Now at the very top of his game and master of sundry great orchestras around the world, Paavo Järvi is the conductor students of the art like to follow for his perfect technique. Time was when he seemed like the cooler version of his peerless father Neeme; now, if he can still at times come across as more cerebral than his impetuous but also excellent younger brother Kristjan, he often seems touched by the kind of inspiration Neeme maintains in his 80th year.

They work together under Utopian circumstances every summer with the superband Estonian Festival Orchestra and the promising trainees of the Academy Orchestra in the idyllic Estonian seaside town of Pärnu, which is where I’ve spent most time with Paavo and got to know his clubbable ways. We met most recently the morning after the last concert in his Nielsen series at the Royal Festival Hall with the Philharmonia Orchestra, with whom he has a special understanding. Even so, there isn’t the luxury of so much time to work together and their performance of the Sixth Symphony, ironically nicknamed the “Semplice” or “Simple”, while perfect in conception, could have done with a rehearsal or two more to give the Philharmonia strings a chance to blaze. The ethos of the first half, on the other hand, struck me as very rare in London: not just perfect teamwork but a congeniality shared with the audience and communicated, I think, to all - initiated by the conductor in a hyper-elegant Haydn "Clock" Symphony, enhanced in Beethoven's Triple Concerto by the well-bonded trio of violinist Christian Tetzlaff, his cellist sister Tanja and their friend the pianist Lars Vogt.

The upshot of a fine evening attended by most of the musical Estonians in London was a rather too jolly night on the town, so that when I turned up at Paavo’s Notting Hill flat the following morning, there was no answer. After an entertaining 20 minutes with the music-lover who’d steered him home but still couldn’t get a reply any more than I could, he surfaced, very apologetic. Our chat was friendly as always, but rather disrupted by the next arrival, and so this is a snapshot, mostly of impressions from the previous evening, which give some indication of his general approach as drawn from the specific. We moved eventually from the London concert to the prospect of his next appearance here as Chief Conductor of the NHK Symphony Orchestra Tokyo (pictured below by Takao Hashimoto: on the Berlin leg of their tour; Graham Rickson reviews their new Strauss disc in his Classical CDs roundup today).

DAVID NICE: It was quite a shock to be reminded of the horrors of this week [Trumpery and unrest elsewhere] by the explosions of Nielsen’s first movement. I’d forgotten about them completely, transported into that world of lightness and humour you sustained in the first half. I laughed a lot and smiled all the way through the Haydn and the Beethoven Triple Concerto. That was the second late Haydn symphony I've heard you conduct the Philharmonia in - do you think there's a special affinity there?

PAAVO JÄRVI: I think any orchestra that wants to be seen as a serious contender in being a great exponent of the repertoire has to have some kind of familiarity with Haydn. That symphony or any other symphony of his, out of that comes everything else that we are symphonically proud of or impressed by - Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, that is a kind of a blueprint for a symphony. And it's so witty and joyful and everything you need to have in a symphony, including unusual orchestration - and you have this fugue in Nielsen, and before that a fugue in Haydn, and before that... where does it all come from? Nielsen in the 1920s years later shows how far the symphony has come from the basics to the midst of a corrupted world, even if in the "Semplice" it's a world that starts out fine on the surface. Each variation in the finale is corrupted and stripped of its dignity.

In a way that's the Nielsen symphony that should be called the "Inextinguishable", because of the way in the first movement there are endless pile-ups and he just picks himself up and starts again. It's astonishingly modern in its fragmentation and sudden violence, isn't it?

Yes, it gets destroyed and starts up again and again and again. It's interesting that we have this tendency to think of these modernists who changed the world, I'm talking about after Stravinsky, Boulez for example. This piece was written in 1925; nothing that's been created since has come close to the originality and the daring newness of the things he describes.

Could you describe it as post-modernist?

Yes, exactly, but the funny thing is that modernism hasn't happened yet. This is genius.

I've never found any proof that Shostakovich knew Nielsen's Sixth, but I hear direct parallels in the dance sequence of his Fourth Symphony composed a decade later, where he even seems to quote Nielsen's finale in one galop, and in the innocent way - also with a glockenspiel - his Fifteenth Symphony of 1971 begins. What do you think of that possibility?

Maybe he would have seen a score. But I'm not so sure. If you think of people asking, "what is the simplest and purest thing?" the answer has to be that it's a bell. I think it's arriving at the same conclusion. Sometimes scientists arrive at the same conclusion simultaneously from different places. I don't think any one of them would have taken anything. One thing's for sure, both Nielsen and Shostakovich can seem crazy in those works. Sometimes you can be too crazy for people to accept the new. It's a funny thing, I know a lot of violinists who never play the Nielsen Concerto. They play Dutilleux, other 20th-century works. Why not the Nielsen? Somehow at one point teachers say it's not really great music. Of course it is. But they have been taught or convinced that it's not worth their time. At the same time they do play Shostakovich Second.

It's an obligatory work at the Nielsen Competition in Odense, but that's a Danish thing.

Thank God, because at least violinists have experience of doing it – it’s a great concerto. Was it quite hard getting the Philharmonia into shape in a relatively short period of time for playing the "Semplice"? Because the violin writing especially is so hard.

Was it quite hard getting the Philharmonia into shape in a relatively short period of time for playing the "Semplice"? Because the violin writing especially is so hard.

They are so amazing, they're a sensational orchestra, a typical London orchestra where it's every week a new thing to play, it's not important what you play, whether you understand it or not, because there's not time to digest it. An orchestra which plays a Dvořák symphony, it's great, because they know and understand it, whereas if you put something in front of them like this, they will bring all their skill to it, but do they understand what they play? No. But then they're willing, and after a couple of rehearsals you begin to get results.

The responsibility's yours.

Yes, but they're so good and so unbelievably willing. I don't know, I must say I'm incredibly proud that we did all six Nielsen symphonies in London where everything is about box office and attendance, OK we didn't have a sold-out house, but at least there was a sense of proper enjoyment. In other places it would have been empty after the first bar. I think it was also a bit of congratulation, thank you that you did it. I think every Nielsen lover in Britain was there.

What we saw last night is this very genuine communicative rapport, front desk, smiling.

I must say I'm so humbled by the fact that these hardcore, hard-working London musicians, great as they are, and they're not very well paid, but to see them having fun and going for it, that's one of the best things you can imagine, enjoyment in this nightmare of a symphony where you don't know what's going on, nobody can relate to anything technically or rely on anything for a little bit.

The more rehearsals you have the freer you would be.

It's not so much rehearsal but a couple of performances, one or two, before you come to London, because it's like preparing yourself for jumping out of a plane, you can't academically prepare yourself, just jump, and after you go through it, once or twice, it's not about knowing how it is, it's just one of those things you have to have experience of doing, and thank God I had the concert in Stockholm the night before, that is so important. They gave a very good concert, I'm not talking about using them as guinea pigs, but after the first experience the second is an entirely different one.

You know it well.

But they'd never played it. As much as people say, we don't need a conductor or whatever, that's a symphony where they need one. They can do a Haydn by themselves, not as well, but they can. Every variation in Nielsen's finale needs to be conducted with total organisation. I'm glad you liked the swift bringing-in of the fanfares at the end. What else can happen? How weird can we get now? Let's bring in a fanfare. It's genius. There was something special about the performance of the Beethoven Triple Concerto last night (pictured above by Giorgia Bertazzi: Lars Vogt and Tanja and Christian Tetzlaff), would you agree? I've never enjoyed it so much - in fact I've hardly enjoyed it at all before.

There was something special about the performance of the Beethoven Triple Concerto last night (pictured above by Giorgia Bertazzi: Lars Vogt and Tanja and Christian Tetzlaff), would you agree? I've never enjoyed it so much - in fact I've hardly enjoyed it at all before.

Usually what happens is that you have three musicians coming from three different continents coming together and playing. And it sounds OK, but it doesn't sound like anyone knows each other, that they have a concept, that they have had time to work. This is a family. Two of them are siblings and Lars should basically be called their brother - that's how I introduced him, as a joke. I've known them for 20 years. Tanja is principal cellist in the [Deutsche] Kammerphilharmonie [Bremen, where Paavo is Artistic Director], and that's why they have an intimate knowledge of each other, it's one of those things, otherwise everybody starts and it flows along like a stream..

But it's not top-notch Beethoven, is it?

I think it is. That slow movement, if it's really played fully, I think it's moving. If it's just played OK, I agree, it sounds bland. I grew up with teachers telling me it's not as great as the Violin Concerto. Christian Tetzlaff made certain nuances yesterday, little timing things, dramatic things - that made it great music because it was great music-making. As for the orchestra, when you have soloists who are so in tune with each other, it's infectious. You always connect with them.

Your second disc of Strauss with the NHK Symphony Orchestra, which you're bringing to London, has a very special quality about it, a focused, gleaming sound. Did you work hard on that?

Yes, and I believe Ein Heldenleben is a good way of introducing this orchestra. I discussed with my father once how this is a piece about gestures. And the gestures often come out, but half the notes aren't there. Here you hear every note. And this is seriously sophisticated playing. Why do we never find the NHK Symphony Orchestra placed among the top orchestras of the world? It's always Berlin, Amsterdam, Vienna, the Czech Phil. But I would seriously place them among the top five. You know, there's this cliched thinking that oriental musicians lack feeling. I don't think that's true at all. But in any case many of the NHK players studied in western conservatoires, so they come back after some time and they bring those attitudes with them. Besides, there is an extremely strong connection there with the great Austro-German tradition which dates back far further than people think. Wolfgang Sawallisch worked with the NHK a lot, and Karl Böhm was a regular visitor to Japan. (Pictured below by Takao Hashimoto: Paavo coming on stage to conduct the NHK Symphony Orchestra in Berlin) I remember when we first met 30 years ago in Notting Hill, it was still in the days of the fax machine and faxes were coming through from your father discussing recordings you'd both listened to, or recommending performances you must hear. Is the relationship still similar?

I remember when we first met 30 years ago in Notting Hill, it was still in the days of the fax machine and faxes were coming through from your father discussing recordings you'd both listened to, or recommending performances you must hear. Is the relationship still similar?

Oh, it's fantastic. I always get on the phone to him if I have doubts about how a movement should go, or else I try things out with him. He's still my best guide and mentor.

You're at the very top of your game now. Is there anything you want to do that you haven't achieved yet?

I think my schedule is too full - I need to stop going everywhere, it isn't necessary. But I do treasure the relationships I have with my main orchestras and I'm always happy to see them. If I would change anything, it would be to cut down on concert-giving to a degree so that I can concentrate on special projects. You know what we have in Pärnu [with the Estonian Festival Orchestra] - this is something that can't be found anywhere else. I'd hope for more along those lines.

Next page: watch Paavo Järvi conduct the Estonian Festival Orchestra in Nielsen's Second Symphony

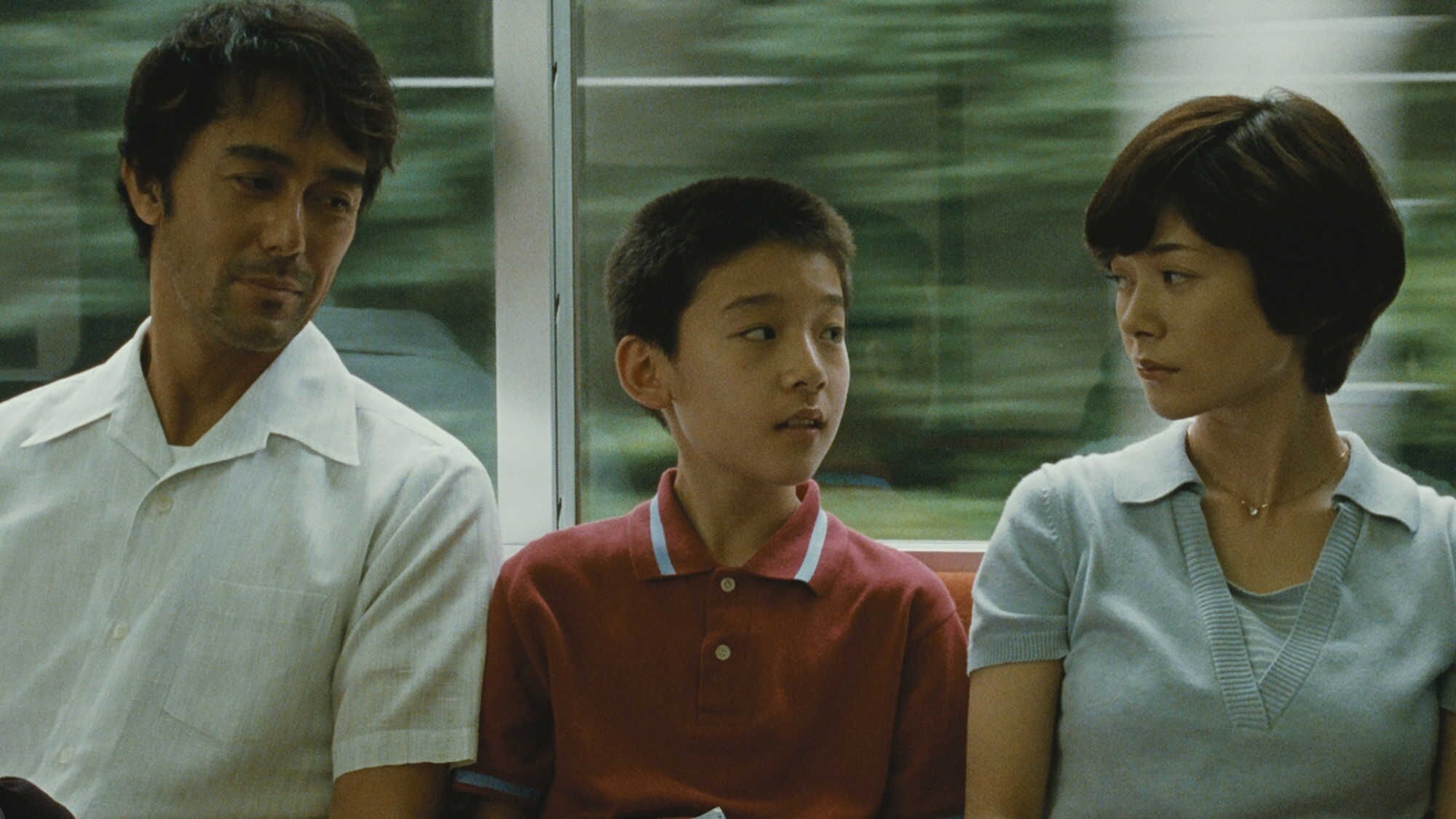

As well as the more mundane tasks of detective work like lost pets, the agency seems to specialise in divorce work, following unfaithful partners for evidence that they are cheating on their marriages, and the like. However, Ryota has made a personal speciality of exploiting such cases for his own ends – he’s an adept at blackmail, or selling incriminating evidence to the guilty party, even shaking down a kid for money to hush up a liaison. Abetted by a fresh-faced colleague, he’s unscrupulous in almost every respect, yet the repercussions of his actions never seem to catch up on him (in a different movie genre, he’d be up making some nasty enemies). He’s doing this, we discover, to feed his longterm gambling habit.

As well as the more mundane tasks of detective work like lost pets, the agency seems to specialise in divorce work, following unfaithful partners for evidence that they are cheating on their marriages, and the like. However, Ryota has made a personal speciality of exploiting such cases for his own ends – he’s an adept at blackmail, or selling incriminating evidence to the guilty party, even shaking down a kid for money to hush up a liaison. Abetted by a fresh-faced colleague, he’s unscrupulous in almost every respect, yet the repercussions of his actions never seem to catch up on him (in a different movie genre, he’d be up making some nasty enemies). He’s doing this, we discover, to feed his longterm gambling habit. It gives rise to a moving denouement, one which even offers hints, however tentative, of hope for the future. Yoshiko may be aware of her encroaching end (“new friends at my age only mean more funerals”), yet hasn’t lost interest in life, even joining a classical music group to discuss Beethoven (she has a soft spot for the teacher, too). Abe’s hangdog face (pictured, top) is an expressive joy in itself, and we somehow can’t help feeling for this undoubted scamp who nevertheless doesn’t seem to mean any harm (“How did my life get so screwed up?” he asks himself). Yoshizawa as the sensitive Shingo beautifully captures the complicated nuances of the child’s love for his unreliable dad, which makes for a loyalty that endures regardless of what he gets up to.

It gives rise to a moving denouement, one which even offers hints, however tentative, of hope for the future. Yoshiko may be aware of her encroaching end (“new friends at my age only mean more funerals”), yet hasn’t lost interest in life, even joining a classical music group to discuss Beethoven (she has a soft spot for the teacher, too). Abe’s hangdog face (pictured, top) is an expressive joy in itself, and we somehow can’t help feeling for this undoubted scamp who nevertheless doesn’t seem to mean any harm (“How did my life get so screwed up?” he asks himself). Yoshizawa as the sensitive Shingo beautifully captures the complicated nuances of the child’s love for his unreliable dad, which makes for a loyalty that endures regardless of what he gets up to.

Over the three decades it has been making films, Studio Ghibli has created its own fantastic universe, populated by magical creatures and quirky humans. Although its films are usually set in

Over the three decades it has been making films, Studio Ghibli has created its own fantastic universe, populated by magical creatures and quirky humans. Although its films are usually set in

Was it quite hard getting the Philharmonia into shape in a relatively short period of time for playing the "Semplice"? Because the violin writing especially is so hard.

Was it quite hard getting the Philharmonia into shape in a relatively short period of time for playing the "Semplice"? Because the violin writing especially is so hard. There was something special about the performance of the Beethoven Triple Concerto last night (pictured above by Giorgia Bertazzi: Lars Vogt and Tanja and Christian Tetzlaff), would you agree? I've never enjoyed it so much - in fact I've hardly enjoyed it at all before.

There was something special about the performance of the Beethoven Triple Concerto last night (pictured above by Giorgia Bertazzi: Lars Vogt and Tanja and Christian Tetzlaff), would you agree? I've never enjoyed it so much - in fact I've hardly enjoyed it at all before.  I remember when we first met 30 years ago in Notting Hill, it was still in the days of the fax machine and faxes were coming through from your father discussing recordings you'd both listened to, or recommending performances you must hear. Is the relationship still similar?

I remember when we first met 30 years ago in Notting Hill, it was still in the days of the fax machine and faxes were coming through from your father discussing recordings you'd both listened to, or recommending performances you must hear. Is the relationship still similar?