Patrick Caulfield (1936-2005) is the greatest late 20th-century British painter the international art world has never heard of. This quietly magnificent exhibition of about 35 paintings, most of them very large, may at last bring about a satisfactory reversal of fortune. Although some of the paintings are 50 years old, they could have been painted tomorrow. Their style, wit, irony and melancholy, tempered by contradictory moods of quiet cynicism and sensual pleasure in the observed world, seem utterly contemporary.

The images are theme and variations: flatly painted blocks of bold colour – oranges, reds, purples, lilacs – outlined in black, depict still life, interiors of cafés, bars, restaurants, offices, apartments, patios, courtyards. They suggest the absent presence, as almost all are empty of people, with a handful of exceptions. Happy Hour, 1996, is a brilliant range of reds, punctuated by blues and lilac, that somehow convincingly show us the interior of a bar; but centrally placed there is an exquisitely realistic reflection in a wine glass of a waiter – or a drinker, delicately suggestive. There are windows that look out at nothing, and brilliantly lit lamps that shed no light on anything. The emptiness, the loneliness, can be intense, almost uncomfortably so. These are not paintings for the faint-hearted; this is a heartbreaking show.

The interiors and domestic exteriors, suggestive both of private houses and boutique hotels, are enlivened with allusions to a shared and sophisticated literary and visual culture, from the cubist painters to Ernest Hemingway. The author is represented handily by a bull’s head on a green wall, overlooking an elegant still life vignette of a white cup on a pewter plate, reminiscent of Zurbaran, in Hemingway Never Ate Here, 1999. Braque Curtain, 2005, one of his last paintings, takes a pattern from a textile depicted in Braque’s The Duet, and riffs on it.

The interiors and domestic exteriors, suggestive both of private houses and boutique hotels, are enlivened with allusions to a shared and sophisticated literary and visual culture, from the cubist painters to Ernest Hemingway. The author is represented handily by a bull’s head on a green wall, overlooking an elegant still life vignette of a white cup on a pewter plate, reminiscent of Zurbaran, in Hemingway Never Ate Here, 1999. Braque Curtain, 2005, one of his last paintings, takes a pattern from a textile depicted in Braque’s The Duet, and riffs on it.

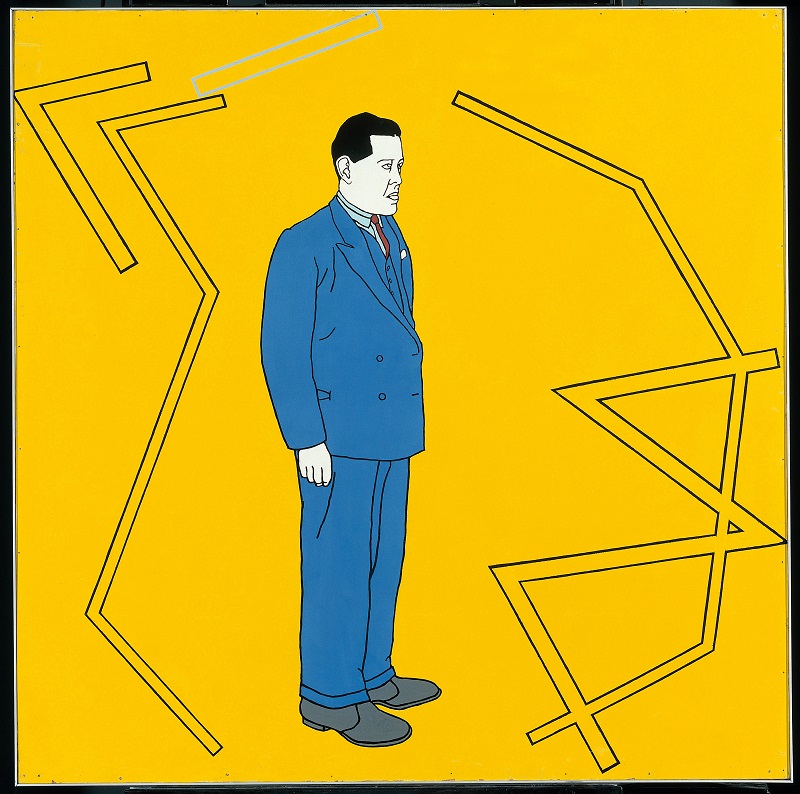

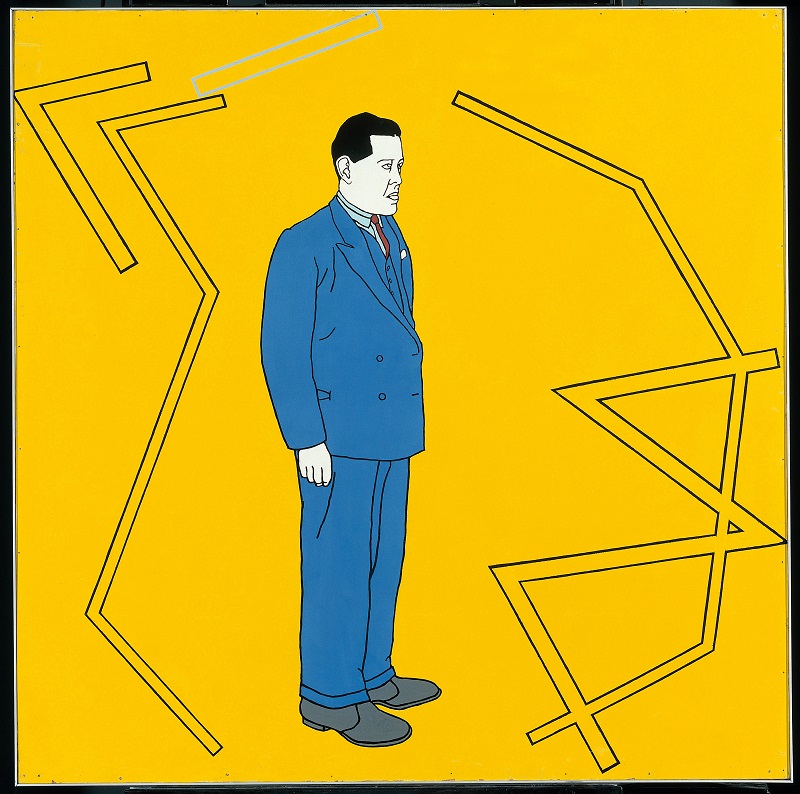

The earlier paintings show an artist finding his voice: Pottery, 1969 (pictured right, Tate © The estate of Patrick Caulfield), perhaps echoes William Nicholson’s huge still lifes of endless ceramic vessels. Two purple containers in the vibrant array of endlessly replicated and overlapping forms are the only time Caulfield uses modulated, dappled hues as opposed to his characteristic deployment of uninflected blocks of colour. And there is a stylised, pared-down, blue-suited Portrait of Juan Gris, 1963 (pictured below, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester © The Estate of Patrick Caulfield), depicting a hero of Caulfield’s framed by two choreographed twisted geometric lines, subtly suggestive of the infinitely more complex and inventive dances of cubism. Art is a business too, the portrait indicates, solemn and serious as well as lively, unexpected and full of twists and turns.

And there is many a twist and turn to come. From the 1970s on, Caulfield, often using postcards and photographs as sources, inserts with superb technique visual aperçus: realistically painted landscape, as in the Castle of Chinon in After Lunch, 1975, as though a view from the restaurant window; roses galore luxuriantly blooming in a variety of paintings; wallpaper patterns including William Morris, in Green Drink, 1984, which even includes a piece of rolled-up newspaper, partly outlined, partly realistic (another shade of cubism). And there is a riot of realistic food, from paella to mussels in Still Life: Maroochydore, 1980-1, with a semi-realistic river and village view through a window, and a china plate hung on the faux wood of the restaurant wall.

And there is many a twist and turn to come. From the 1970s on, Caulfield, often using postcards and photographs as sources, inserts with superb technique visual aperçus: realistically painted landscape, as in the Castle of Chinon in After Lunch, 1975, as though a view from the restaurant window; roses galore luxuriantly blooming in a variety of paintings; wallpaper patterns including William Morris, in Green Drink, 1984, which even includes a piece of rolled-up newspaper, partly outlined, partly realistic (another shade of cubism). And there is a riot of realistic food, from paella to mussels in Still Life: Maroochydore, 1980-1, with a semi-realistic river and village view through a window, and a china plate hung on the faux wood of the restaurant wall.

So he teases and amuses, sometimes even quietly showing off, with his ability to play with the conventions of abstraction, figuration, realism, and with the variations possible with methods of drawing and painting. The whole is an exhibition about how you convince the spectator, and possibly even the artist himself, that we are seeing something real, when in fact (as brilliantly summed up in Maurice Denis’s evocative remark of 1890) we should remember that a picture – before being a war horse, a nude woman, or telling some other story – is essentially a flat surface covered with colours arranged in a particular pattern.

Gary Hume, born in 1962, is the Young British Artist who came to fame partly by painting in zinging colour the mundanity of hospital doors, and one such door, entitled How to Paint a Door, provides the entrance into the Tate exhibition. It cleverly opens into the gallery to show us a two-panel painting, Innocence and Stupidity. Then we are treated to a series of huge paintings, almost invariably gloss paint on aluminium, sometimes almost incandescent or luminous in the dazzle of sweeps of colour. One sculptural enamel paint on bronze is called Back of a Snowman, though there is neither back nor front, as there is no face.

Gary Hume, born in 1962, is the Young British Artist who came to fame partly by painting in zinging colour the mundanity of hospital doors, and one such door, entitled How to Paint a Door, provides the entrance into the Tate exhibition. It cleverly opens into the gallery to show us a two-panel painting, Innocence and Stupidity. Then we are treated to a series of huge paintings, almost invariably gloss paint on aluminium, sometimes almost incandescent or luminous in the dazzle of sweeps of colour. One sculptural enamel paint on bronze is called Back of a Snowman, though there is neither back nor front, as there is no face.

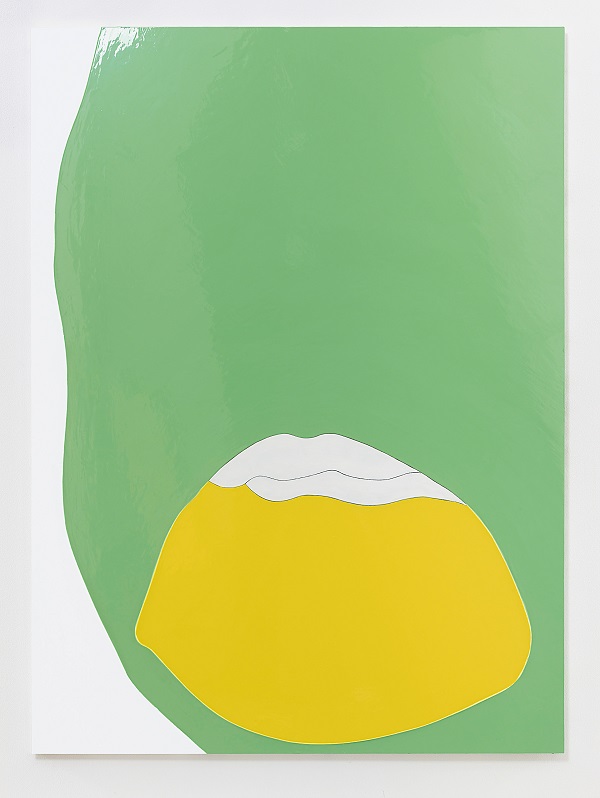

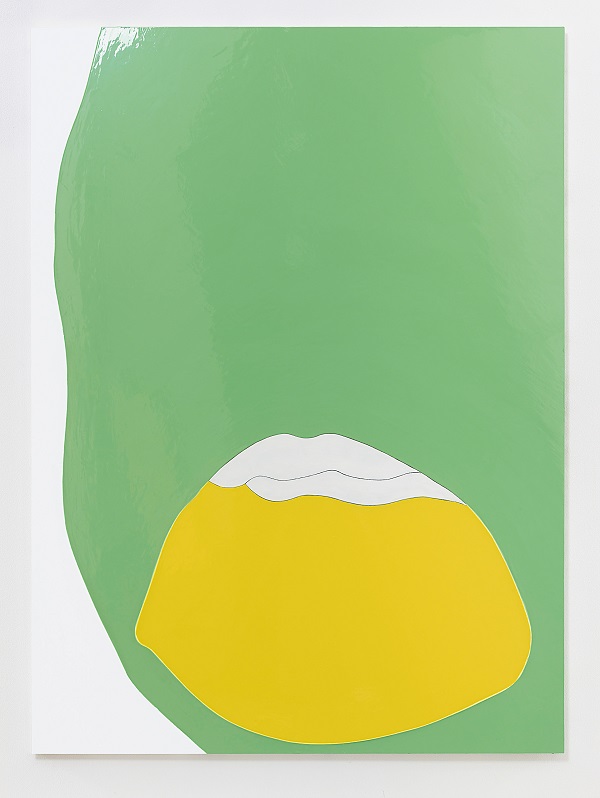

There is energy aplenty, and with gigantic human forms shown just as undifferentiated lumps with titles like Two Minds. There are enormous abstracted flowers, and floral-human forms: Nicola as a Flower is both dancing and drooping. The titles do help, but the green, white and yellow extravaganza, Anxiety and the Horse: Angela Merkel, 2011 (pictured above, Matthew Marks Gallery © Gary Hume), does seem a step too far. The colour and shine throughout are stupendous; this is really high-class décor.

The sheer energy of painting in the late 20th and early 21st centuries is demonstrated in the Tate’s pairing of two English painters, generations apart, but both of them visual wits and inspired colourists. However, there is a fascinating difference: where Caulfield is subtle and endlessly interesting, Hume is brutal, direct, and hits the viewer on the head. Hume is what I call one-lineism art. You feel that once you’ve seen it, you get it. With Caulfield, every time you see a painting you see something you have not noticed before. This is painting that keeps on giving, the imagery dazzlingly memorable, and its emotional content captivating, long-lasting and affecting. His beautiful paintings are meditations on not only where we are, but on what we feel.

GREAT POP ART RETROSPECTIVES

Allen Jones, Royal Academy. A brilliant painter derailed by an unfortunate obsession

Andy Warhol: The Portfolios, Dulwich Picture Gallery. An exhibition of still lifes which are anything but still

Ed Ruscha: Fifty Years of Painting, Hayward Gallery. First British retrospective for a modern master

Ed Ruscha: Fifty Years of Painting, Hayward Gallery. First British retrospective for a modern master

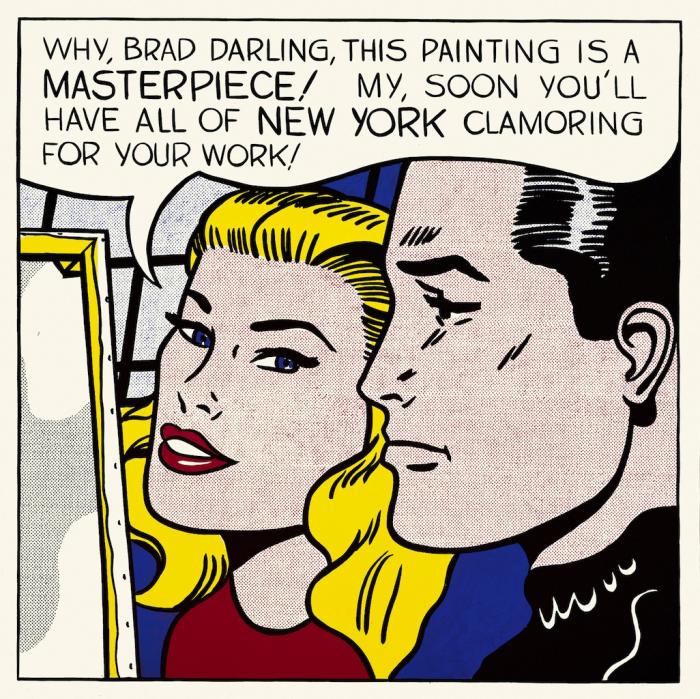

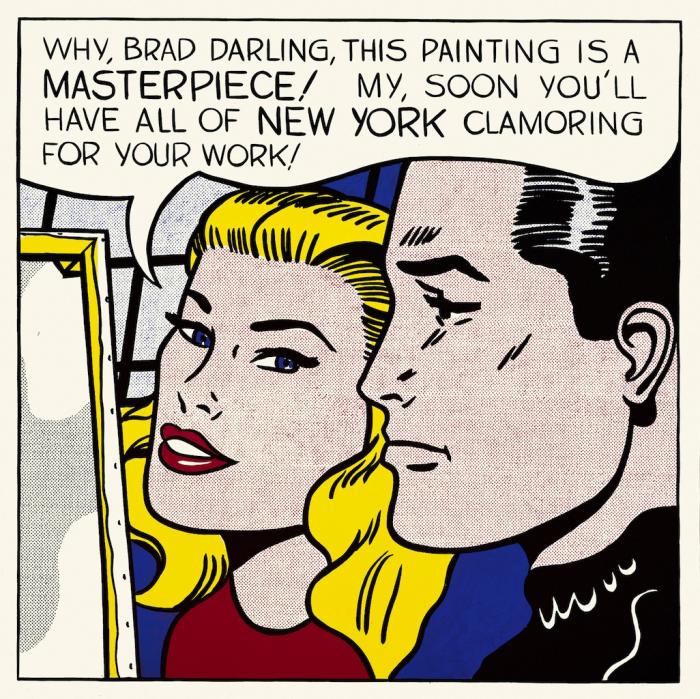

Lichtenstein: A Retrospective, Tate Modern. The heartbeat of Pop Art is given the art-historical credit as he deserves (pictured above, Lichtenstein's Masterpiece, 1962)

Pauline Boty: Pop Artist and Woman, Pallant House Gallery. The paintings are wonderful, but the curator does a huge disservice to this forgotten artist

Richard Hamilton, Tate Modern /ICA. At last, the British 'father of Pop art' gets the retrospective he deserves

Overleaf: browse a gallery from the exhibition

The interiors and domestic exteriors, suggestive both of private houses and boutique hotels, are enlivened with allusions to a shared and sophisticated literary and visual culture, from the cubist painters to Ernest Hemingway. The author is represented handily by a bull’s head on a green wall, overlooking an elegant still life vignette of a white cup on a pewter plate, reminiscent of Zurbaran, in Hemingway Never Ate Here, 1999. Braque Curtain, 2005, one of his last paintings, takes a pattern from a textile depicted in Braque’s The Duet, and riffs on it.

The interiors and domestic exteriors, suggestive both of private houses and boutique hotels, are enlivened with allusions to a shared and sophisticated literary and visual culture, from the cubist painters to Ernest Hemingway. The author is represented handily by a bull’s head on a green wall, overlooking an elegant still life vignette of a white cup on a pewter plate, reminiscent of Zurbaran, in Hemingway Never Ate Here, 1999. Braque Curtain, 2005, one of his last paintings, takes a pattern from a textile depicted in Braque’s The Duet, and riffs on it. And there is many a twist and turn to come. From the 1970s on, Caulfield, often using postcards and photographs as sources, inserts with superb technique visual aperçus: realistically painted landscape, as in the Castle of Chinon in After Lunch, 1975, as though a view from the restaurant window; roses galore luxuriantly blooming in a variety of paintings; wallpaper patterns including William Morris, in Green Drink, 1984, which even includes a piece of rolled-up newspaper, partly outlined, partly realistic (another shade of cubism). And there is a riot of realistic food, from paella to mussels in Still Life: Maroochydore, 1980-1, with a semi-realistic river and village view through a window, and a china plate hung on the faux wood of the restaurant wall.

And there is many a twist and turn to come. From the 1970s on, Caulfield, often using postcards and photographs as sources, inserts with superb technique visual aperçus: realistically painted landscape, as in the Castle of Chinon in After Lunch, 1975, as though a view from the restaurant window; roses galore luxuriantly blooming in a variety of paintings; wallpaper patterns including William Morris, in Green Drink, 1984, which even includes a piece of rolled-up newspaper, partly outlined, partly realistic (another shade of cubism). And there is a riot of realistic food, from paella to mussels in Still Life: Maroochydore, 1980-1, with a semi-realistic river and village view through a window, and a china plate hung on the faux wood of the restaurant wall. Gary Hume, born in 1962, is the Young British Artist who came to fame partly by painting in zinging colour the mundanity of hospital doors, and one such door, entitled How to Paint a Door, provides the entrance into the Tate exhibition. It cleverly opens into the gallery to show us a two-panel painting, Innocence and Stupidity. Then we are treated to a series of huge paintings, almost invariably gloss paint on aluminium, sometimes almost incandescent or luminous in the dazzle of sweeps of colour. One sculptural enamel paint on bronze is called Back of a Snowman, though there is neither back nor front, as there is no face.

Gary Hume, born in 1962, is the Young British Artist who came to fame partly by painting in zinging colour the mundanity of hospital doors, and one such door, entitled How to Paint a Door, provides the entrance into the Tate exhibition. It cleverly opens into the gallery to show us a two-panel painting, Innocence and Stupidity. Then we are treated to a series of huge paintings, almost invariably gloss paint on aluminium, sometimes almost incandescent or luminous in the dazzle of sweeps of colour. One sculptural enamel paint on bronze is called Back of a Snowman, though there is neither back nor front, as there is no face. Ed Ruscha: Fifty Years of Painting

Ed Ruscha: Fifty Years of Painting