"Bad Star Trek episodes" is how one director describes a certain unfortunate look in would-be intergalactic opera productions. The late Nikolaus Lehnhoff came perilously close to it in his Glyndebourne Tristan und Isolde but offered a coherent vision. Daniel Kramer, now ENO's Artistic Director, has a few "bad Star Trek episodes" and many good ideas that don't always join up or else outstay their welcome. Unevennness abounds: hideous costumes and makeup clash with Anish Kapoor's eventually brilliant designs, singing and conducting are only patchily inspired.

Let's celebrate the best first. Stuart Skelton's Tristan is the finest account of Wagner's most extreme and taxing operatic character - Brünnhilde and Wotan notwithstanding - that I've ever seen or heard on a stage (the ultimate assumption, Jon Vickers', was just before my time). He runs the gamut of sound from tenderness and near-extinction on a deathbed from which he can't or won't be released to full Heldentenor pelt in expectation of Isolde's arrival and even a dangerous but apt supra-singerly edge for the extremes of the endgame.

Two other singers amaze. The most extraordinary colours of the evening belong to Karen Cargill's servant Brangäne (pictured above with Melton), sounding instrumental in her Act Two nightwatch; she may be a mezzo, but she could be an Isolde in the making, though best that she first sings Berlioz's Dido, this Wagnerian heroine's true predecessor, as Robin Ticciati wants her to (and ideally at Glyndebourne, with Skelton as Aeneas, please). Matthew Rose shakes the foundations as "betrayed" King Mark.

Two other singers amaze. The most extraordinary colours of the evening belong to Karen Cargill's servant Brangäne (pictured above with Melton), sounding instrumental in her Act Two nightwatch; she may be a mezzo, but she could be an Isolde in the making, though best that she first sings Berlioz's Dido, this Wagnerian heroine's true predecessor, as Robin Ticciati wants her to (and ideally at Glyndebourne, with Skelton as Aeneas, please). Matthew Rose shakes the foundations as "betrayed" King Mark.

It's all the more remarkable that Cargill and Rose triumph given unfortunate get-up and some of the evening's worst concepts. Dramatically, you can see why Kramer wantedBrangäne and Kurwenal to be mincing courtiers - she with brillo-pad Marge Simpson hair, he as Jacobean fop, at odds with his butch music - but their constant campery and fussing over dressing up their mistress and master detract from some key narrative in Act One. Would a newcomer, for instance, pay proper attention to Tristan and Isolde's back story as delivered by the wrathful heroine? And why arraign the lovers for their meeting, only to undress them before the King's arrival?

In Act Two, a greybeard Mark - no reason why he should be this old, since he's only the teenage Tristan's uncle - comes on lovers not in flagrante delicto but in the throes of death. It's hard enough at the best of times to feel sympathy for a king who's contracted a marriage of convenience, but for this one to make it all about himself when the wife and friend he's supposed to revere may expire at any moment is an absurdity only Rose's incredibly sympathetic forcefulness can cast aside. (Pictured above, Rose with Cargill, Skelton and Melton)

In Act Two, a greybeard Mark - no reason why he should be this old, since he's only the teenage Tristan's uncle - comes on lovers not in flagrante delicto but in the throes of death. It's hard enough at the best of times to feel sympathy for a king who's contracted a marriage of convenience, but for this one to make it all about himself when the wife and friend he's supposed to revere may expire at any moment is an absurdity only Rose's incredibly sympathetic forcefulness can cast aside. (Pictured above, Rose with Cargill, Skelton and Melton)

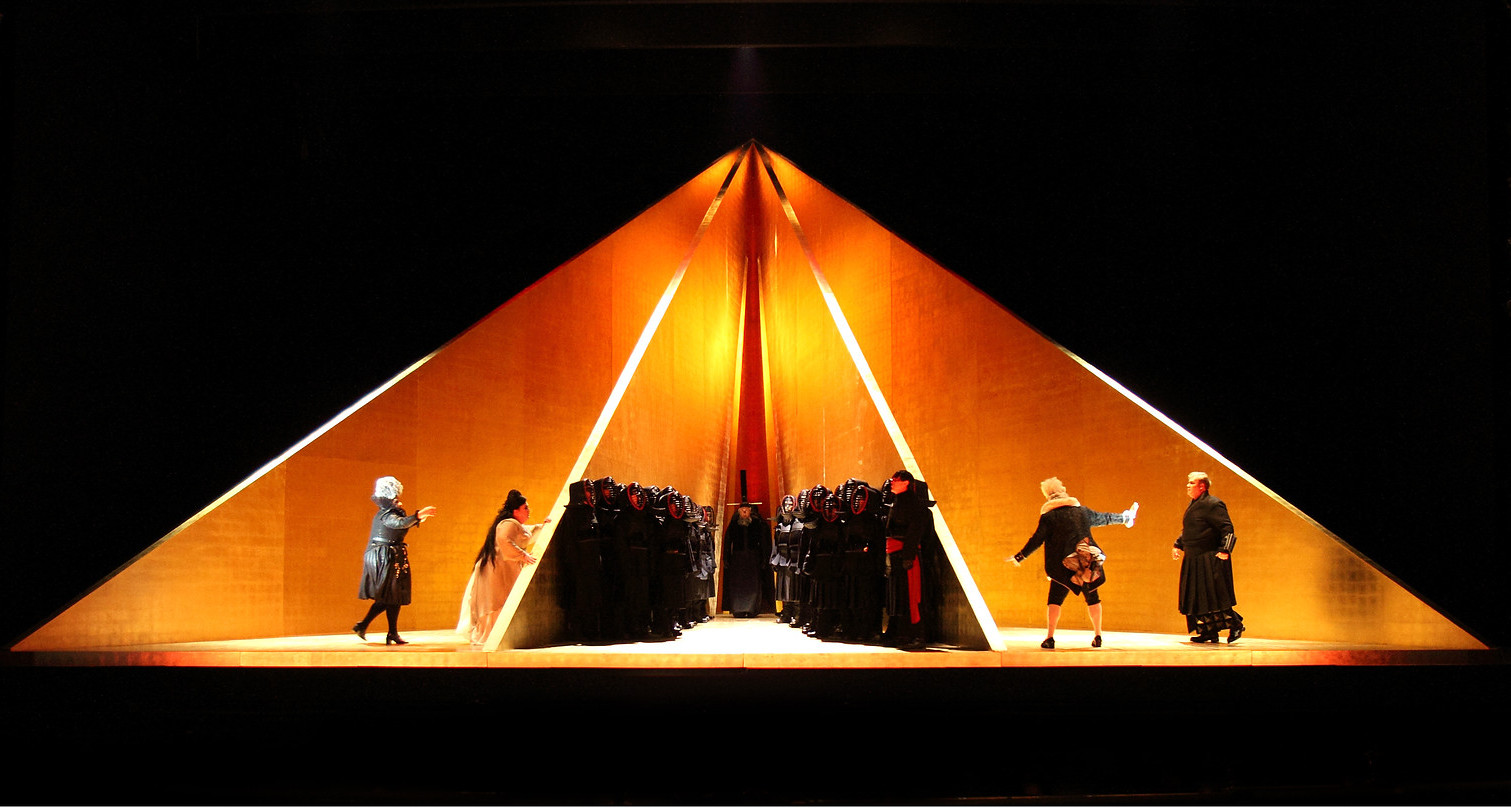

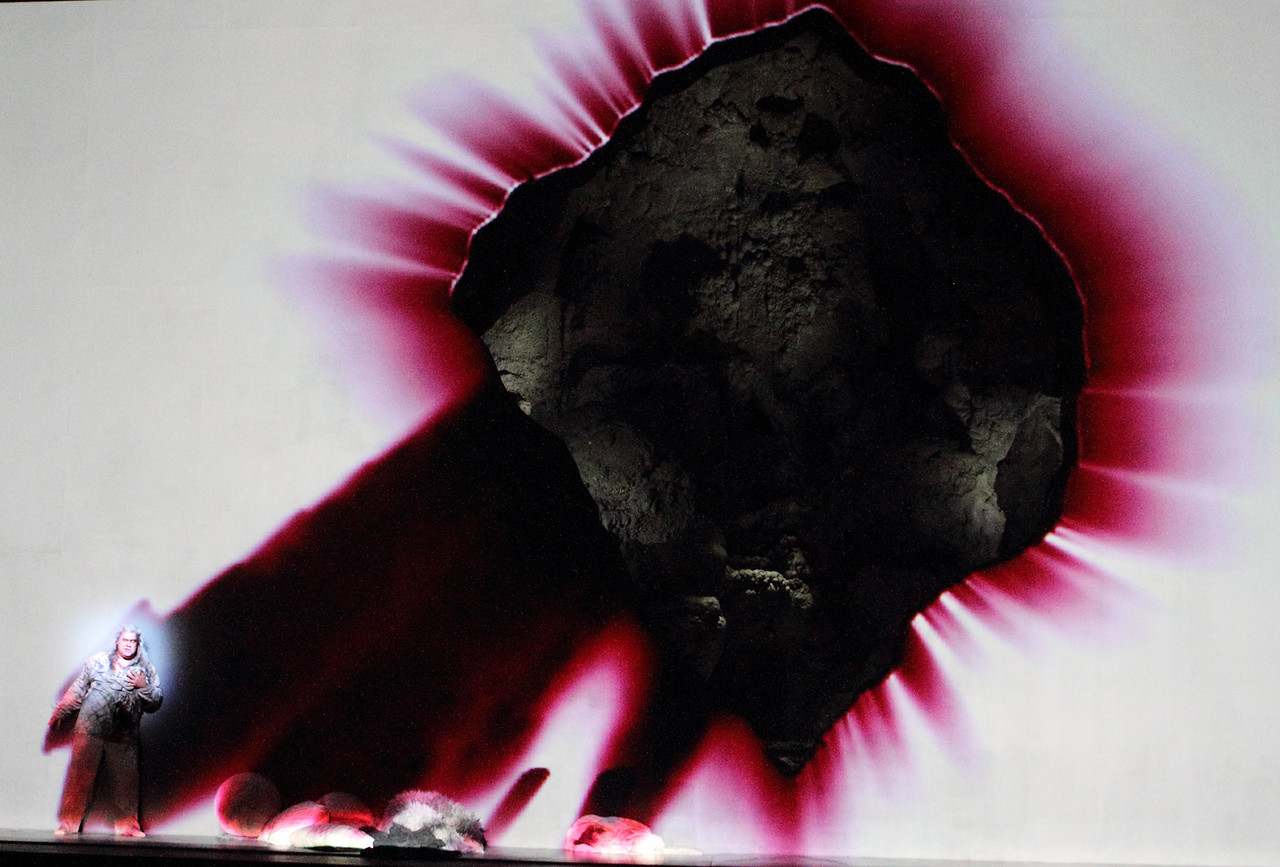

Even so, Kramer's idea of the preceding "Night of Love" as an extended episode of suicidal self-harming isn't a bad one; it's no more confused than Wagner's appropriation of Schopenhauer's supposed transcendence over life's wheel of will and desire to his own bizarre notion that the lovers can actually be united on whatever the other side might be. Kapoor's giant moon-as-half-eaten cheese certainly adds to the hypnotic slow-motion horror of the scene, and the claylike substance makes a strong reappearance connected to the flow of dark blood from Tristan's unquenchable wound in Act Three. If only the First Act had co-operated in the whole. The deconstructed wooden pyramid with its three "rooms" (pictured below) should at least allow the singers to be visible in all parts of the theatre since they're at the front of the stage, but reports from the side were that one voice was magnified at the expense of another.

If those spectators were getting more of Heidi Melton's Isolde than Skelton's Tristan, they should not have been too disconcerted. Melton has a warm and lovely middle range, and she's good with the text, though the acting is limited to much rolling of eyes. She can certainly just about manage Isolde now, but she won't be singing anything in five years' time if she persists with the role; this is a voice better suited to Wagner's Elsa and Elisabeth - which she sang beautifully in the Proms Tannhäuser three years ago. The top is effortful in two of the three passages of what Richard Strauss called "erotic screaming", and she only just makes the end of the Liebestod (or "Transfiguration through Love" as it truly becomes here - I won't spoil Kramer's last idea, one of his best).

Melton doesn't always get the help she needs from Edward Gardner in the pit. After his perfectly flowing Mastersingers last season, he seemed less certain of pace here, indulging too many slow tempi when the action needs to move forward. The Prelude's steady kindling was fine: towards the climax I could swear the Coliseum's gold-inflected 2004 dropcloth was levitating long before it actually did. But Isolde's narrative loses energy, and last night Melton was stretched too far by the crucial phrase in which she tells Brangäne how the wounded Tristan in Ireland looked into her eyes as she was about to kill him.

The string sound is rich, but the players don't quite burn for their former music director. There's another dip in tension before the crucial potion taking, too, though not before the heart of the Act Two love duet, thanks to a whopping cut (Kramer and Gardner need to trust Wagner and their audience). The point of repose doesn't quite flow or glow as it did under Pappano in the intelligent and consistent Christof Loy production at the Royal Opera, surely the best of recent years.

Act Three works best thanks mostly to Skelton's resilience in bloody extremes (pictured above), though I pity Craig Colclough, the vocally stalwart Kurwenal, having to jabber around as a scabby old Feste or Fool (point taken in what Kramer has clearly read as more Beckett nullity than Shakespearean raging). At the denouement Frieder Weiss's video projection - stunning when it works properly - goes berserk and the awkward follow-spots of Paul Anderson's erratic lighting give way to a flickering mess; thankfully the last tableau is static. Never dull, sometimes annoying, at best - if only fitfully - electrifying, the end result does let Wagner shine through. And three stars in his universe would be four and a half in any other.

Add comment