Blu-ray: A Gentle Creature

Descent into hell: Sergei Loznitsa’s vivisection of Russia, past and present

“To our enormous suffering!” There are many macabre vodka toasts, accompanied by some appropriately gruelling visuals, in A Gentle Creature, but that one surely best captures the beyond-nihilist mood of Sergei Loznitsa’s 2017 Cannes competition contender. It’s a film guaranteed to leave viewers – those who make it through to the end of its (somewhat overlong) 140-minute-plus run, that is – scrabbling to find words to describe what they have just seen. The likes of “visceral” or “phantasmagoric” somehow aren’t enough to catch the film’s mixture of horror and hallucination, both elements made all the more alarming for being embedded in a brutally concrete vision of Soviet-Russian reality.

Loznitsa knows the ex-Soviet world very well indeed and conveys its worst-dream qualities with pitiless stylistic precision. Born in Belarus, he trained as a scientist in Ukraine, then studied film in Moscow at the end of the 1990s, but has lived in Western Europe for close on two decades now. Whatever issues he has with the character of the country and/or its political regime(s), Russian nevertheless remains the working language (though he’s a master of silence, too) of his impressive oeuvre which now encompasses some 18 documentaries, as well as feature films like his debut My Joy (2010) and its follow-up, the WWII partisan drama In the Fog (2012); his latest, Donbass, about the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine, played at Cannes this year.

It allows Loznitsa to build to a penultimate scene of unmatched, sickening cruelty

Appropriately he’s taken the title of A Gentle Creature – Une femme douce, in its French version: the film was made with a wide range of European backing – from Dostoevsky, though his script is actually only very loosely linked to that writer’s story of the same name (which was much more closely adapted by Robert Bresson in 1963). But Loznitsa is not chasing literal resemblance here, instead he’s wrung out the darkest drops from Dostoevsky’s 19th century nightmares (with a draught of Gogol, too), then strengthened them with a rich stylistic dose of Stalinist totalitarianism, and added an aftertaste of agonised post-Soviet anti-humanism that reeks of the blasted landscape of Putin’s present day. “In Russia, you are a stakeholder in hell,” he says succinctly in the booklet interview that accompanies this Blu-ray release.

Story is hardly the central element in an action that’s effectively a fabular chronicle of the misadventures of the film’s eponymous (and anonymous) heroine (Vasilina Makovetseva). Her sharply distinctive features betray little in reaction to the accumulating travails she encounters on a journey of tribulation, and that quality is more than matched by her forceful lack of words. It begins when her solitary provincial existence is disrupted when the parcel that she had sent to her husband in prison is returned without explanation, and she travels there to discover what has happened.

You could almost say that the film’s main presence is the prison itself, or rather the small surrounding town that lives off it parasitically (location filming, unsuited for Russia for obvious reasons, took place in Latvia, centred around just such an environment). It’s not just the sternly impenetrable building itself, or the reception windows (main picture) that offer visitors terse contact, but the whole human atmosphere, one in which “man is wolf”. From the ranks of exploiters and hanger-on prostitutes (pictured below), through the deceit of pretend-fixers and the cruelty of the police, right down to the hapless human rights activists and the big boss himself, it’s like a macabre game from which Loznitsa’s heroine – and we, the viewers, no less – can only hope to wake up.

Except it’s exactly that consolation which the film’s final 40 minutes, a kind of film-within-a-film dream sequence, denies us, presenting instead a highly stylised parodic riff on the rituals of Soviet society, a set piece with a high sense of theatre that contrasts abruptly with the grotesque confusion of what has come before. I’m not certain that it convinces completely, at least not for viewers for whom the original iconography isn’t immediately recognisable, but it allows Loznitsa to build to closing scenes of unmatched, sickening cruelty. It’s an experience from which you may well want to flinch, but its cumulative power makes A Gentle Creature Loznitsa’s most substantial achievement to date, certainly in the scale of his vision. Whether the accompanying reduction in subtlety counts as a loss too far is another matter, as is whether this is a sheer too-wilful darkness (that distinctive Russian concept of chernukha) rather than anything more considered. More perversely, does the film’s total absorption in its strongly defined stylistics, its “performance” manner, even somehow qualify any immediate “message”?

It’s an experience from which you may well want to flinch, but its cumulative power makes A Gentle Creature Loznitsa’s most substantial achievement to date, certainly in the scale of his vision. Whether the accompanying reduction in subtlety counts as a loss too far is another matter, as is whether this is a sheer too-wilful darkness (that distinctive Russian concept of chernukha) rather than anything more considered. More perversely, does the film’s total absorption in its strongly defined stylistics, its “performance” manner, even somehow qualify any immediate “message”?

But, as Lozntisa says at the beginning of a substantial July 2017 filmed interview that is the main extra here, the important thing is “to ask questions”, to disconcert. He’s revealing on a range of topics, including his collaborative approach to work with his regular crew, principal among whom is Romanian cinematographer Oleg Mutu (who certainly works across a broad, often painterly canvas here); there’s lively discussion of the interrelation between his documentary and fiction work, too. Rounding out this excellent Arrow Academy release is a video appreciation from film historian Peter Hames on Lozntisa’s career to date, together with a booklet essay by critic Jonathan Romney, and a trenchant print interview from the director that accompanied his Cannes premiere. Like the remarkable faces of his protagonists, A Gentle Creature is an unforgiving – and unforgiven – experience, and the sheer bravura of its achievement offers scant final consolation. Disconcert, Lozntisa certainly does.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for A Gentle Creature

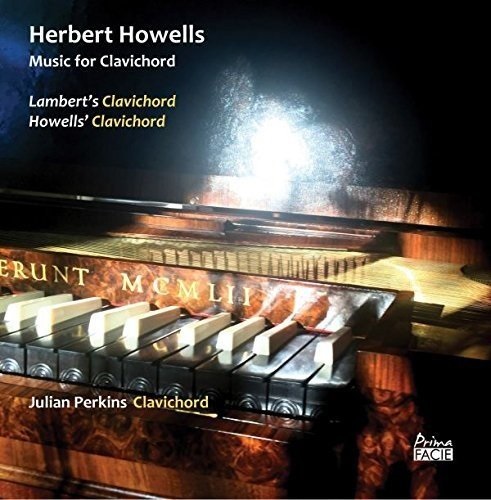

Herbert Howells: Music for Clavichord Julian Perkins (Prima Facie)

Herbert Howells: Music for Clavichord Julian Perkins (Prima Facie)