Gurinder Chadha is still best-known for directing a low-budget comedy set in Hounslow about two girls who just want to play football. Bend It Like Beckham (2002) introduced Keira Knightley and in 2015 became a stage musical that lured Asian audiences to the West End. While she also explored British Asian culture in Bride and Prejudice (2004) and It’s a Wonderful Afterlife (2010), in her new film she abandons light comedy to address the biggest and most decisive moment in Britain’s relationship with India.

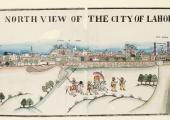

Viceroy’s House is set in 1947 at the moment Lord Mountbatten arrived in Delhi to oversee the handover of India to its own people. Independence turned out to mean partitioning the country along religious lines, resulting in the migration of 14 million refugees across newly created borders. Among those migrants were Chadha’s paternal grandparents, who left their home in what became Pakistan. (The migration continued: in 1960 Chadha was born in Kenya and grew up in Southall, west London).

The film features the Mountbattens, played by Hugh Bonneville and Gillian Anderson, and the politicians arguing over the rights and wrongs of Partition. But it also dramatises the lives of the indigenous staff working in the eponymous palace, among them a young Muslim translator (Huma Qureshi) and a Hindu security guard (Manish Dayal) who fall in love across the religious divide. Viceroy’s House is a darker film than anything Chadha and her co-scriptwriter Paul Mayeda Burges have made before – lest we forget, she once directed Angus, Thongs and Perfect Snogging. It’s much more sumptuous to look at too. She tells theartsdesk what drew her to the material after avoiding it for many years.

JASPER REES: Why did you shun this story inspired by your family history for so long?

GURINDER CHADHA (pictured right on set with Om Puri): I just didn’t really have the courage. It’s a very sad part of my background. It was a very turbulent moment in our shared history, British and Indian, and there were a lot of people with very strong feelings about it and I just didn’t know if I could tell that story. It was only when I went to Pakistan for the first time to my ancestral town with Who Do You Think You Are? that I received such a warm welcome and really felt for the people who had moved into my grandfather’s house where my grandmother had left as a refugee in 1947. There were now five families who had moved in as refugees themselves. So I felt at that point that I really should do something on the Partition but from the people’s perspective.

GURINDER CHADHA (pictured right on set with Om Puri): I just didn’t really have the courage. It’s a very sad part of my background. It was a very turbulent moment in our shared history, British and Indian, and there were a lot of people with very strong feelings about it and I just didn’t know if I could tell that story. It was only when I went to Pakistan for the first time to my ancestral town with Who Do You Think You Are? that I received such a warm welcome and really felt for the people who had moved into my grandfather’s house where my grandmother had left as a refugee in 1947. There were now five families who had moved in as refugees themselves. So I felt at that point that I really should do something on the Partition but from the people’s perspective.

A lot of people don’t know anything about this history - they don’t even know that Partition happened. I had to get a lot of information in in a way that would feel like proper storytelling. Then I got the idea to do it as an upstairs downstairs story – long before Downton Abbey happened. I wanted to tell the political story about Mountbatten negotiating with the leaders, but at the same time I wanted to see the effects of the decisions being taken upstairs on the ordinary people downstairs so I needed to build up the relationships with Mountbatten’s butler and valet and the translator and the chefs (see clip below).

The film is appearing at another moment of mass migration. Does that give the film extra impetus?

Absolutely. When we were shooting one of the refugee scenes I had 1,000 extras in a fort in Rajastan. That morning was the day the little Syrian boy’s body had been found washed up on a beach. We were at the height of the Syrian refugee crisis. Every day we’d see that on the news and on our phones but then go out and shoot refugees in the film.

And how it might land on a cinema-going audience?

We live at a time where people are trying to divide us instead of looking at real issues of unemployment and economic stability for ordinary working people. I think that what the film really does is provide a timely reminder of what can happen when you start scapegoating different groups and how quickly that can escalate into terrible violence and death. It can just happen overnight. And that’s what happened in 1947.

You have a fictional relationship at the heart of the film between a Muslim woman and Hindu man, and there’s a lot of dialogue between the Mountbattens and their Indian staff. Did you feel that, in order to animate the canvas, characters had to speak to one another in a way they possibly mightn’t have in reality?

Absolutely, I was looking for interactions between the upstairs and downstairs. I was looking for what would have been real. Mountbatten banging on about his medals and the order in which he liked to get dressed – all that is very real and based on interviews with people who were there at the time. And yes we did fictionalise the downstairs characters but in many ways they represented people out there at the time – Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs – who all had to make decisions about their future. Doing it through a love story was a very accessible way to show that (see clip below).

This is not a film about giving the British a bloody nose. Was that very deliberate?

This is a film 70 years later looking at the lessons we can learn from events and how the geopolitics at the time unfolded and how can we be aware of those sacrifices that people made then and make sure that we don’t walk into the same trap today. I think Britain is ready to go back and look at some of our shared British Asian history of the Raj but not from the point of giving a bloody nose but saying, this was a policy at the time, these were our interests, and these were Pakistanis’ interests and these were India’s interests. Fourteen million became refugees overnight. What are we doing today when those things can happen again? We’d better watch ourselves

Was it very deliberate that you went in Hugh Bonneville for an extremely likeable Mountbatten?

Yes because Mountbatten actually was likeable and very charming but not particularly astute as a politician, unlike his wife. I felt that Hugh conveys that. He’s very charming and you want to have a drink with him but do you want him to be ruling over your country? I don’t think so. You’ve avoided any hint of an affair between Nehru and Edwina. Why? (Pictured above: Gillian Anderson and Tanveer Ghani)

You’ve avoided any hint of an affair between Nehru and Edwina. Why? (Pictured above: Gillian Anderson and Tanveer Ghani)

I didn’t avoid it. I show them sitting quite intimately with looks towards each other. I show they’re very comfortable with each other’s company and that there is an intimacy there. What I didn’t choose to do was bang on about a relationship because I thought that took away from the story that was important to me, the political story but also the ordinary people. For me it was more important to tell the love story downstairs.

What did you carry away from David Lean’s A Passage to India and Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi and perhaps The Jewel in the Crown as well?

These are all films that were part of my education on the British Raj. Gandhi was a searingly important film for me. It was on an epic scale. It was a massive event for us as a community. The Jewel in the Crown of course did attempt to look at the role of the British in India in a different way. All these films have been part of my film education which is precisely why I wanted to set Viceroy’s House up as a sumptuous British Raj costume epic and then start subverting it by focusing on characters who might not have had the importance in other films. Having a foot in both communities I’m able to straddle both sides and hopefully tell you the story from a different perspective. What would you have done in 1947 if you’d been in charge?

What would you have done in 1947 if you’d been in charge?

Oh my lord. Well I certainly would not have agreed with Mountbatten bringing the date forward. If I had been in charge I would have had more people on the ground listening to what was going on and planned for transition better. But ultimately, I probably would have kept it as one country but made sure that the Muslim minority felt protected.

Did you grandparents end up living in the UK?

No. After my grandfather had spent 18 months looking for my grandmother and the children, he then took them all to Kenya. They had businesses there and they used to go back and forth from India to Kenya. Later my grandfather built another big building in India which is still there but somehow I just don’t feel connected to it. Sadly I never met either of these grandparents and these are stories I was told through their children. I knew my maternal grandmother. She came to live with us, and she had lots of horror stories to tell of that time. I’m told by a friend of mine who is a psychic that my grandfather walks with me. He saw a picture of him and said, "He’s always there standing with you." That's a bit of a freaky comment but at the same time I do take comfort from it.

- Viceroy's House opens on Friday 3 March

Overleaf: watch the trailer to Viceroy's House

For budgetary reasons these larger events happen off camera or in newsreels, but the house itself is not cut off from the wider context. The liveried servants, the staff in the kitchen, the guards all have an urgent need to know what’s happening in the negotiations. Some yearn for an independent Muslim state, others are passionate for India to remain whole. Thus there’s a good deal of listening at keyholes and through cracks in doors.Chadha’s script, written with Paul Mayeda Berges, dramatises a nation’s agony in a story of thwarted love between two members of staff. Jeet Kumar, who is Hindu, falls for Aalia (Manish Dayal and Huma Qureshi, pictured above), the daughter of a former Muslim political prisoner (Om Puri). The problem is that Aalia is betrothed to one of her own, a soldier who hasn’t returned from the war. In the palace compound where they live tensions rise between communities, until the Muslim housing is torched.

For budgetary reasons these larger events happen off camera or in newsreels, but the house itself is not cut off from the wider context. The liveried servants, the staff in the kitchen, the guards all have an urgent need to know what’s happening in the negotiations. Some yearn for an independent Muslim state, others are passionate for India to remain whole. Thus there’s a good deal of listening at keyholes and through cracks in doors.Chadha’s script, written with Paul Mayeda Berges, dramatises a nation’s agony in a story of thwarted love between two members of staff. Jeet Kumar, who is Hindu, falls for Aalia (Manish Dayal and Huma Qureshi, pictured above), the daughter of a former Muslim political prisoner (Om Puri). The problem is that Aalia is betrothed to one of her own, a soldier who hasn’t returned from the war. In the palace compound where they live tensions rise between communities, until the Muslim housing is torched. The film is very handsome to look at, and Chadha’s funny bones lay on plenty of light entertainment. But the laughs – and the sumptuous production values - feel like a sleight of hand distracting from the greater tragedy of India’s unseen agonies, which are mainly reported in dialogue between the higher-ups. Britain also gets a bit of a free pass as the architect of Partition. It falls to Michael Gambon as General Hastings Lionel Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay, KG, GCB, CH, DSO, PC, DL - "Pug" to his chums - to embody the nastier side of British realpolitik, while the Mountbatten family unit – and by implication the British establishment as a whole – is portrayed in the most flattering light.

The film is very handsome to look at, and Chadha’s funny bones lay on plenty of light entertainment. But the laughs – and the sumptuous production values - feel like a sleight of hand distracting from the greater tragedy of India’s unseen agonies, which are mainly reported in dialogue between the higher-ups. Britain also gets a bit of a free pass as the architect of Partition. It falls to Michael Gambon as General Hastings Lionel Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay, KG, GCB, CH, DSO, PC, DL - "Pug" to his chums - to embody the nastier side of British realpolitik, while the Mountbatten family unit – and by implication the British establishment as a whole – is portrayed in the most flattering light.

GURINDER CHADHA (pictured right on set with Om Puri): I just didn’t really have the courage. It’s a very sad part of my background. It was a very turbulent moment in our shared history, British and Indian, and there were a lot of people with very strong feelings about it and I just didn’t know if I could tell that story. It was only when I went to Pakistan for the first time to my ancestral town with Who Do You Think You Are? that I received such a warm welcome and really felt for the people who had moved into my grandfather’s house where my grandmother had left as a refugee in 1947. There were now five families who had moved in as refugees themselves. So I felt at that point that I really should do something on the Partition but from the people’s perspective.

GURINDER CHADHA (pictured right on set with Om Puri): I just didn’t really have the courage. It’s a very sad part of my background. It was a very turbulent moment in our shared history, British and Indian, and there were a lot of people with very strong feelings about it and I just didn’t know if I could tell that story. It was only when I went to Pakistan for the first time to my ancestral town with Who Do You Think You Are? that I received such a warm welcome and really felt for the people who had moved into my grandfather’s house where my grandmother had left as a refugee in 1947. There were now five families who had moved in as refugees themselves. So I felt at that point that I really should do something on the Partition but from the people’s perspective. You’ve avoided any hint of an affair between Nehru and Edwina. Why? (Pictured above: Gillian Anderson and Tanveer Ghani)

You’ve avoided any hint of an affair between Nehru and Edwina. Why? (Pictured above: Gillian Anderson and Tanveer Ghani) What would you have done in 1947 if you’d been in charge?

What would you have done in 1947 if you’d been in charge?

When all attempts to resolve the mystery of where he has come from fail, Saroo is chosen for international adoption, and his next removal is to Tasmania, to his new parents Sue and John Brierley (Nicole Kidman, David Wenham). After the aridity and tumult of India, this Australian landscape is an open one, dominated by water, every bit as unfamiliar to Saroo as the refrigerator and television in his new home. Pawar conveys a wide-eyed, silent wonder as he discovers it all, and he’s anchored by Sue's unquestioning presence. There’s nothing glamorous about Kidman (pictured above with Pawar) – even for late-80s Tasmania she seems almost determinedly plain – but she’s translucently sure of herself, emanating a stillness that captures the screen. It’s an assurance that will be tested with the arrival of the couple’s second adopted son, Mantosh, clearly damaged by his experience in a way that Saroo has avoided.

When all attempts to resolve the mystery of where he has come from fail, Saroo is chosen for international adoption, and his next removal is to Tasmania, to his new parents Sue and John Brierley (Nicole Kidman, David Wenham). After the aridity and tumult of India, this Australian landscape is an open one, dominated by water, every bit as unfamiliar to Saroo as the refrigerator and television in his new home. Pawar conveys a wide-eyed, silent wonder as he discovers it all, and he’s anchored by Sue's unquestioning presence. There’s nothing glamorous about Kidman (pictured above with Pawar) – even for late-80s Tasmania she seems almost determinedly plain – but she’s translucently sure of herself, emanating a stillness that captures the screen. It’s an assurance that will be tested with the arrival of the couple’s second adopted son, Mantosh, clearly damaged by his experience in a way that Saroo has avoided. But it’s something else that he learns from them that propels Lion’s denouement. When Saroo opens up about his past, their mention of Google Earth sets him on a new journey, which will both disrupt his Australian life and (no particular spoiler alert) open a new Indian world. That it’s a piece of new technology that sets him out on his journey home may seem at first anomalous – myths normally being made of things other than GPS coordinates and screen images – but there’s no disputing the reality of Saroo’s story: we see its real-life conclusion in the film’s coda.

But it’s something else that he learns from them that propels Lion’s denouement. When Saroo opens up about his past, their mention of Google Earth sets him on a new journey, which will both disrupt his Australian life and (no particular spoiler alert) open a new Indian world. That it’s a piece of new technology that sets him out on his journey home may seem at first anomalous – myths normally being made of things other than GPS coordinates and screen images – but there’s no disputing the reality of Saroo’s story: we see its real-life conclusion in the film’s coda.