Pema Tseden's final film Snow Leopard is a Chinese Tibetan-language drama that addresses wild animal preservation. It serves as a kind of allegory for the circumstances that preceded the 53-year-old director's death from a heart attack last year. In 2016, Tseden was hospitalised after being roughed up by police when trying to retrieve his luggage at Xining Caojiapu International Airport. A diabetic, he was unable to take his pills while being held by the police.

In the film, four guys from a local television station have been given a tip off about a snow leopard getting into a sheep pen and killing nine rams. To cover the story they head for Drigar, a remote Tibetan village in China’s Qinghai Province.

On arrival, they interview the herdsman (single-named actor Jinpa), who is beside himself with rage and intends to kill the snow leopard, now imprisoned in the pen, unless he receives compensation to the tune of 10,000 yuan. The trouble is that, as an endangered species, snow leopards are protected. Killing them is illegal.

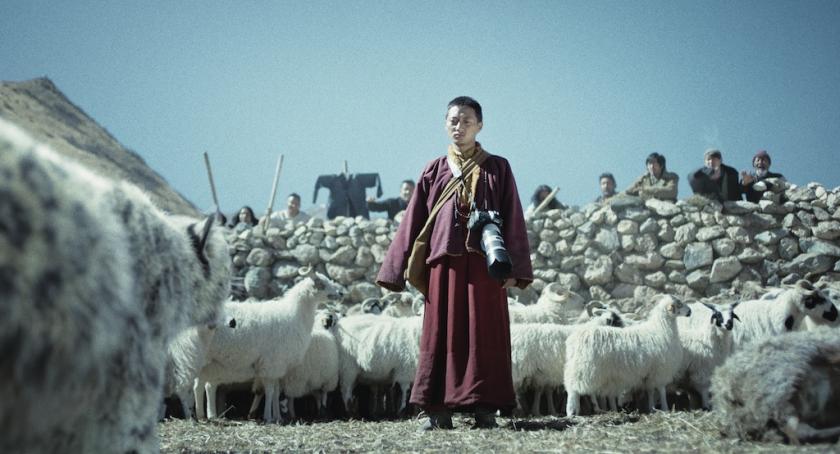

The herdsman’s younger brother (Tseten Tashi, pictured centre with Jinpa on right) is a trainee lama nicknamed the Snow Leopard Monk because he obsessively photographs these beautiful and elusive animals. When he climbs into the pen to confront the captive leopard, a surreal black and white sequence ensues. A dramatic flashback shows the snow leopard running amok among the sheep. CGI and clever editing make the hunt remarkably convincing; as the terrorised sheep try desperately to escape slaughter, their panic is palpable.

The herdsman’s younger brother (Tseten Tashi, pictured centre with Jinpa on right) is a trainee lama nicknamed the Snow Leopard Monk because he obsessively photographs these beautiful and elusive animals. When he climbs into the pen to confront the captive leopard, a surreal black and white sequence ensues. A dramatic flashback shows the snow leopard running amok among the sheep. CGI and clever editing make the hunt remarkably convincing; as the terrorised sheep try desperately to escape slaughter, their panic is palpable.

Sadly, though, all the other visual effects are clunky beyond measure. The monk fantasises releasing the leopard and, in an especially unlikely sequence, the animal repays this favour by rescuing him from the mountains and giving him a ride home. In close up, Tashi nestles his cheek against a snow leopard pelt as though he were lying on the animal's back; cut to long shots of a big cat running cross country with a small dark shape clinging to its back. Only the gullible would be taken in by this clumsy conceit.

Back in the village, government officials and then the police arrive to try to persuade the herdsman to free the big cat. The more they insist, though, the wilder and more violent he becomes.

While we learn the names of the Chinese televison crew, the TIbetan family remain nameless – nothing more than brother, father, sister-in-law etc. One might assume from this and from the portrayal of the herdsman as a ranting, bone-headed madman that the director is Chinese and that decisions like these are examples of Chinese arrogance. But, given that Tseden was a pioneering figure in Tibetan cinema, it makes one wonder who this film was intended for and what he was trying to say with it. Although the police on screen are not heavy handed, one can't help feeling that the story contains more than a hint of the director's own fateful run-in with law enforcement.

Add comment