“Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves.” I’ve quoted these words by John Berger many, many times. They are in my bloodstream, as it were, since they provided me with an explanation for my experience as a young woman in the world.

The 1972 television series and accompanying book Ways of Seeing from which they came also changed the way people looked at and thought about art. The clarity and conviction of Berger’s observations about how we see and read images cut through the obfuscating waffle which, until then, had passed for art criticism. He made it clear that images are, first and foremost, a means of communication and, as such, they have political and social content as well as aesthetic merit.

Sadly Berger died last January aged 91. The Seasons in Quincy is an affectionate portrait of the man, his ideas and his life in Quincy, the village in the French Haute-Savoie to which he moved in the mid 1970s with his third wife, Beverly. Made by different directors while Berger was still alive, the four films look at various aspects of his life. For anyone wanting a conventional documentary, they will be a frustrating experience; but then it would be hard to do justice to a man whose prolific writings encompass a wide range of topics.  He described himself as a revolutionary story-teller; when awarded the Booker Prize in 1972 he donated half the prize money to the Black Panther Party in Britain. As well as books on Picasso, Spinoza, documentary photography, the Russian emigré Ernst Neizvestny and artists working in the Soviet Union, Berger also wrote novels, short stories, poems and social commentary. His book A Seventh Man: Migrant Workers in Europe (1975), for instance, was informed by his experience of living and working among peasants in the Haute-Savoie. And he broached the subject again in the 1980s trilogy Into Their Labours, this time in novel form.

He described himself as a revolutionary story-teller; when awarded the Booker Prize in 1972 he donated half the prize money to the Black Panther Party in Britain. As well as books on Picasso, Spinoza, documentary photography, the Russian emigré Ernst Neizvestny and artists working in the Soviet Union, Berger also wrote novels, short stories, poems and social commentary. His book A Seventh Man: Migrant Workers in Europe (1975), for instance, was informed by his experience of living and working among peasants in the Haute-Savoie. And he broached the subject again in the 1980s trilogy Into Their Labours, this time in novel form.

Tilda Swinton describes her opening film as “A photograph of a meeting between friends”. She and Berger were both born on 5 November, 34 years apart; this created, says Swinton, “an indissoluble bond of kinship” between them. She visits Berger the week before Christmas for “a catch-up”.

Watching her slice apples for a crumble triggers childhood memories in him of his father, who served on the Western Front in World War One and was awarded the Military Cross, but never spoke of his wartime experiences. It's another thing the pair have in common; despite losing a leg in World War Two, Swinton’s father never mentioned his disability. The decision to keep silent and not hand on experiences from which one’s children might learn prompted Berger to write, “History cannot have its tongue cut out.”

Swinton ends the film with her recipe for apple crumble, which includes the lines: “an apron of apples preferably from one’s own tree, a horse’s cheek of oats, at least one sound finger and thumb for crumbling, a brave amount of ground ginger, an élan of lemon juice, appetite, good company”. Depending on one’s state of mind, the film is either disarmingly intimate or annoyingly self-regarding.

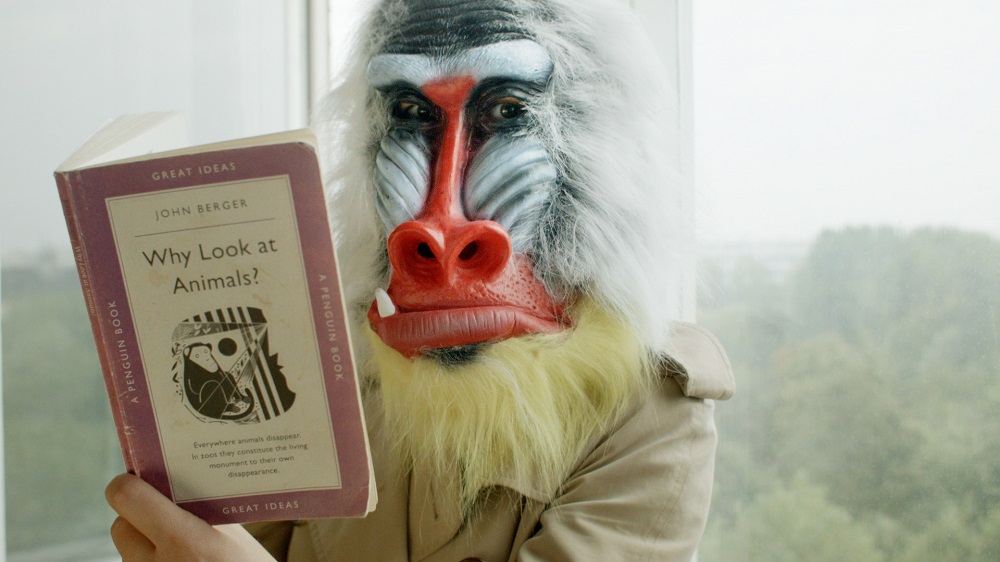

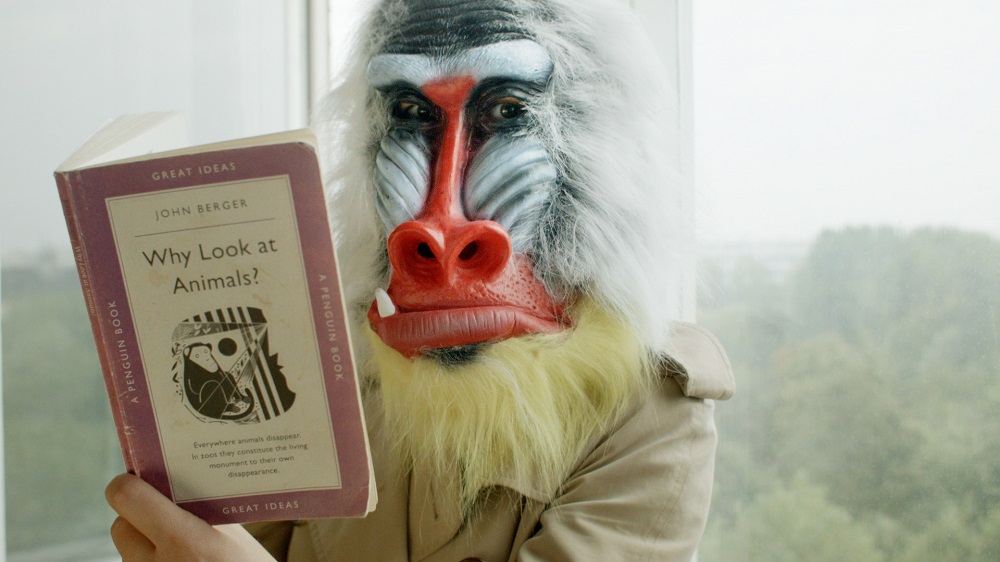

“We came to Quincy to talk to John Berger about uprisings ... the Prague Spring, the Arab Spring and the perpetual false spring of capital,” says Christopher Roth at the beginning of his film Spring. On arrival, though, he discovered that “a private winter had established itself in the household with the death of Beverly”. Switching to plan B, he made a film about animals and our interactions with them. Berger’s presence is established through excerpts from Once Upon a Time, a film made by Mike Dibb in 1983 and extracts from books like Why Look at Animals? and Pig Earth, in which Berger discusses our often conflicted relationship with animals. Footage of zoo and farm animals and an interview with a peasant farmer in Haute Savoie links Berger’s ideas with the present. It is a good film about an important subject, but after the opening statement, it inevitably feels like a stand-in for the main event.

Berger’s presence is established through excerpts from Once Upon a Time, a film made by Mike Dibb in 1983 and extracts from books like Why Look at Animals? and Pig Earth, in which Berger discusses our often conflicted relationship with animals. Footage of zoo and farm animals and an interview with a peasant farmer in Haute Savoie links Berger’s ideas with the present. It is a good film about an important subject, but after the opening statement, it inevitably feels like a stand-in for the main event.

Of the four films, A Song for Politics by Bartek Dziadosz and Colin MacCabe is the nearest thing to a documentary. “All the important decisions which determine the use, exploitation and organisation of the planet and its resources are now taken by financial speculators”, says Berger in a panel discussion about the decline of capitalism and the role of the writer in a world where readers are bombarded by information. This is intercut with snippets from Berger’s many television appearances in the 1960s and ’70s and ends with his affectionate account of arriving in the Haute Savoie. The film cannot hope to be all-encompassing, but it conveys the essence of Berger’s ideas in an extremely engaging and intelligent way.

Continuity is the theme of Harvest by Tilda Swinton. Berger stays with her in Paris, while her children Honor and Xavier travel to Quincy to visit Berger’s son Yves who was born in the village. This euphoric look at his life involves making prints, dipping candles, keeping bees and harvesting raspberries from the canes planted by Beverly, which at John’s request they eat while thinking of her.

Overleaf: watch the trailer to The Seasons in Quincy

The duo becomes an unlikely trio with the appearance, for no particular good reason but very charmingly, of actress Annie (Anne Zelda). Various picaresque dashes around the Edinburgh streets follow, one in a car commandeered from Stephen Frears (credited as “Biscuit Man"). Gallerist Richard Demarco appears somewhat grouchily as himself, Alan Bennett turns in a brilliant cameo as a hilariously diffident doctor who, on being told that writing is a lonely profession, suggests meals on wheels. Susannah York gamely plays along: hearing that the female role is underdeveloped, she coolly replies, “So you came to me?”

The duo becomes an unlikely trio with the appearance, for no particular good reason but very charmingly, of actress Annie (Anne Zelda). Various picaresque dashes around the Edinburgh streets follow, one in a car commandeered from Stephen Frears (credited as “Biscuit Man"). Gallerist Richard Demarco appears somewhat grouchily as himself, Alan Bennett turns in a brilliant cameo as a hilariously diffident doctor who, on being told that writing is a lonely profession, suggests meals on wheels. Susannah York gamely plays along: hearing that the female role is underdeveloped, she coolly replies, “So you came to me?” He described himself as a revolutionary story-teller; when awarded the Booker Prize in 1972 he donated half the prize money to the Black Panther Party in Britain. As well as books on Picasso, Spinoza, documentary photography, the Russian emigré Ernst Neizvestny and artists working in the Soviet Union, Berger also wrote novels, short stories, poems and social commentary. His book A Seventh Man: Migrant Workers in Europe (1975), for instance, was informed by his experience of living and working among peasants in the Haute-Savoie. And he broached the subject again in the 1980s trilogy Into Their Labours, this time in novel form.

He described himself as a revolutionary story-teller; when awarded the Booker Prize in 1972 he donated half the prize money to the Black Panther Party in Britain. As well as books on Picasso, Spinoza, documentary photography, the Russian emigré Ernst Neizvestny and artists working in the Soviet Union, Berger also wrote novels, short stories, poems and social commentary. His book A Seventh Man: Migrant Workers in Europe (1975), for instance, was informed by his experience of living and working among peasants in the Haute-Savoie. And he broached the subject again in the 1980s trilogy Into Their Labours, this time in novel form. Berger’s presence is established through excerpts from Once Upon a Time, a film made by Mike Dibb in 1983 and extracts from books like Why Look at Animals? and Pig Earth, in which Berger discusses our often conflicted relationship with animals. Footage of zoo and farm animals and an interview with a peasant farmer in Haute Savoie links Berger’s ideas with the present. It is a good film about an important subject, but after the opening statement, it inevitably feels like a stand-in for the main event.

Berger’s presence is established through excerpts from Once Upon a Time, a film made by Mike Dibb in 1983 and extracts from books like Why Look at Animals? and Pig Earth, in which Berger discusses our often conflicted relationship with animals. Footage of zoo and farm animals and an interview with a peasant farmer in Haute Savoie links Berger’s ideas with the present. It is a good film about an important subject, but after the opening statement, it inevitably feels like a stand-in for the main event. Roman Ferber, the youngest survivor on Schindler's list, gives a very vivid account of losing his father and brother. We meet him as a soft-spoken man living in America; he shows us images from the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945. Ferber holds up

Roman Ferber, the youngest survivor on Schindler's list, gives a very vivid account of losing his father and brother. We meet him as a soft-spoken man living in America; he shows us images from the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945. Ferber holds up