A lovely, scholarly and gently revelatory exhibition, Madonnas and Miracles explores a neglected area of the perennially popular and much-studied Italian Renaissance – the place of piety in the Renaissance home. We are used to admiring the great 15th- and 16th-century gilded altarpieces and religious frescoes of Italian churches, palace chapels and convents, but this exhibition – one of the main outcomes of a generous four- year European funded research project – shows how the laity experienced religion in the context of their everyday domestic lives, as well as during extraordinary occurrences, such as the experience of divine miracles within the intimacy of their own four walls.

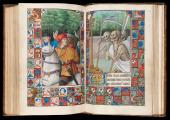

So we have a fascinating array of higher-end religious images (painting, drawing and sculpture) created to facilitate domestic devotion (some by notable artists), alongside household objects such as cutlery, furniture, textiles, ceramics, votive panels, books, rosaries and jewellery, and even tiny, screwed-up pieces of paper containing images and prayers. Pedlars and merchants (taking advantage of early methods of mass production, such as printing) produced and sold a wide range of affordable products alongside the more elite works. These may be cheaper and simpler, such as an endearingly clumsy early painted statuette of the nursing Virgin – but they were nonetheless as deeply treasured as some of the more luxurious objects (for example, an exquisite carved ivory Comb with the Annunciation, c.1450–1500, pictured below, Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin). The show – which has deep tentacles into the University of Cambridge – looks at how richly religious imagery and home life interacted with each other, framing activities from getting up, eating, going about one’s business, avoiding everyday perils (e.g. rabid dogs) and going to bed, to landmark occasions such as marriage, birth and death (a home birth or a "good" death was, of course, an intensely spiritual experience). It also shows how ideals of domesticity helped shape ideas of spirituality, resulting in "homely" religious images that adults and children could readily identify with. The Master of the Osservanza’s small luminous painted triptych of the Birth of the Virgin, a suitable object for female devotion, shows us Mary’s aged mother Anna, propped up in a bed with a glorious golden counterpane (in a prosperous domestic interior) shortly after miraculously giving birth.

The show – which has deep tentacles into the University of Cambridge – looks at how richly religious imagery and home life interacted with each other, framing activities from getting up, eating, going about one’s business, avoiding everyday perils (e.g. rabid dogs) and going to bed, to landmark occasions such as marriage, birth and death (a home birth or a "good" death was, of course, an intensely spiritual experience). It also shows how ideals of domesticity helped shape ideas of spirituality, resulting in "homely" religious images that adults and children could readily identify with. The Master of the Osservanza’s small luminous painted triptych of the Birth of the Virgin, a suitable object for female devotion, shows us Mary’s aged mother Anna, propped up in a bed with a glorious golden counterpane (in a prosperous domestic interior) shortly after miraculously giving birth.

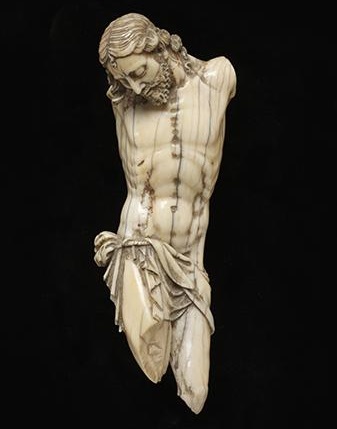

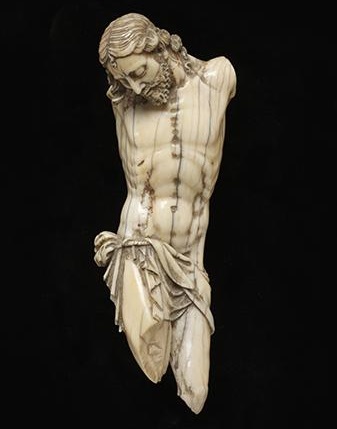

The Fitzwilliam’s galleries have been broken up into small, richly coloured (forest green), Renaissance rooms with low-level lighting, so that the colours and materials of the paintings and objects really glow – to encourage prolonged looking. It works beautifully. Giovanni Antonio Gualterio’s ivory of Christ’s Corpus for a Crucifix , c.1599 (pictured)– which would be easily overlooked in its London "home" (amongst the treasures of the V&A in London) – is one of the highlights of the show. It succeeds (as it would as a treasured object in a private context) in inviting identification with Christ’s humanity and suffering and is intended, no doubt, to inspire love mingled with pain and acceptance.

The Fitzwilliam’s galleries have been broken up into small, richly coloured (forest green), Renaissance rooms with low-level lighting, so that the colours and materials of the paintings and objects really glow – to encourage prolonged looking. It works beautifully. Giovanni Antonio Gualterio’s ivory of Christ’s Corpus for a Crucifix , c.1599 (pictured)– which would be easily overlooked in its London "home" (amongst the treasures of the V&A in London) – is one of the highlights of the show. It succeeds (as it would as a treasured object in a private context) in inviting identification with Christ’s humanity and suffering and is intended, no doubt, to inspire love mingled with pain and acceptance.

Another highlight of the show is a large domestic "tondo" (round) panel painting from the studio of Botticelli, fresh from its recent conservation, with the dull varnish removed and the original vibrancy revealed. It is a refined, decorative and tender work, rendered affordable (for home consumption) by the fact that it is a studio production, lacking the emotional and compositional complexity of a work by Botticelli’s own hand, and devoid of the elaborate gold embellishment that a wealthy patron would have demanded.

A more archaic Madonna and Child by Pietro de Niccolo da Orvieto (first half of 15th century) – with its painted marble back – also revealed by recent cleaning shows how such an image (part Byzantine icon/part Renaissance naturalism/part dream-like abstraction) would have been handled as an object, with the Virgin’s intense and benign gaze designed to meet the reverent gaze of the viewer, while the Christ child’s hand delicately touching his mother’s neck invites touching back. (Pictured above left: Studio of Sandro Botticelli, Virgin and Child, c.1480–90 © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge)

A more archaic Madonna and Child by Pietro de Niccolo da Orvieto (first half of 15th century) – with its painted marble back – also revealed by recent cleaning shows how such an image (part Byzantine icon/part Renaissance naturalism/part dream-like abstraction) would have been handled as an object, with the Virgin’s intense and benign gaze designed to meet the reverent gaze of the viewer, while the Christ child’s hand delicately touching his mother’s neck invites touching back. (Pictured above left: Studio of Sandro Botticelli, Virgin and Child, c.1480–90 © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge)

A rare drawing by Fra Angelico of The Dead Christ (c.1432-4) has areas which are marked and abraded, possibly through the act of kissing and touching (the points of contact, as the catalogue explains, "seem to correspond with the places where Mary Magdalene and John the Evangelist touch and kiss Christ’s body in the Descent from the Cross altarpiece" (the figure is repeated from Fra Angelico’s masterpiece in the Museo di San Marco in Florence).

Among the more surprising objects are four 16th-century ebony or ivory-handled knives, each engraved with one of four voice parts and their associated music notation (see gallery of images overleaf). The effect, as the four voices sung the Benediction and Grace at the meal in a high-end home, can be experienced on the adjacent sound station (this is a well-designed multi-sensory exhibition). Another object, the humblest in the exhibition, is a tiny piece of paper, which would have probably been purchased cheaply in the piazza, containing three prayers (two on one side to protect against fever and thunderstorms, one on the other to protect against lost items). This early form of insurance – inhabiting a grey area between devotion, magic and superstition – would have been worn in a pouch close to the body.

At the end of the exhibition, we have the treat of being able to see 27 votive tablets, temporarily removed from the cluttered walls of three different church shrines in Italy, which have never been loaned before and are from three lesser-known regions (Naples, the Marche and the Venetian terrafirma). These cheap-as-chips panels, painted in tempera, give thanks for miracles received, with their imagery reflecting the response to prayers in moments of crisis (when the Virgin or Saints intervene on a family’s behalf). One – from the same area that has recently been ravaged by earthquakes – poignantly shows buildings collapsing from earthquake tremors around a family praying fervently in a domestic interior (who survived to commission the plaque). Here, thanks to this jewel of a show, we truly have history and a history of art told by ordinary people, rather than by wealthy rulers and learned institutions.

Click for more images from the exhibition

The show – which has deep tentacles into the University of Cambridge – looks at how richly religious imagery and home life interacted with each other, framing activities from getting up, eating, going about one’s business, avoiding everyday perils (e.g. rabid dogs) and going to bed, to landmark occasions such as marriage, birth and death (a home birth or a "good" death was, of course, an intensely spiritual experience). It also shows how ideals of domesticity helped shape ideas of spirituality, resulting in "homely" religious images that adults and children could readily identify with. The Master of the Osservanza’s small luminous painted triptych of the Birth of the Virgin, a suitable object for female devotion, shows us Mary’s aged mother Anna, propped up in a bed with a glorious golden counterpane (in a prosperous domestic interior) shortly after miraculously giving birth.

The show – which has deep tentacles into the University of Cambridge – looks at how richly religious imagery and home life interacted with each other, framing activities from getting up, eating, going about one’s business, avoiding everyday perils (e.g. rabid dogs) and going to bed, to landmark occasions such as marriage, birth and death (a home birth or a "good" death was, of course, an intensely spiritual experience). It also shows how ideals of domesticity helped shape ideas of spirituality, resulting in "homely" religious images that adults and children could readily identify with. The Master of the Osservanza’s small luminous painted triptych of the Birth of the Virgin, a suitable object for female devotion, shows us Mary’s aged mother Anna, propped up in a bed with a glorious golden counterpane (in a prosperous domestic interior) shortly after miraculously giving birth. The Fitzwilliam’s galleries have been broken up into small, richly coloured (forest green), Renaissance rooms with low-level lighting, so that the colours and materials of the paintings and objects really glow – to encourage prolonged looking. It works beautifully. Giovanni Antonio Gualterio’s ivory of Christ’s Corpus for a Crucifix , c.1599 (pictured)– which would be easily overlooked in its London "home" (amongst the treasures of the V&A in London) – is one of the highlights of the show. It succeeds (as it would as a treasured object in a private context) in inviting identification with Christ’s humanity and suffering and is intended, no doubt, to inspire love mingled with pain and acceptance.

The Fitzwilliam’s galleries have been broken up into small, richly coloured (forest green), Renaissance rooms with low-level lighting, so that the colours and materials of the paintings and objects really glow – to encourage prolonged looking. It works beautifully. Giovanni Antonio Gualterio’s ivory of Christ’s Corpus for a Crucifix , c.1599 (pictured)– which would be easily overlooked in its London "home" (amongst the treasures of the V&A in London) – is one of the highlights of the show. It succeeds (as it would as a treasured object in a private context) in inviting identification with Christ’s humanity and suffering and is intended, no doubt, to inspire love mingled with pain and acceptance. A more archaic Madonna and Child by Pietro de Niccolo da Orvieto (first half of 15th century) – with its painted marble back – also revealed by recent cleaning shows how such an image (part Byzantine icon/part Renaissance naturalism/part dream-like abstraction) would have been handled as an object, with the Virgin’s intense and benign gaze designed to meet the reverent gaze of the viewer, while the Christ child’s hand delicately touching his mother’s neck invites touching back. (Pictured above left: Studio of Sandro Botticelli, Virgin and Child, c.1480–90 © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge)

A more archaic Madonna and Child by Pietro de Niccolo da Orvieto (first half of 15th century) – with its painted marble back – also revealed by recent cleaning shows how such an image (part Byzantine icon/part Renaissance naturalism/part dream-like abstraction) would have been handled as an object, with the Virgin’s intense and benign gaze designed to meet the reverent gaze of the viewer, while the Christ child’s hand delicately touching his mother’s neck invites touching back. (Pictured above left: Studio of Sandro Botticelli, Virgin and Child, c.1480–90 © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge)