As the UK prepares for a particularly severe cold snap, the opening of David Hockney’s major retrospective at Tate Britain brings a welcome burst of Los Angeles light and colour and Yorkshire wit and warmth. The exhibition, which opens in the lead-up to Hockney’s 80th birthday, will be deservedly popular – for many people, Hockney’s work is simply bright and beautiful. But the show also seeks to reveal the serious and consistent nature of Hockney’s interrogation of the meaning of picture-making, and his preoccupation with the joyous and rather subversive business of “looking”.

The curators have brought together Hockney’s youthful paintings from the 1960s (the earliest work is, in fact, an earnest self-portrait drawing of 1954 of the 17-year-old artist), with the iconic and intimate works of the intervening decades, right up to his brash (and less successful) recent paintings of 2016 – with the inclusion of two new pictures of the blue and red terrace of the artist’s present-day Hollywood home (overlooking lush gardens reminiscent of a Rousseau jungle) made especially for the exhibition. (Pictured below: Garden, 2015 © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt) As we make the journey through Hockney’s oeuvre – one that the artist has also clearly enjoyed revisiting – we move from his formative pictures as a student at the Royal College of Art in London, through to the breakthrough Los Angeles paintings – typified by A Bigger Splash (Hockney first moved to the Hollywood Hills in 1979) – to the first big room of the show: a stunning display that reunites Hockney’s celebrated series of large double portraits.

As we make the journey through Hockney’s oeuvre – one that the artist has also clearly enjoyed revisiting – we move from his formative pictures as a student at the Royal College of Art in London, through to the breakthrough Los Angeles paintings – typified by A Bigger Splash (Hockney first moved to the Hollywood Hills in 1979) – to the first big room of the show: a stunning display that reunites Hockney’s celebrated series of large double portraits.

Despite the variety of media and subject matter, consistent themes emerge. Thus we find Hockney continually playing with the notion of flat, two-dimensional picture-making (revealing the inherent artifice, while trying to make the experience more "true"); critiquing the art fashions of the time (particularly abstract and conceptual art); showily improvising in the style of the artists who capture his interest (such as Dubuffet, Picasso and Munch); raunchily exploring homo-erotic relationships and his own sexuality (at a time when homosexuality was still illegal in the UK); and urging us to question, engage with and examine what we see. Sometimes his artistic response is annoyingly puerile, while at others Hockney can be genuinely profound in the way he expresses personal encounters with people and places.

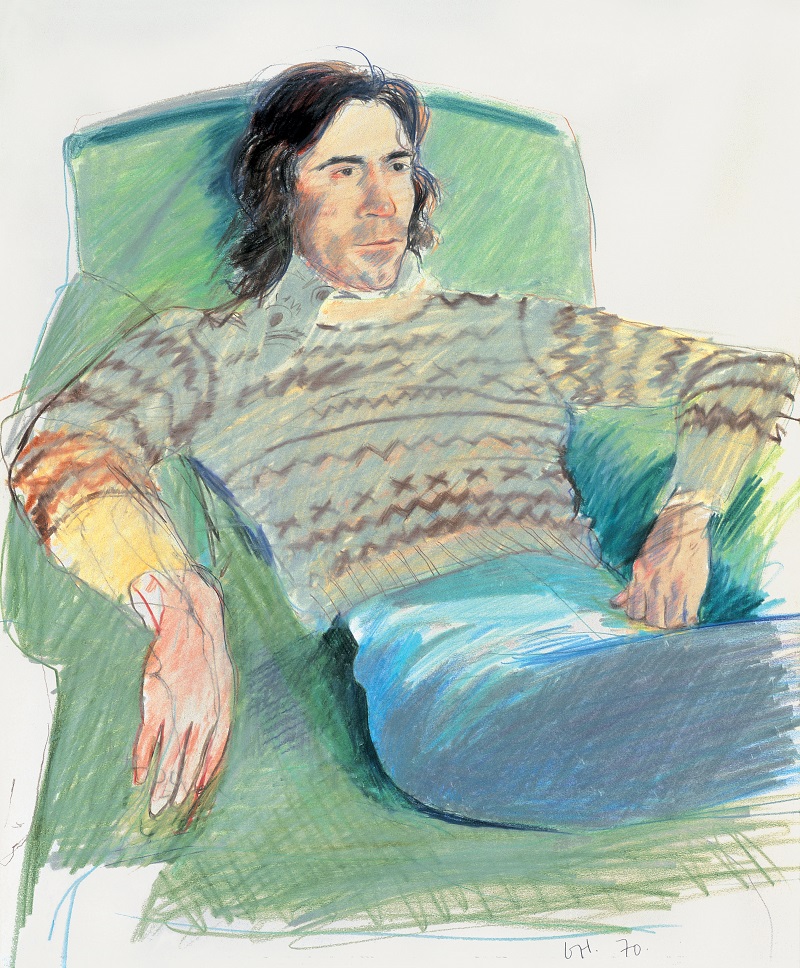

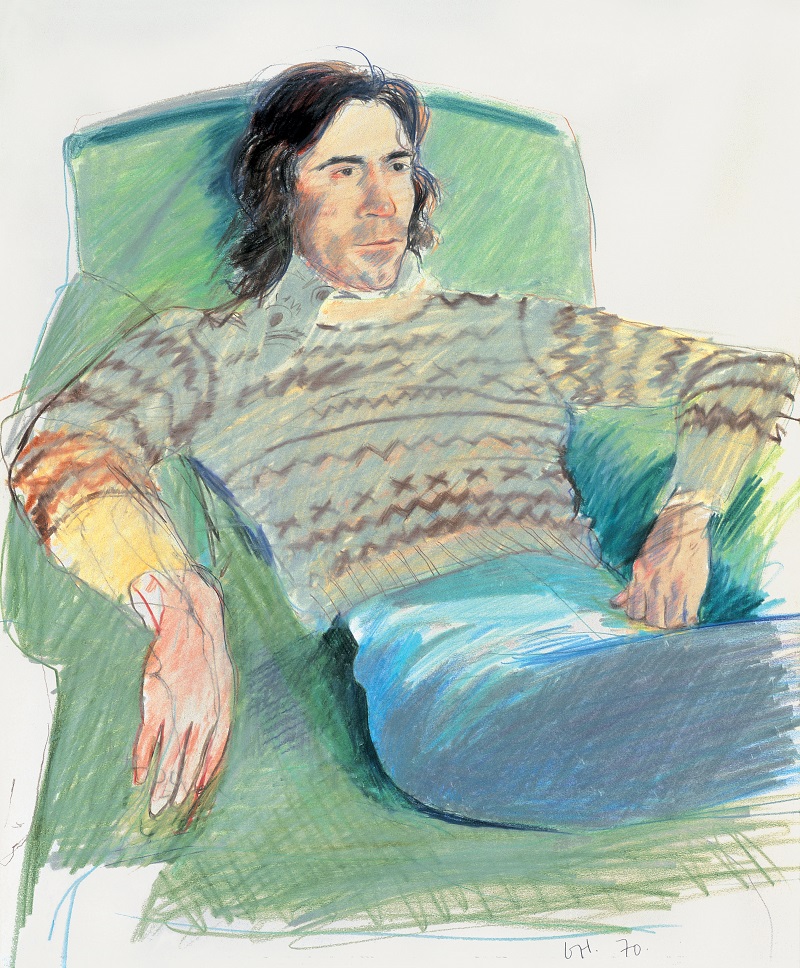

Hockney sees himself as a humanist: his reaction to the dominance of abstract art was to paint "pictures with people in": and not just any people. His sitters are usually friends, family or lovers. He came out early – while at college – deciding to embrace his homosexuality in his art; these paintings reflect his life and boyish humour, from escapades with early boyfriends to graffiti in the gent’s toilets. By being so constantly self-referential, Hockney became drawn to ambiguity, both in terms of the way we see the world, and the way the world sees us. (Pictured above right: Ossie Wearing a Fairisle Sweater, 1970. Private collection, London © David Hockney)

Hockney sees himself as a humanist: his reaction to the dominance of abstract art was to paint "pictures with people in": and not just any people. His sitters are usually friends, family or lovers. He came out early – while at college – deciding to embrace his homosexuality in his art; these paintings reflect his life and boyish humour, from escapades with early boyfriends to graffiti in the gent’s toilets. By being so constantly self-referential, Hockney became drawn to ambiguity, both in terms of the way we see the world, and the way the world sees us. (Pictured above right: Ossie Wearing a Fairisle Sweater, 1970. Private collection, London © David Hockney)

The relationship between the artist and the viewer is also central to this preoccupation. As a result, his work sets out to challenge the one-point perspective enshrined by single-lens cameras and crystallised in the rigid perspective constructions of Renaissance painting. Most of Hockney’s work sets out to undermine this "paralysed Cyclops’s" view of the world, as he calls it – though it is perhaps as much a way of thinking as a way of seeing. For Hockney, however, the question seems to be why would anyone choose to present a world that is so full of variation and contradictions in such a prescriptive way, and not actively invite the viewer’s eyes to wander, to embrace peripheral and contradictory viewpoints, or to mischievously seize on a particular detail?

The expansive sun-flattened spaces of Los Angeles, with their geometric buildings, blue skies and swimming pools, may seem to have the stillness that one associates with a Renaissance landscape or abstract canvas – but the geometry is often disturbed by the human presence. One of the surprises of the exhibition is Hockney’s corresponding love of areas of surface detail (like the meticulously painted splash). In the double portraits – such as the 1968 portrait of Christopher Isherwood and his partner Don Bachardy – the great open spaces of LA are exchanged for a defined domestic space, delineated by the device of a shuttered window and the static charge between the two sitters.

Hockney’s interest in the human is intimately entwined with a feeling for the character of a place. The exhibition includes the winding hilly landscapes of his home in the Hollywood Hills (their fauvist colours capturing the dizzying journey to his Santa Monica studio) and the glowing landscapes of the Grand Canyon, followed by a contrasting room of Hockney’s expansive Yorkshire landscapes – selected from the many canvases that Hockney produced for his 2012 blockbuster at the Royal Academy. In these gentler Yorkshire landscapes – which are a celebration of the English seasons, especially the spring when the hedgerows burst with hawthorn blossoms – Hockney continues to play with the language of painting, using exaggerated perspectives and heightened colour, set off by areas of flat decoration depicting cow parsley and grass verges. (Pictured above left: Going Up Garrowby Hill, 2000. Private collection, Topanga, California © David Hockney)

Hockney’s interest in the human is intimately entwined with a feeling for the character of a place. The exhibition includes the winding hilly landscapes of his home in the Hollywood Hills (their fauvist colours capturing the dizzying journey to his Santa Monica studio) and the glowing landscapes of the Grand Canyon, followed by a contrasting room of Hockney’s expansive Yorkshire landscapes – selected from the many canvases that Hockney produced for his 2012 blockbuster at the Royal Academy. In these gentler Yorkshire landscapes – which are a celebration of the English seasons, especially the spring when the hedgerows burst with hawthorn blossoms – Hockney continues to play with the language of painting, using exaggerated perspectives and heightened colour, set off by areas of flat decoration depicting cow parsley and grass verges. (Pictured above left: Going Up Garrowby Hill, 2000. Private collection, Topanga, California © David Hockney)

This epic journey through the seasons continues in a room of four nine-screen video installations – capturing multiple viewpoints as we travel with the artist through space. The final rooms are part analogue, part digital – moving from a fine series of 25 charcoal drawings chronicling the arrival of the Yorkshire Spring (contrasted rather pointlessly with the terrace-scenes made on Hockney’s return to LA), to the same preoccupations played out through Hockney’s exploration of the digital: numerous images made on the iPhone and iPad. The inclusion of a number of animated iPad drawings, which show step-by-step how the artist makes his marks, layers his colour, fixes the objects in his eye, allows the viewer to share in the show business of Hockney’s recent transformations of the perceived world. There is, fortunately, better business than "show business" to be had in this show.

Overleaf: browse a gallery of Hockney paintings from the exhibition

As we make the journey through Hockney’s oeuvre – one that the artist has also clearly enjoyed revisiting – we move from his formative pictures as a student at the Royal College of Art in London, through to the breakthrough

As we make the journey through Hockney’s oeuvre – one that the artist has also clearly enjoyed revisiting – we move from his formative pictures as a student at the Royal College of Art in London, through to the breakthrough  Hockney sees himself as a humanist: his reaction to the dominance of abstract art was to paint "pictures with people in": and not just any people. His sitters are usually friends, family or lovers. He came out early – while at college – deciding to embrace his homosexuality in his art; these paintings reflect his life and boyish humour, from escapades with early boyfriends to graffiti in the gent’s toilets. By being so constantly self-referential, Hockney became drawn to ambiguity, both in terms of the way we see the world, and the way the world sees us. (Pictured above right: Ossie Wearing a Fairisle Sweater, 1970. Private collection, London © David Hockney)

Hockney sees himself as a humanist: his reaction to the dominance of abstract art was to paint "pictures with people in": and not just any people. His sitters are usually friends, family or lovers. He came out early – while at college – deciding to embrace his homosexuality in his art; these paintings reflect his life and boyish humour, from escapades with early boyfriends to graffiti in the gent’s toilets. By being so constantly self-referential, Hockney became drawn to ambiguity, both in terms of the way we see the world, and the way the world sees us. (Pictured above right: Ossie Wearing a Fairisle Sweater, 1970. Private collection, London © David Hockney) Hockney’s interest in the human is intimately entwined with a feeling for the character of a place. The exhibition includes the winding hilly landscapes of his home in the Hollywood Hills (their fauvist colours capturing the dizzying journey to his Santa Monica studio) and the glowing landscapes of the Grand Canyon, followed by a contrasting room of Hockney’s expansive Yorkshire landscapes – selected from the many canvases that Hockney produced for his 2012 blockbuster at the

Hockney’s interest in the human is intimately entwined with a feeling for the character of a place. The exhibition includes the winding hilly landscapes of his home in the Hollywood Hills (their fauvist colours capturing the dizzying journey to his Santa Monica studio) and the glowing landscapes of the Grand Canyon, followed by a contrasting room of Hockney’s expansive Yorkshire landscapes – selected from the many canvases that Hockney produced for his 2012 blockbuster at the