It's tempting to say that Martin Scorsese's first so-called "family film" works like clockwork, except that the movie possesses considerably more soul than that statement suggests. What's more, it would help to be a clan of thoroughgoing cinéastes to tap entirely into its charms, as a director steeped in the history of his chosen medium takes us backwards in time towards the very origins of the art form he so reveres. Kids may love the sweep and scope of the visuals, many of them involving timepieces that whir and tick and hum, but Hugo at heart is an extended act of homage toward the miracle that is celluloid itself. Those on Scorsese's palpably appreciative wavelength are sure to return his affection in kind.

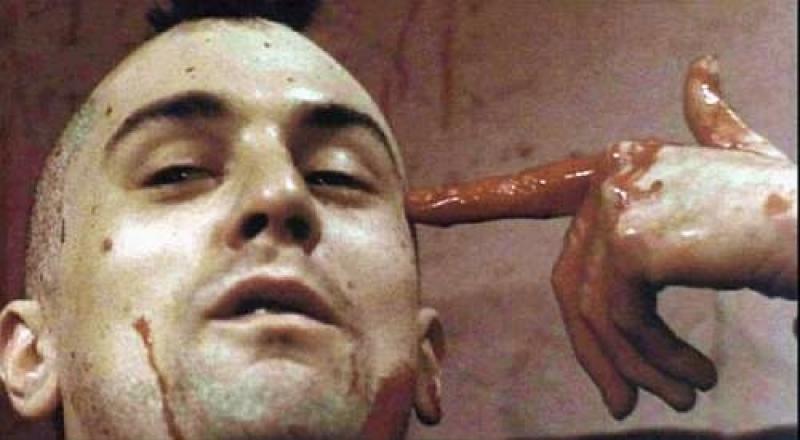

For much of its first hour or so, some may wonder whether this is a Scorsese film at all, given the absence of the raw aggression and rage that have marked out so many of his best films. As the camera of the great cinematographer Robert Richardson swoops around and about a Parisian railway station some 70 years ago, an extravagant landscape emerges packed with mechanised instruments, gears and watch faces of all shapes and sizes. The human element includes Richard Griffiths and Frances de la Tour as putative lovers along with a maniacal station inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen, pictured below with the film's two young leads) whose black Doberman keeps shooting out of the screen toward us as befits a film shot, rapturously, in 3D: all more Spielberg, surely, than Scorsese?

There's a whiff of Spielberg, too, in the presence of an orphaned boy driving the narrative, and not only because Hugo star Asa Butterfield at times looks disconcertingly like the hero, Tintin, at the heart of that other 3D venture of late (well, minus the quiff). With the height and breadth of the Gare Montparnasse as his playground, Butterfield's shining-eyed Hugo sets about on a mission to put right a broken automaton that was a favourite object of the boy's late father - that role played in a notably warm cameo by Jude Law, who brings real feeling to scant amounts of screen time.

There's a whiff of Spielberg, too, in the presence of an orphaned boy driving the narrative, and not only because Hugo star Asa Butterfield at times looks disconcertingly like the hero, Tintin, at the heart of that other 3D venture of late (well, minus the quiff). With the height and breadth of the Gare Montparnasse as his playground, Butterfield's shining-eyed Hugo sets about on a mission to put right a broken automaton that was a favourite object of the boy's late father - that role played in a notably warm cameo by Jude Law, who brings real feeling to scant amounts of screen time.

Hugo's quest involves locating the key to a heart-shaped lock, a task that leads him to a bookish girl called Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz, giving the only stiff performance of the film) who uses Cyrano-ish words like "panache" and has a crank of a guardian (Ben Kingsley), a toy store proprietor whose apparent identity gives no sense of his one-time renown. At snarling odds with humankind (and, we discover, with his own past), Isabelle's Pappa Georges needs nothing more than to have his own heart reopened, which Hugo and Isabelle are eventually able to do. Who, in fact, is this ageing scold? No less a legendary figure than Georges Méliès, the celluloid visionary (1861-1938) without whose genius such devoted practitioners and scholars of the form as Scorsese would have had no career.

It's at this point that Hugo goes its own singular way, Scorsese increasingly limiting the comic freneticism of an eyebrow-heavy Baron Cohen in hot pursuit of his pre-teen prey so as to give time to an extended history lesson about the movies, complete with a recreation of the Lumière brothers' 1897 Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat that is seen to inform both Hugo's sleeping and waking selves. Effecting his own rehabilitation of the life and work of Méliès, the latter now largely lost to us, Scorsese moves beyond the academicism embodied on screen by Broadway actor Michael Stuhlbarg's professorial Tabard to proffer a story of rebirth and renewal that works on multiple levels. Even better, the emotions are informed at every turn by visuals that suggest a dizzying hybrid of Harold Lloyd (whose silent 1923 classic Safety Last is specifically referenced), Chaplin's Modern Times and the Sophie Treadwell play Machinal.

The scenes devoted to Méliès's artistry further the screenwriter John Logan's interest in the artistic process as evidenced previously in his London and Broadway hit play, Red, while at the same time reminding us of Scorsese's championing over time of the work of Pressburger and Powell and of his crusading work as a film preservationist - which is to say that Hugo ricochets well beyond the parameters of its narrative, as one might expect from the talents involved. The automaton (pictured above, as Butterfield looks up in awe) is a red herring given a venture that is deeply humane.

The scenes devoted to Méliès's artistry further the screenwriter John Logan's interest in the artistic process as evidenced previously in his London and Broadway hit play, Red, while at the same time reminding us of Scorsese's championing over time of the work of Pressburger and Powell and of his crusading work as a film preservationist - which is to say that Hugo ricochets well beyond the parameters of its narrative, as one might expect from the talents involved. The automaton (pictured above, as Butterfield looks up in awe) is a red herring given a venture that is deeply humane.

You could argue that the film sometimes gets a bit gushy ("come and dream with me" goes an exhortation revisited in varying soundbites during the last reel or two), rather in the manner of those sonorous voiceovers we hear at places like the Oscars, at which point the tuxedoed assemblage turns all dewy-eyed. But there's nothing remotely faux about a movie that eats, sleeps and breathes the cinema and invites viewers to do the same. How will such passions square with a filmgoing community today that is more acclimatised to the likes of (God forbid) rival 3D entry Immortals? Well, Scorsese was eight when he saw The Red Shoes, and look what happened there. Or, to co-opt the language of Hugo, when it comes to this film's possible imprint upon its audience, one can only dream.

MORE MARTIN SCORSESE ON THEARTSDESK

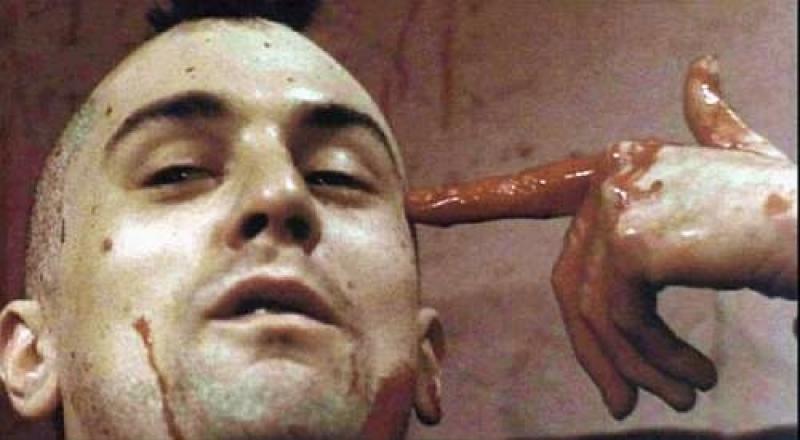

Taxi Driver (1976). Talking to me? Scorsese's classic starring Robert De Niro (pictured) is restored and re-released on its 35th anniversary

Taxi Driver (1976). Talking to me? Scorsese's classic starring Robert De Niro (pictured) is restored and re-released on its 35th anniversary

Shutter Island (2010). Not a blinder: Leonardo DiCaprio in Martin Scorsese's feverish paranoid thriller

George Harrison - Living in the Material World (2011). Martin Scorsese's epic documentary of the Quiet One

The Wolf of Wall Street (2014). Con brio: Scorsese and DiCaprio tell of the rise and fall of a broker

Arena: The 50 Year Argument (2014). A warmly engaging film about the 'New York Review of Books' might have been more than a birthday love-in

Vinyl (2016). Scorsese and Jagger's series is prone to warping, skipping and scratches

Silence (2016). Scorsese's latest is a mammoth, more ponderous than profound

Overleaf: Watch the trailer for Hugo

There's a whiff of Spielberg, too, in the presence of an orphaned boy driving the narrative, and not only because Hugo star Asa Butterfield at times looks disconcertingly like the hero,

There's a whiff of Spielberg, too, in the presence of an orphaned boy driving the narrative, and not only because Hugo star Asa Butterfield at times looks disconcertingly like the hero,  The scenes devoted to

The scenes devoted to

Among the joys the film affords is the way it gives

Among the joys the film affords is the way it gives

However, although screenwriters

However, although screenwriters