How often do you leave a production of Shakespeare's most layered drama in tears, thinking "what an astonishing play!" even more than "what a fine Hamlet!" (or not)? Last night the Bard proved even greater than his Dane. Not that Andrew Scott was ever less than mesmerising and unpredictable. But it was Robert Icke, a director you might expect to play fast and loose with text and structure, who in giving us more Hamlet than most these days respected the slow burn and the long vision, with a few surprises but no gimmicks on the journey.

Scott will not disappoint either his huge fan club or Hamlet hunters. His Prince's rages are terrifying, triggered by the conjuration of the ghost from close-circuit security screens – a very real father allowing the bereaved son to express physical affection; there's no ambiguity about his appearances, however much Hamlet might doubt their provenance. I fear slightly for Scott's vocal self-preservation in extremis; his range is higher than usual, embracing a spooky falsetto that must be unique among leading men, but also throat-ripping just below the break. There's a long way to go in the run, though selfishly I'm glad he pushed it so far last night.

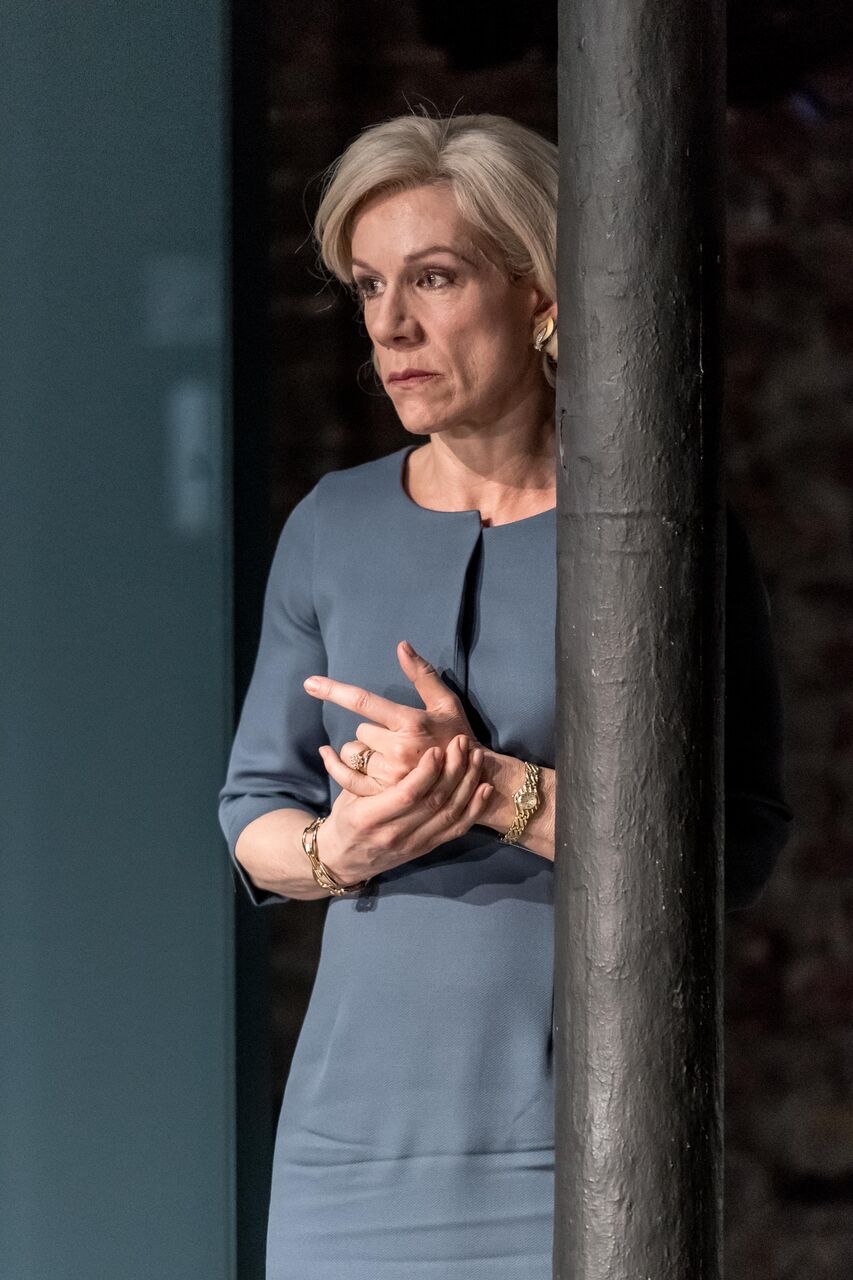

The real revelation, though, comes in the quiet talking, broaching an intimacy which the Almeida encourages (what a privilege to hear a top-notch Hamlet at such close range). We're in no doubt where this bewildered young man's heart lies: at first, with Ophelia; with the memory of his old relationship with a female Guildenstern (Amaka Okofor, sympathetic); when pushed, with his mother; but above all in directing the play-within-a-play, a gamble enhanced by David Rintoul doubling Ghost and Player King, taking up with supreme eloquence the Pyrrhus speech from the well-educated prince who knows it so well. Icke encourages absolute unhurried naturalness in the test of the play itself, shared between Rintoul and Marty Cruickshank as Player Queen (pictured below). Hamlet's got the video camera trained on Claudius, sitting in the front row until he gets up and simply walks across the stage rather than crying for lights. The assembled crowd sits in anxious silence, and so do we, until the cue for the first interval strikes.

That's brilliant toying with the audience. So, too, are Hamlet's soliloquies, delivered very directly and mostly quietly to us, Scott valuing the silences and pauses, using eloquent arm and hand gestures held high to articulate the sense. The best of all, though, is a monologue rather than a voice in the head: Hamlet's to Horatio with the skull of Yorick in his hand. The quiet philosophy is well established by Barry Aird's gravedigger. When you listen to this reflection on mortality in Scott's performance, you have to wonder if any poet ever captured thoughts on transience and the passing of the world's glory more eloquently.

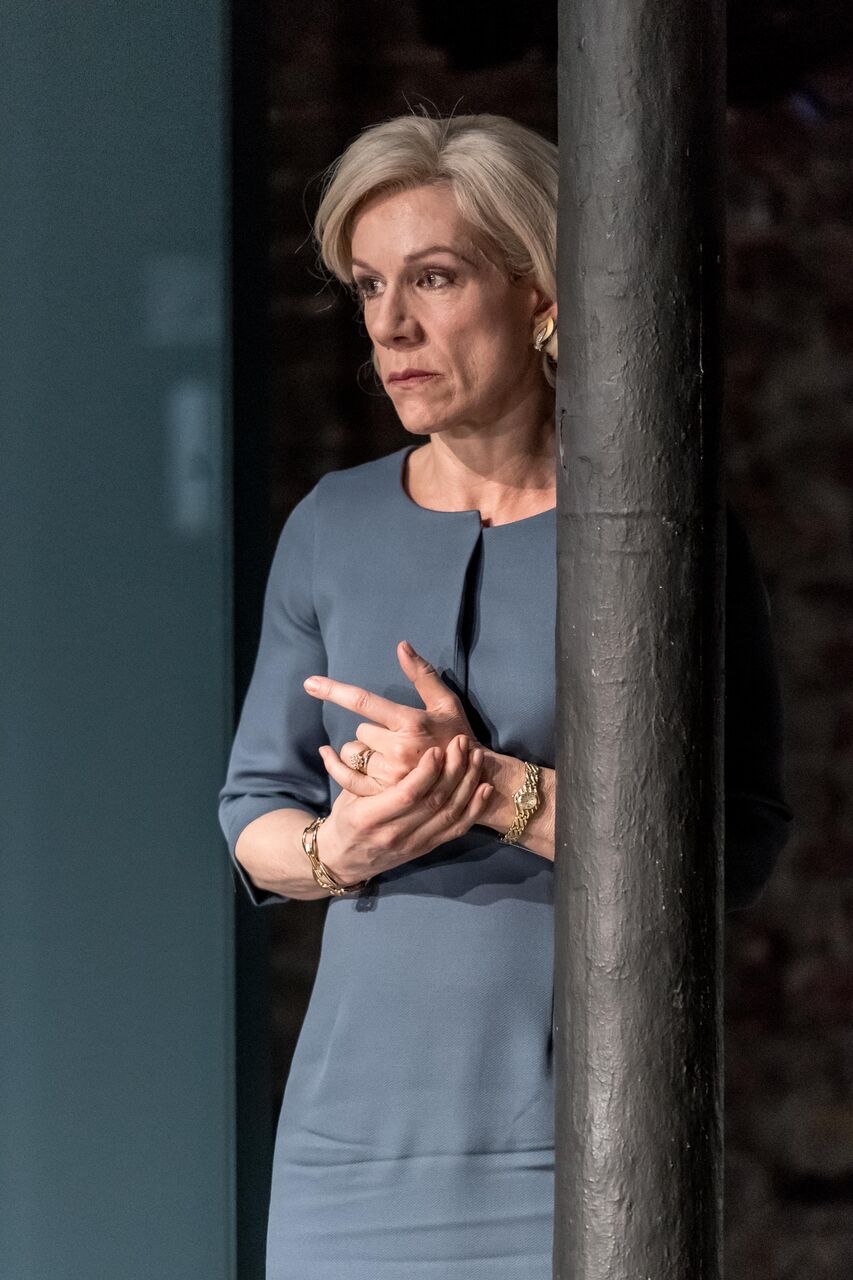

Icke is master of pace and tension, though not everyone in the ensemble really comes up to the mark. Luke Thompson's Laertes is a hollow counterfeit of Scott's Hamlet – maybe that's the point – and Angus Wright, as in Icke's Oresteia, seems too much of a stuffed shirt to play a calculating authority figure like Claudius (though that, too may be the intention). Reaction, though, is all – supremely so from Juliet Stevenson's Gertrude (pictured below) in as vivid a climactic mother-son scene as I've ever witnessed; the terrorised makes her mark as much as the terroriser, while the body-dragging and its aftermath are among Scott's most hallucinatory moments.

This Gertrude's stares and defiant flickers at the man she fell in lust with once she knows the truth are compelling, too; you can't take your eyes off Stevenson, and you're drawn in to what is, along with Rintoul's, the most beautiful verse-speaking of the evening, the "willow grows aslant a brook" narrative. Jessica Brown Findlay rises to the challenge of Ophelia's madness, taking over the mantle of Hamlet's calms and psychotic rages in his absence. Peter Wight gauges her father's control-freakery at just the right naturalistic level.

This Gertrude's stares and defiant flickers at the man she fell in lust with once she knows the truth are compelling, too; you can't take your eyes off Stevenson, and you're drawn in to what is, along with Rintoul's, the most beautiful verse-speaking of the evening, the "willow grows aslant a brook" narrative. Jessica Brown Findlay rises to the challenge of Ophelia's madness, taking over the mantle of Hamlet's calms and psychotic rages in his absence. Peter Wight gauges her father's control-freakery at just the right naturalistic level.

Quietly remarkable, Hildegard Bechtler's sets work in tandem with Natasha Chivers' lighting and the best of Tom Gibbons' sound – I'm not so keen on its ambient omnipresence, but the use of Dylan songs is superb – to change scenes with cinematic ease. It's good to have the Norwegian threat played out on Danish television, and the fencing filmed, too, with some of the crucial lines purposefully drowned out by Dylan.

I won't spoil the visual wonder of what happens as Hamlet approaches the shores of the undiscovered country before TV gives him a state funeral (and a final publicity shot of happy royals which is more than just deadly ironic). Suffice it to say that the image which has most stuck with me from any Hamlet is when Ingmar Bergman had the besmirched Ophelia, restored to her flower-crowned innocence, emerge from the huddle of umbrella-holding mourners at her funeral and walk slowly downstage centre and off. Icke and his team achieve a parallel wonder here. The overall impact is to be taken in tandem with his Mary Stuart, a play of almost equal resonance with no less revelatory performances, as a diptych to match the wonders of his Greek season (the all-day Iliad and Odyssey readings; for me, the Oresteia not so much). What on earth on the same level can he turn his attention to next?

OTHER GREAT DANES

Andrius Mamontovas, Globe to Globe. Lithuanian take on the Danish play puts on a frantic disposition

Benedict Cumberbatch, Barbican. Visuals threaten to swamp Shakespeare – and, yes, Sherlock

David Tennant, RSC/BBC. Star looks for life in an infinite space beyond the Tardis

David Tennant, RSC/BBC. Star looks for life in an infinite space beyond the Tardis

Lars Eidinger, Schaubühne Berlin. Acrobatic Hamlet, outshone by the earth and the rain

Maxine Peake, Royal Exchange, Manchester. An underwhelming production, but Peake is gripping as the young Prince

Michael Sheen, Young Vic. Sheen is riveting as the crazed Danish Prince in Ian Rickson's terrifying psychiatric-hospital staging

Rory Kinnear, National Theatre. Kinnear isn’t a romantic Prince, but an unsettled, battling one in Nicholas Hytner's staging which is modern, militaristic and unfussy

Overlear: Robert Icke's career so far

This Gertrude's stares and defiant flickers at the man she fell in lust with once she knows the truth are compelling, too; you can't take your eyes off Stevenson, and you're drawn in to what is, along with Rintoul's, the most beautiful verse-speaking of the evening, the "willow grows aslant a brook" narrative.

This Gertrude's stares and defiant flickers at the man she fell in lust with once she knows the truth are compelling, too; you can't take your eyes off Stevenson, and you're drawn in to what is, along with Rintoul's, the most beautiful verse-speaking of the evening, the "willow grows aslant a brook" narrative.  David Tennant

David Tennant