Transcendence is everywhere in Mahler’s most ambitious symphony, from the flaming opening hymn to the upper reaches in the epic setting of Goethe’s Faust finale. You’d think no visuals could match the auditory phantasmagoria, just as dance, music and design flunked the essence of Paradiso in the Royal Ballet’s The Dante Project. Mahler does compose a kind of concert opera in Part Two, though; sound, movement and image accorded well.

The Southbank Centre has splashed out on its sound-and-vision Multitudes festival, which here meant further expense in a work that already calls for a large orchestra and eight soloists, some necessarily of Wagnerian stature (you don't have to pay the choirs, unless you beef them up with professionals, which always helps and might have added another incandescent turn of the screw). In addition we had six members on the video team, including the actor who played Faust onscreen and later on stage, and in addition to director Tom Morris, video artist Tal Rosner and lighting designer Ben Ormerod three more helpers of questionable necessity – 12 additions to the original, in all.  Part One, Mahler's impetuous and exultant setting of the Pentecostal Hymn to the creative spirit, might have done without the extras, though summaries of the text on the screens were a help; the images reminded me of the sci-fi posters I had on my wall as a teenager.

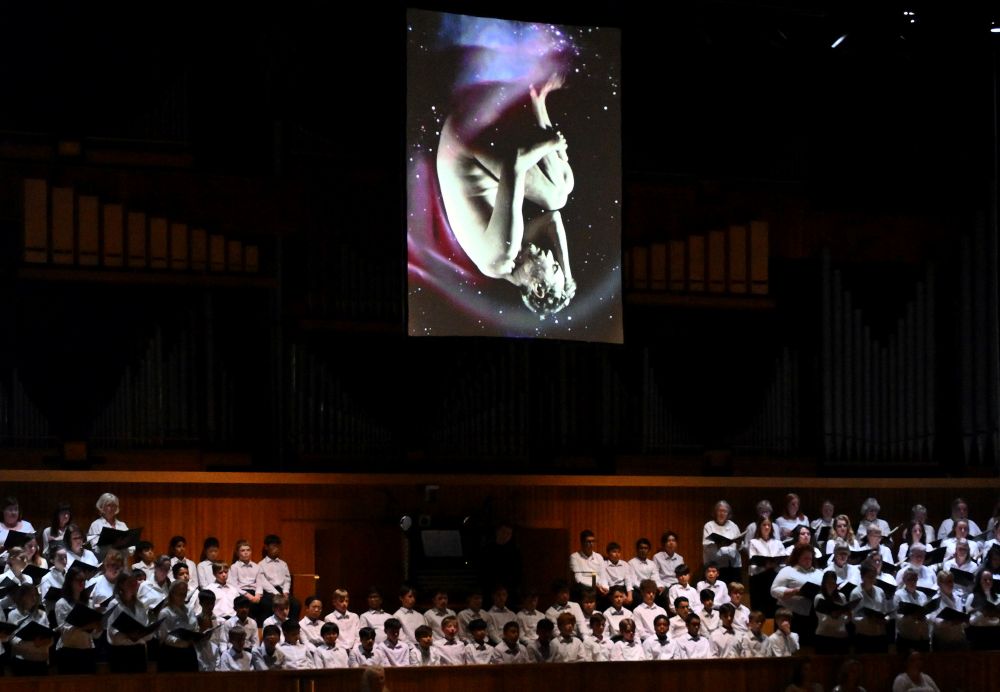

Part One, Mahler's impetuous and exultant setting of the Pentecostal Hymn to the creative spirit, might have done without the extras, though summaries of the text on the screens were a help; the images reminded me of the sci-fi posters I had on my wall as a teenager.

Nothing, at any rate was crass enough to obscure the clarity of Edward Gardner's vision: a brilliant opening blaze, men of the London Philharmonic Choir and London Symphony Chorus – still not over-large forces – fanning out into the auditorium like angel wings, then a saving-up of real fervour until the tumultuous flash of "Accende lumen sensibus" (pictured above), a grip on the polyphonic splendours and a real release in the cosmic ringing of the coda. Soloists with scores standing against the back wall of the platform acquitted themselves well enough for starters, more like a Verdi Requiem team multiplied, spotlit like the occasional orchestral soloist; the real tests were to come.

And in the Faust drama, they nearly all made as good a mark as they could, though more rehearsal time – is any really enough? – would have forged greater confidence as they took their various places, now off the score. I was surprised to find that the adequate baritone, first to enter in this Siegfried-like progress from the depths to the light, was Tommi Hakala, not sounding in best voice last night. Derek Welton (pictured left, the only soloist other than Hakala featured in the photo selection) outstipped him in the longer solo of the Pater Profundus.

And in the Faust drama, they nearly all made as good a mark as they could, though more rehearsal time – is any really enough? – would have forged greater confidence as they took their various places, now off the score. I was surprised to find that the adequate baritone, first to enter in this Siegfried-like progress from the depths to the light, was Tommi Hakala, not sounding in best voice last night. Derek Welton (pictured left, the only soloist other than Hakala featured in the photo selection) outstipped him in the longer solo of the Pater Profundus.

No character names or Mahler's quasi-stage directions – following in Berlioz's footsteps in creating a hybrid concert drama – were given on the screens, but Rosner now came into his own with the depiction of Faust's soul in the personage of Tristan Sturrock, frozen then gazing in wonder before revolving in foetal position as he ascended. Was this really the "nudity" that made the Southbank warn against the presence of children under 12? At any rate the Tiffin Boys' Choir was there, backs to the screen, making their cheeky mark as younger angels (pictured below with one of the Faust images), at one point cupping their hands to make a stronger point.

Andrew Staples, seemingly transformed from radiant one-time Tamino to Siegmund status, managed all his highest lines and notes without stress, an engaging presence. The female soloists were all good to great, Christine Rice prompting dramatic sympathy in the assemblage of the three once-earthly souls, Jennifer Johnston unfurling the richest sound up to that point. She was matched by Emma Bell, never better, as the sympathetic Gretchen pleading for Christ's soul.  And it was from that point on that the emotion became overwhelming, as it must with Mahler pulling out one celestial trump card after another. Gardner had the full measure of the protracted leaving-behind of earthly things to welcome the "eternal feminine". Jennifer France floated lines from on high in Marian blue, the chorus sank to awed magic, an emotional intensification of the same point in the "Resurrection" Symphony, building to an even more overwhelming climax, the brass choirs in the highest spaceship boxes to left and right reasserting the "Veni creator". How odd that so many people still have problems with this masterpiece; its symphonic unity is astounding across such a span, its ultimate goal achieved in a performance as fine as this.

And it was from that point on that the emotion became overwhelming, as it must with Mahler pulling out one celestial trump card after another. Gardner had the full measure of the protracted leaving-behind of earthly things to welcome the "eternal feminine". Jennifer France floated lines from on high in Marian blue, the chorus sank to awed magic, an emotional intensification of the same point in the "Resurrection" Symphony, building to an even more overwhelming climax, the brass choirs in the highest spaceship boxes to left and right reasserting the "Veni creator". How odd that so many people still have problems with this masterpiece; its symphonic unity is astounding across such a span, its ultimate goal achieved in a performance as fine as this.

Add comment