I first came across Rachel Jones in 2021 at the Hayward Gallery’s painting show Mixing it Up: Painting Today. I was blown away by the beauty of her huge oil pastels; rivulets of bright colour shimmied round one another in what seemed like a joyous celebration of pure abstraction.

Yet hidden within this glorious maelstrom of marks were brick-like shapes representing teeth; Jones is fascinated by mouths and the dentures that, literally and metaphorically, guard these entry points to our interior being.

The 34-year-old is the first living artist to show in the main exhibition space at the Dulwich Picture Gallery. Her reference point for the commission is a delightful painting of a hunting dog by 17th century Flemish painter Pieter Boel. Seen in profile, the dog looks up expectantly, its jowls hanging loose beneath its pointed muzzle – a mouth soft enough to retrieve dead game without harming the delicate flesh. By contrast, the mouths in Jones’ pictures are isolated from the rest of the face and are shown head on. The series Spliced Structures, 2019, features close-ups of luscious lips that often seem bruised yet, nonetheless, appear to be smiling. Drawn life-size on small canvas offcuts, they look fleshy, seductive and very vulnerable.

The 34-year-old is the first living artist to show in the main exhibition space at the Dulwich Picture Gallery. Her reference point for the commission is a delightful painting of a hunting dog by 17th century Flemish painter Pieter Boel. Seen in profile, the dog looks up expectantly, its jowls hanging loose beneath its pointed muzzle – a mouth soft enough to retrieve dead game without harming the delicate flesh. By contrast, the mouths in Jones’ pictures are isolated from the rest of the face and are shown head on. The series Spliced Structures, 2019, features close-ups of luscious lips that often seem bruised yet, nonetheless, appear to be smiling. Drawn life-size on small canvas offcuts, they look fleshy, seductive and very vulnerable.

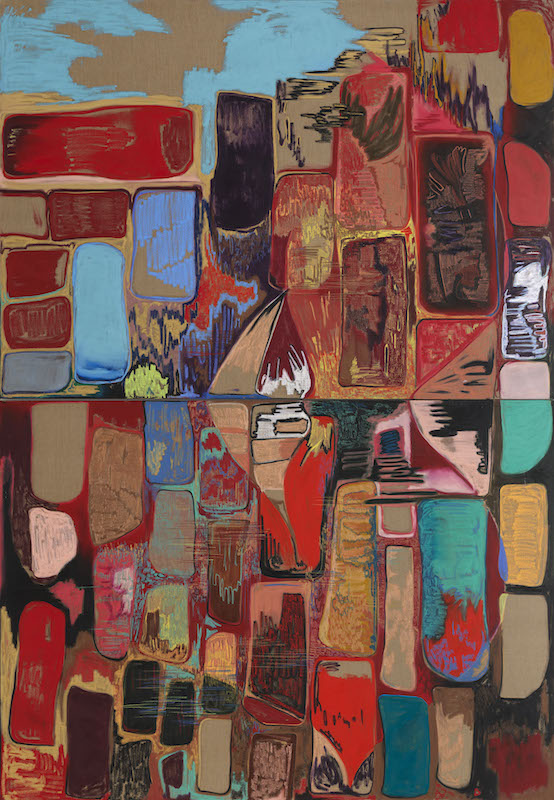

These little sketches are like an intimate preamble to the eight huge canvases that dominate the space, often featuring bared teeth so large they resemble tombstones or architectural structures (main picture: Gated Canyons). Yet they don’t seem threatening since, rather than snapping at one’s heals, they stand sentinel, barring one’s way to the mysterious portals. Some are accompanied by bricks (pictured above right) that create insurmountable barriers blocking one’s path.

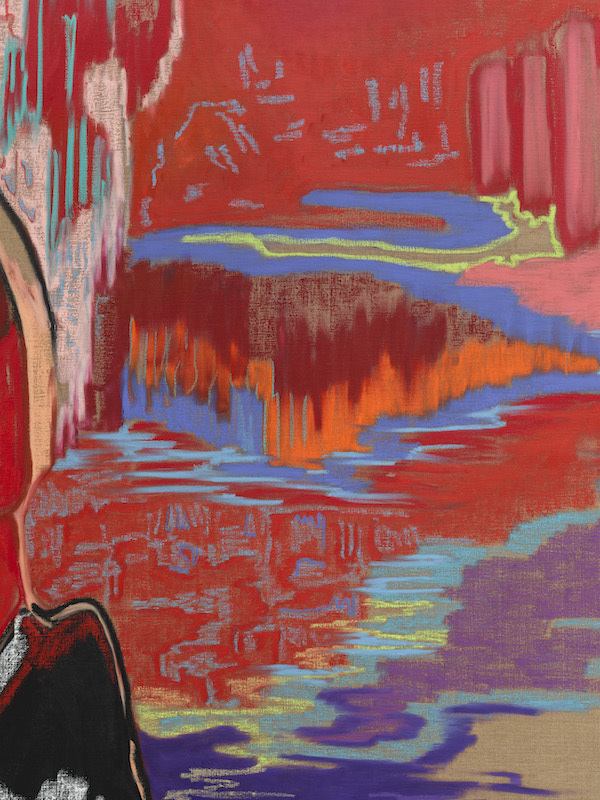

Surrounding the teeth are pools of psychedelic colour (pictured below left: Gated Canyons (detail)); complementary pairs – oranges and greens, purples and yellows, crimsons and turquoise – shimmer like reflections of sunlight on water or bleed into areas of raw linen whose dull brown is like the dark underbelly to these sizzling, rainbow scratchings.

Dominating the final room is a picture devoid of teeth. Dangling from a carnival cloud of jazzy yellows, blues and oranges is a huge, phallic tongue. Coloured blushing pink, rich purple and warm red, it is as shocking as the glimpse of a dog’s penis unsheathed from its protective folds of skin – fleshy, raw and pulsating with need.

Dominating the final room is a picture devoid of teeth. Dangling from a carnival cloud of jazzy yellows, blues and oranges is a huge, phallic tongue. Coloured blushing pink, rich purple and warm red, it is as shocking as the glimpse of a dog’s penis unsheathed from its protective folds of skin – fleshy, raw and pulsating with need.

The presence of such an overtly suggestive image feels like a confession – an acknowledgement of the fact that the mouths and their guardians harbour other layers of meaning. No wonder Jones’ pictures are such an orgy of sensual delight. It seems that they embody the pleasure principle and the many fears that accompany surrender to desire.

Add comment