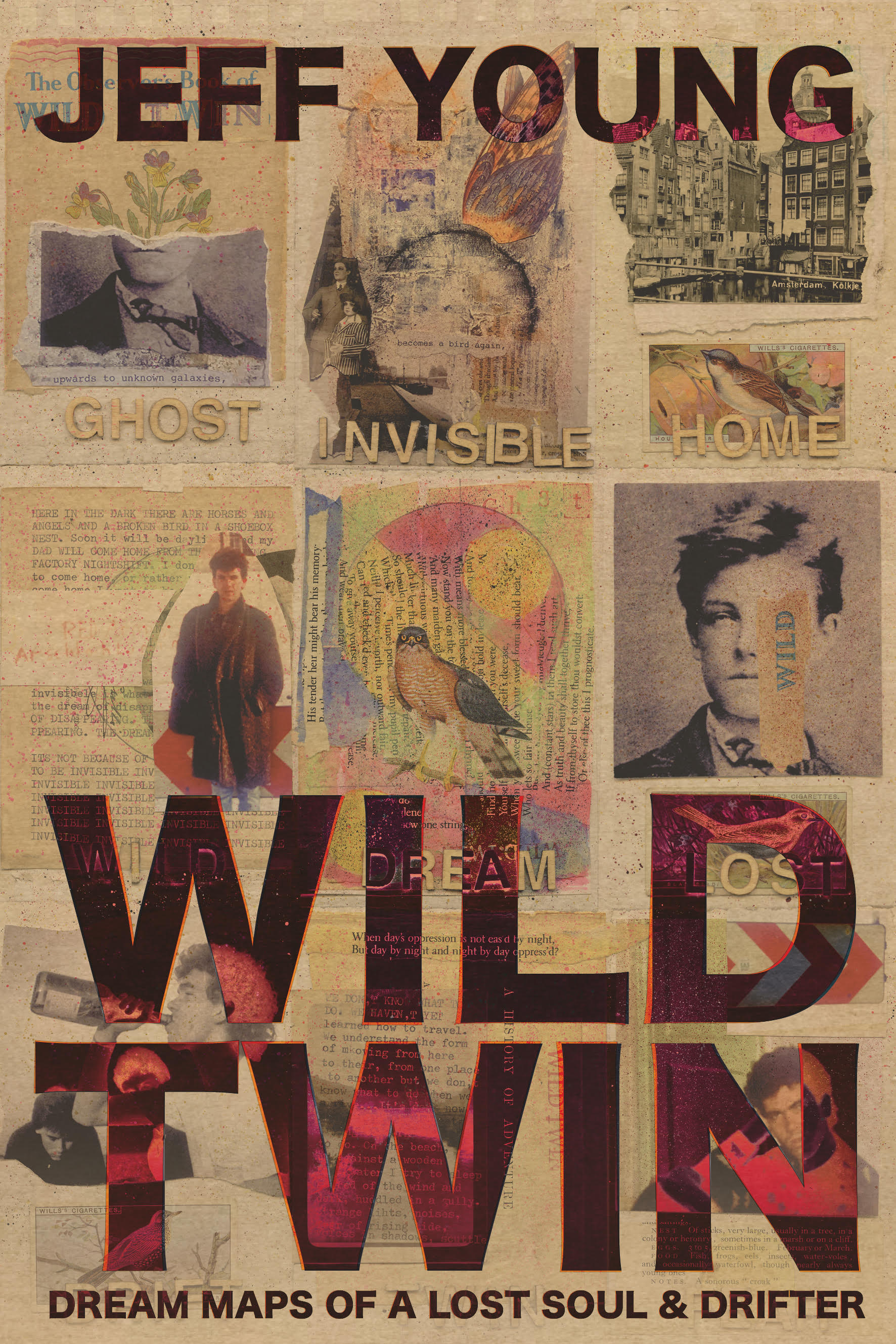

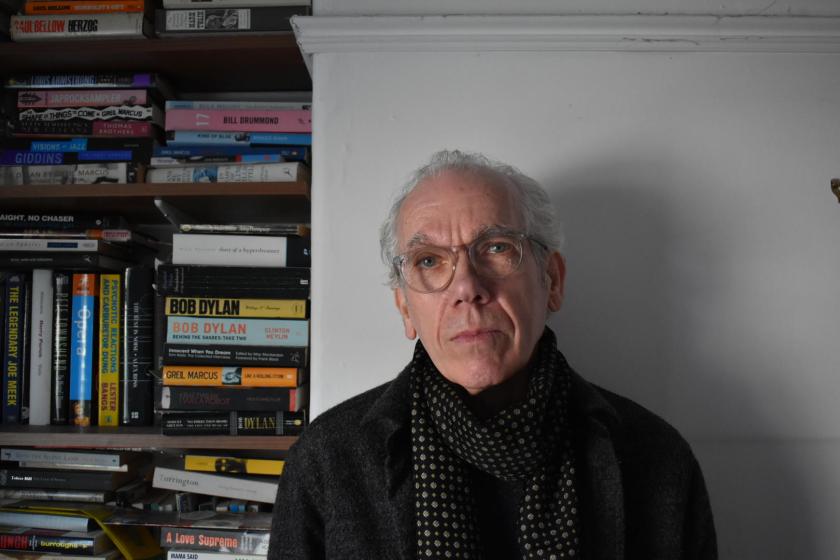

The writer, performer, and lecturer Jeff Young’s latest, Wild Twin, tells – ostensibly – the story of his barefoot, Beat-imitative journey through northern Europe in the 1980s. However, it is, at heart, a greater tale of his return, to family and to himself. Indeed, his account is perhaps more in tune with the work of Joseph Cornell, that strange artist of travel and nostalgia who never really left New York. Cornell would gather detritus, scraps, and ephemera from his native city and organise his findings into curious boxed collages, telling an oblique tale of inner journeying. Young makes such boxes, too; but, beyond this, we also find a literary style of scavenging as Young displays each episode of his life through discrete collection of stories assembled from dog-eared pages from his diary. Both capture an essential nostalgia in their creations, a yearning for something beyond themselves.

Born, raised, and (at first) trapped in a bureaucratic cul-de-sac in an exquisitely described Liverpool, Young devoured culture from a young age and yearned to be closer to what he feels is its source: Paris. He therefore strikes out for this mythical city (via Ostend), leaving his parents bereft, and so starts the first chapter of his history.

Attempting to make for France’s capital by hitchhiking, Young fails spectacularly for some time before reaching his object. The squalid conditions of his journey are heightened by filthy weather and odd run-ins with sympathetic strangers, as well as less sympathetic oddballs. Finally in Paris, Young is able to live out his dream for a brief moment, soon returning home, absolutely penniless. Before long, Young sets out again, this time for a more prolonged stay in a crumbling, almost magic-realist Amsterdam that has more than a flavour of Wim Wender’s Wings of Desire. This is an Amsterdam that has yet to fully recover from the blows and privations of the 20th century, populated by eccentrics like the junkie Chet Baker, and the washed up almost-Beat, Gregory Corso.

Attempting to make for France’s capital by hitchhiking, Young fails spectacularly for some time before reaching his object. The squalid conditions of his journey are heightened by filthy weather and odd run-ins with sympathetic strangers, as well as less sympathetic oddballs. Finally in Paris, Young is able to live out his dream for a brief moment, soon returning home, absolutely penniless. Before long, Young sets out again, this time for a more prolonged stay in a crumbling, almost magic-realist Amsterdam that has more than a flavour of Wim Wender’s Wings of Desire. This is an Amsterdam that has yet to fully recover from the blows and privations of the 20th century, populated by eccentrics like the junkie Chet Baker, and the washed up almost-Beat, Gregory Corso.

Young describes how he lived in an unstable squat with his partner at the time, which at one point was invaded by hordes of mice. He bounces from tenuous employment to even more tenuous employment, a career marked by illegality and theft. When it all finally blows up in riots across the city and he retreats across the channel, Young marks the beginning of a shift into a modernised, sanitised Europe. This is what he does so well: reviving the spirits and eventual decline of footloose vagabonds in these crumbling Northern European cities. There’s Rimbaud, the Situationists, Jazz junkies, and the Beats; but he never lets it feel too clichéd, which is a very possible fate.

Again, Cornell-like, he approximates these various styles of living and writing, but does so always with persistent sensitivity. Lying in his flea-ridden Paris garret, he knowingly captures aspects of his literary forebears through surreal free-association: “Dreams arise from dust, through the window the sky is full of lovers, men and women dancing in the heavens […] Andromeda and the Milky Way – like my mum’s pyjamas – shimmer in the city-glow. Antoine Doinel, Truffaut’s truant, is running through the alleyways of shadowplay night.”

Young’s narrative is also relieved and cast into relief by the final section of his narrative, where his wild youth is contrasted with the decrepit, Alzheimer-ridden decline of his father. Here we see Young arranging his stories and his objects into his imitation Cornell boxes, trying to hold onto a fleeting, fleeing memory of the past. Indeed, throughout the narrative Young questions his own recollection of his life: “Here is an Amsterdam memory that might not even have happened. It’s impossible. It’s inconsequential. In another way, it’s stayed with me forever as if folded in my wallet long ago”. In the purgatory he spends with his father before he dies, we see the unpicking of the idea of the Wild Twin: that frequent misrepresentation we make of our own memories, moulding ourselves into the heroes of our own stories, the centre of our own narratives. Wild Twin shows us this contrast and these contradictions, but never heavily, only lightly, a thing alluded to but perhaps easily forgotten.

Add comment