Artist Tyler Mallison: 'I don’t think about materials as being merely visible objects or things'

Technology as material, Madonna as muse: the artist talks about the themes shaping his current exhibition

Artist and curator Tyler Mallison has chosen the world’s most generic title for his current exhibition. It's called New Material, and the surprising thing one discovers is that the hackneyed "new" really can be quite fresh. Sculpture and painting comprise display units, work desks, gym equipment, packing tape and whitewash. Several films feature window dressing, cross-dressing and gallery furniture.

Fourth Plinth: How London Created the Smallest Sculpture Park in the World

Celebrating Trafalgar Square's infamous empty plinth, and its role in changing attitudes to contemporary art

I have always felt very lucky to have been working as an artist in London during the period when it transformed into the capital of the art world. It has been a beautiful, fascinating and profitable ride. When I started art school in 1978, contemporary art in Britain seemed like a cottage industry situated in some little backwater seldom visited by the public or the media.

French Touch, Red Gallery

Ground-breaking exhibition digs into the history of French electronic music

Un Voyage Á Travers Dans Le Paysage Électronique Français, the French subtitle, goes further. French Touch is the first exhibition to celebrate and dig into France’s electronic music heritage: exploring the lineage which laid the ground for the world-wide success of Daft Punk.

Michelangelo & Sebastiano, National Gallery

Exceptional loans redeem poor display in a tale of two Renaissance masters

The story of two characters whose friendship ended in bitter enmity is juicy enough for a typical spring blockbuster and yet this is an exhibition with a serious and scholarly bent. While the National Gallery is no stranger to academic exhibitions they are usually relatively low-key, occupying the small space of the Sunley Room, for which this exhibition feels as if it might originally have been conceived.

The American Dream: Pop to the Present, British Museum

Sixty years of print-making makes for a thrilling all-American portrait

Dream or nightmare? Bay of Pigs, assassinations, Vietnam, space race, Cold War, civil rights, AIDS, legalised abortions, same-sex marriage, ups, downs and inside outs. From JFK to The Donald in just under 60 years, as seen in 200 prints in all kinds of techniques and sizes by several score American artists (although, shush, a handful are – shock, horror – immigrants).

theartsdesk in Oslo: Mozart beneath a Munch sun

A great Norwegian pianist and a live-wire chamber orchestra collaborate with fresh results

Leif Ove Andsnes directing two great Mozart piano concertos from the keyboard may be the chief attraction when the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra comes to London's Cadogan Hall on Friday to celebrate its 40th birthday. It was certainly the bait which lured me to Oslo last week. But in talking to the Renaissance man who has led the ensemble since its foundation in 1977, Terje Tønnesen, I discovered that what I heard – including a Haydn symphony just as revelatory as the Mozart concertos – was just the tip of the creative iceberg. Londoners will get a greater slice of that individuality when the NCO play Prokofiev's "Classical" Symphony and Grieg's Holberg Suite from memory.

I found out more from Tønnesen the morning after the concert. Which in itself was predictably excellent, but brought a surprise of a different kind. Having admired Edvard Munch's The Sun on the box cover of an LP set featuring Schoenberg's Gurrelieder, I'd wondered where it was housed. I had no idea it was the centrepiece, the high altar, as it were, of a mural series in Oslo's main temple of learning, the University Aula where the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra gives the majority of its concerts on home territory.

The sun glints in the distance as you approach through the vestibule (pictured above). Once entering the hall itself between the columns, two more large-scale scenes complement the al fresco idyll, clearly set on the Norwegian coast with its rocks and islets in midsummer: on the left, "History" is celebrated by an old man telling stories to a young boy, while "Alma Mater" on the right has a mother nourishing her children. Further panels celebrate naked youth in the sunshine. Predictably there was uproar among the academic worthies, and the unveiling didn't take place until 1916, seven years after Munch was announced the winner of the university competition to decorate the aula.

The sun glints in the distance as you approach through the vestibule (pictured above). Once entering the hall itself between the columns, two more large-scale scenes complement the al fresco idyll, clearly set on the Norwegian coast with its rocks and islets in midsummer: on the left, "History" is celebrated by an old man telling stories to a young boy, while "Alma Mater" on the right has a mother nourishing her children. Further panels celebrate naked youth in the sunshine. Predictably there was uproar among the academic worthies, and the unveiling didn't take place until 1916, seven years after Munch was announced the winner of the university competition to decorate the aula.

These are joyous scenes for Munch, unfairly labelled a miserabilist; at the time of painting them he had just emerged from confinement in a Copenhagen psychiatric clinic, positive and full of life. They couldn't help but inform the more joyous of the scores on last week's second Aula programme, chiefly Mozart's K482 E flat Piano Concerto, and Haydn's Symphony No. 95. The mystery of the most recent work on the programme, Norwegian composer Magnar Åm's 1977 tone-poem Study of a Psalm Melody from Luster, was also in tune with the great outdoors pictured above it.

Andsnes' relationship with the NCO goes back a long way. The ensemble's status as a self-styled "project orchestra" gathering together many of Norway's finest instrumentalists for intensive periods of work and touring has included invitations to serve as guest artistic leader to the likes of Steven Isserlis, Isabelle van Keulen and Anthony Marwood, and of course Andsnes, who over five seasons performed some of the greatest Mozart concertos, followed by the five Beethovens in the warm surroundings of the Norwegian National Opera, interpretations we know well from his visit to the Proms with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra.

Now he's added two more to the Mozart list. As he told me over tea before the concert (rehearsal pictured above), “This is a completely different story for me. The D minor [K466] was the first concerto I played with a professional orchestra, in Stavanger when I was 14, and it's always been part of my life, so now it’s like coming back to an old friend. Whereas the E flat is completely new to me, I played it for the first time two weeks ago, and I'm so in love with it.” We talk about the extraordinary finale, its lively rondo coming to a halt to accommodate a heaven-sent, woodwind-led slow serenade of a minuet. “It's so operatic and so like a farewell towards the end. It must have been his own 'Jeunehomme' Concerto [No. 9], the earliest of the three E flat concertos, which inspired the pattern of that grand finale.”

Now he's added two more to the Mozart list. As he told me over tea before the concert (rehearsal pictured above), “This is a completely different story for me. The D minor [K466] was the first concerto I played with a professional orchestra, in Stavanger when I was 14, and it's always been part of my life, so now it’s like coming back to an old friend. Whereas the E flat is completely new to me, I played it for the first time two weeks ago, and I'm so in love with it.” We talk about the extraordinary finale, its lively rondo coming to a halt to accommodate a heaven-sent, woodwind-led slow serenade of a minuet. “It's so operatic and so like a farewell towards the end. It must have been his own 'Jeunehomme' Concerto [No. 9], the earliest of the three E flat concertos, which inspired the pattern of that grand finale.”

I wondered whether intense study of the Beethoven concertos had changed anything. “It’s difficult to say. Of course the D minor is quite Beethovenian, the one he admired the most, and loved very much. And I’m playing Beethoven’s cadenza in the first movement, Hummel’s in the finale. What I felt during those years with Beethoven was how important it is to express things really clearly, because the intention is so clear all the time, and of course in Mozart there is more ambiguity. In the first movement of the E flat concerto, for instance, when I started to study it, I realised it’s not clear what is foreground and what is background [he sings a legato line for the winds, and another for the violins] – it's just a web. It's very fascinating, you can choose what to emphasise, but both are actually equally important, and that's what is so great, that you have these voices. But it's still important to be understood, so maybe I bring with me some of that. Whether that has to do with Beethoven or whether I'm becoming more confident with this music as a whole, I don't know.”

As both musician and as human being, Andsnes never does flash, never comes out with an insincere word. His pianism flowed out of the orchestral playing he conducted and back again, with that legendary evenness in fast runs, only dominating in the cadenzas. I'm not sure that the one in the first movement of the E flat major was entirely organic within itself – Andsnes hadn’t found a cadenza that suited him, and went along with the work of his EMI producer John Fraser, of which he’s very fond – but Beethoven's for the D minor was magnificent on its own terms. And in any case the orchestral playing, especially in the finale, was meatier, more Beethoven-like than you'd expect from a chamber orchestra playing Mozart. With, of course, wonderful work from the woodwind – exceptionally so from first oboist, Mizuho Yoshii, who somehow managed to make us forget that there weren't clarinets, the real stars of the concertos featuring them, in the D minor work.

As both musician and as human being, Andsnes never does flash, never comes out with an insincere word. His pianism flowed out of the orchestral playing he conducted and back again, with that legendary evenness in fast runs, only dominating in the cadenzas. I'm not sure that the one in the first movement of the E flat major was entirely organic within itself – Andsnes hadn’t found a cadenza that suited him, and went along with the work of his EMI producer John Fraser, of which he’s very fond – but Beethoven's for the D minor was magnificent on its own terms. And in any case the orchestral playing, especially in the finale, was meatier, more Beethoven-like than you'd expect from a chamber orchestra playing Mozart. With, of course, wonderful work from the woodwind – exceptionally so from first oboist, Mizuho Yoshii, who somehow managed to make us forget that there weren't clarinets, the real stars of the concertos featuring them, in the D minor work.

Never underestimate the difficulties and rewards of Haydn. Tønnesen told me the morning after how taken aback he'd been by the demands of Symphony No. 95, as quirky a work as any of its late counterparts – the subtle tempo changes, the pick-ups after dramatic pauses (which allowed the sound to resonate in the Aula acoustics: the orchestra's CEO, Per Erik Kise Larsen, thinks they're a little harder since the Munchs were remounted with boards behind them, but it's still a near-ideal venue for a chamber orchestra). At any rate, all the maneouvres were achieved with a decisiveness and a personality I learnt more about from Tønnesen in the NCO's new office space, part of a splendidly converted 19th century bank with Venetian affectations on the outside. The conversion, which houses many key arts organisations based in Oslo, has handsome rehearsal spaces, several rooms good enough to allow for chamber music and a ground-floor hall where the NCO can hold concerts more relaxed than in the teetotal Aula; there's a bar at the back.

Tønnesen (pictured above) is clearly a questing soul. His first ambition was to be an artist; married to an actor, Hilde Grythe, he composes incidental music for plays and has also enlisted dramatic help in trying to get the players to break down what he calls “the fourth wall” between them and the audience. Dramatic readings, most recently from Tolstoy’s harrowing novella The Kreutzer Sonata to inform Tonnesen’s string transcription of the Janáček quartet based on the story of jealousy and murder, enhance the experience (a new CD set of both Janáček quartets and selections from the Tolstoy, in both Norwegian and English, has just been released).

Tønnesen (pictured above) is clearly a questing soul. His first ambition was to be an artist; married to an actor, Hilde Grythe, he composes incidental music for plays and has also enlisted dramatic help in trying to get the players to break down what he calls “the fourth wall” between them and the audience. Dramatic readings, most recently from Tolstoy’s harrowing novella The Kreutzer Sonata to inform Tonnesen’s string transcription of the Janáček quartet based on the story of jealousy and murder, enhance the experience (a new CD set of both Janáček quartets and selections from the Tolstoy, in both Norwegian and English, has just been released).

It’s all about communication. As concert-master of the Oslo Philharmonic, Tønnesen found himself frustrated by the low level of understanding which results from “three rehearsals and a performance”. That led to a crisis, not long after he’d founded the NCO, in which he seriously thought about giving up as a musician, only to be saved by a Swedish film, The Brothers Mozart, which spelled out to him the essence of creativity. There have been some ground-breaking projects with the NCO, chiefly “The Gates of Hell”, for which the players studied yoga and drama to emulate Rodin’s figures in the first half of the evening, the audience encouraged to walk around and study them, and played Strauss’s Metamorphosen in the second – from memory. If you can memorise that, and Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht, you can memorise anything.

Score-less performance is catching on over here: the Aurora Orchestra and Nicholas Collon have done it several times, with the greatest success at the Proms. It's not a gimmick, like colourful dress, cool lighting or letting the audience bring in drinks to encourage the young. Being able to communicate the inner meaning of the music both to your fellow-players and the audience is liberating. I witnessed the vivacious leadership of each of the string sections in the Oslo concert; but there, the score still ruled. In London, you get a chance in the Prokofiev and the Grieg to see what the memorisation principle means in practice. Don’t miss it.

- The Norwegian Chamber Orchestra and Leif Ove Andsnes in concert at the Cadogan Hall on Friday 17 March

- Leeds Town Hall appearance on Saturday 18 March

- Mozart is the focus of Andsnes' second Rosendal Chamber Music Festival this summer

- More classical reviews on theartsdesk

Next page: the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra perform the Rigaudon from Grieg's Holberg Suite and Strauss's Metamorphosen without scores

Madonnas and Miracles: The Holy Home in Renaissance Italy, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Lovely, scholarly, multi-sensory insight into domestic Italy 500 years ago

A lovely, scholarly and gently revelatory exhibition, Madonnas and Miracles explores a neglected area of the perennially popular and much-studied Italian Renaissance – the place of piety in the Renaissance home. We are used to admiring the great 15th- and 16th-century gilded altarpieces and religious frescoes of Italian churches, palace chapels and convents, but this exhibition – one of the main outcomes of a generous four- year European funded research project – shows how the laity experienced religion in the context of their everyday domestic lives, as well as during extraordinary occurrences, such as the experience of divine miracles within the intimacy of their own four walls.

So we have a fascinating array of higher-end religious images (painting, drawing and sculpture) created to facilitate domestic devotion (some by notable artists), alongside household objects such as cutlery, furniture, textiles, ceramics, votive panels, books, rosaries and jewellery, and even tiny, screwed-up pieces of paper containing images and prayers. Pedlars and merchants (taking advantage of early methods of mass production, such as printing) produced and sold a wide range of affordable products alongside the more elite works. These may be cheaper and simpler, such as an endearingly clumsy early painted statuette of the nursing Virgin – but they were nonetheless as deeply treasured as some of the more luxurious objects (for example, an exquisite carved ivory Comb with the Annunciation, c.1450–1500, pictured below, Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin). The show – which has deep tentacles into the University of Cambridge – looks at how richly religious imagery and home life interacted with each other, framing activities from getting up, eating, going about one’s business, avoiding everyday perils (e.g. rabid dogs) and going to bed, to landmark occasions such as marriage, birth and death (a home birth or a "good" death was, of course, an intensely spiritual experience). It also shows how ideals of domesticity helped shape ideas of spirituality, resulting in "homely" religious images that adults and children could readily identify with. The Master of the Osservanza’s small luminous painted triptych of the Birth of the Virgin, a suitable object for female devotion, shows us Mary’s aged mother Anna, propped up in a bed with a glorious golden counterpane (in a prosperous domestic interior) shortly after miraculously giving birth.

The show – which has deep tentacles into the University of Cambridge – looks at how richly religious imagery and home life interacted with each other, framing activities from getting up, eating, going about one’s business, avoiding everyday perils (e.g. rabid dogs) and going to bed, to landmark occasions such as marriage, birth and death (a home birth or a "good" death was, of course, an intensely spiritual experience). It also shows how ideals of domesticity helped shape ideas of spirituality, resulting in "homely" religious images that adults and children could readily identify with. The Master of the Osservanza’s small luminous painted triptych of the Birth of the Virgin, a suitable object for female devotion, shows us Mary’s aged mother Anna, propped up in a bed with a glorious golden counterpane (in a prosperous domestic interior) shortly after miraculously giving birth.

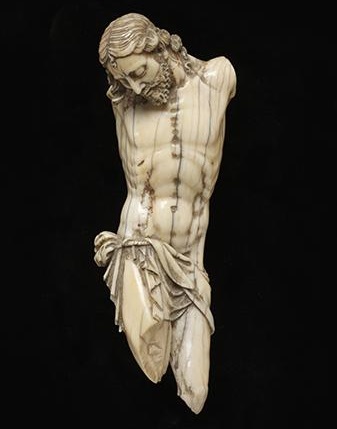

The Fitzwilliam’s galleries have been broken up into small, richly coloured (forest green), Renaissance rooms with low-level lighting, so that the colours and materials of the paintings and objects really glow – to encourage prolonged looking. It works beautifully. Giovanni Antonio Gualterio’s ivory of Christ’s Corpus for a Crucifix , c.1599 (pictured)– which would be easily overlooked in its London "home" (amongst the treasures of the V&A in London) – is one of the highlights of the show. It succeeds (as it would as a treasured object in a private context) in inviting identification with Christ’s humanity and suffering and is intended, no doubt, to inspire love mingled with pain and acceptance.

The Fitzwilliam’s galleries have been broken up into small, richly coloured (forest green), Renaissance rooms with low-level lighting, so that the colours and materials of the paintings and objects really glow – to encourage prolonged looking. It works beautifully. Giovanni Antonio Gualterio’s ivory of Christ’s Corpus for a Crucifix , c.1599 (pictured)– which would be easily overlooked in its London "home" (amongst the treasures of the V&A in London) – is one of the highlights of the show. It succeeds (as it would as a treasured object in a private context) in inviting identification with Christ’s humanity and suffering and is intended, no doubt, to inspire love mingled with pain and acceptance.

Another highlight of the show is a large domestic "tondo" (round) panel painting from the studio of Botticelli, fresh from its recent conservation, with the dull varnish removed and the original vibrancy revealed. It is a refined, decorative and tender work, rendered affordable (for home consumption) by the fact that it is a studio production, lacking the emotional and compositional complexity of a work by Botticelli’s own hand, and devoid of the elaborate gold embellishment that a wealthy patron would have demanded.

A more archaic Madonna and Child by Pietro de Niccolo da Orvieto (first half of 15th century) – with its painted marble back – also revealed by recent cleaning shows how such an image (part Byzantine icon/part Renaissance naturalism/part dream-like abstraction) would have been handled as an object, with the Virgin’s intense and benign gaze designed to meet the reverent gaze of the viewer, while the Christ child’s hand delicately touching his mother’s neck invites touching back. (Pictured above left: Studio of Sandro Botticelli, Virgin and Child, c.1480–90 © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge)

A more archaic Madonna and Child by Pietro de Niccolo da Orvieto (first half of 15th century) – with its painted marble back – also revealed by recent cleaning shows how such an image (part Byzantine icon/part Renaissance naturalism/part dream-like abstraction) would have been handled as an object, with the Virgin’s intense and benign gaze designed to meet the reverent gaze of the viewer, while the Christ child’s hand delicately touching his mother’s neck invites touching back. (Pictured above left: Studio of Sandro Botticelli, Virgin and Child, c.1480–90 © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge)

A rare drawing by Fra Angelico of The Dead Christ (c.1432-4) has areas which are marked and abraded, possibly through the act of kissing and touching (the points of contact, as the catalogue explains, "seem to correspond with the places where Mary Magdalene and John the Evangelist touch and kiss Christ’s body in the Descent from the Cross altarpiece" (the figure is repeated from Fra Angelico’s masterpiece in the Museo di San Marco in Florence).

Among the more surprising objects are four 16th-century ebony or ivory-handled knives, each engraved with one of four voice parts and their associated music notation (see gallery of images overleaf). The effect, as the four voices sung the Benediction and Grace at the meal in a high-end home, can be experienced on the adjacent sound station (this is a well-designed multi-sensory exhibition). Another object, the humblest in the exhibition, is a tiny piece of paper, which would have probably been purchased cheaply in the piazza, containing three prayers (two on one side to protect against fever and thunderstorms, one on the other to protect against lost items). This early form of insurance – inhabiting a grey area between devotion, magic and superstition – would have been worn in a pouch close to the body.

At the end of the exhibition, we have the treat of being able to see 27 votive tablets, temporarily removed from the cluttered walls of three different church shrines in Italy, which have never been loaned before and are from three lesser-known regions (Naples, the Marche and the Venetian terrafirma). These cheap-as-chips panels, painted in tempera, give thanks for miracles received, with their imagery reflecting the response to prayers in moments of crisis (when the Virgin or Saints intervene on a family’s behalf). One – from the same area that has recently been ravaged by earthquakes – poignantly shows buildings collapsing from earthquake tremors around a family praying fervently in a domestic interior (who survived to commission the plaque). Here, thanks to this jewel of a show, we truly have history and a history of art told by ordinary people, rather than by wealthy rulers and learned institutions.

- Madonnas and Miracles: The Holy Home in Renaissance Italy at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge until 4 June

- More visual art reviews on theartsdesk

Bruegel, Holburne Museum, Bath

A distinguished artistic lineage explored through one of the country's finest collections

Painted in c.1640, David Teniers the Younger’s Boy Blowing Bubbles depicts a theme that would have been entirely familiar to his wife’s great-grandfather, the founder of one of art’s most illustrious dynasties, Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c.1525-1569). Indicating the fleeting nature of life, the motif carries proverbial associations, its moral message one that in the 17th century was understood principally as memento mori.

Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun, National Portrait Gallery

Gender and identity explored by artists born 70 years apart

This show of work by two artists who use photography to explore the complexities of their own identity has to be the most interesting exhibition ever staged at the National Portrait Gallery, and opening in the same week as International Women's Day couldn't be more fitting.