Jansen, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Nézet-Séguin, Royal Festival Hall

Prokofiev season concludes with a welcome return to the symphonic mainstream

At last, a bag of sweets! In earlier concerts from Vladimir Jurowski’s LPO series Prokofiev: Man of the People? much time was spent consuming the composer’s flat soufflés, experimental rock cakes, or the fancy dish that was really haddock. Interesting for the brain, maybe, but the diet on occasion has been hard on the stomach. Not that any of this impinged on audience numbers: the season has definitely proved Jurowski’s happy lock on the London Philharmonic’s audiences. They will follow their artistic guru and Principal Conductor almost anywhere.

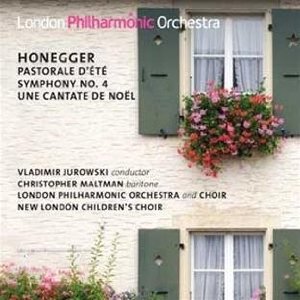

Honegger: Une cantate de Noël, Pastorale d’été, Symphony No 4 London Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir, New London Childrens’ Choir/Jurowski (LPO)

Honegger: Une cantate de Noël, Pastorale d’été, Symphony No 4 London Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir, New London Childrens’ Choir/Jurowski (LPO)