As its title foretells, Moonlight is a luminous film. It shines light on experiences that may be completely different from our own, drawing us in with utter empathy. Director Barry Jenkins shows his lead character finding his way out of darkness, through pain, to attain a tentative revelation of self-acceptance. Yet this is no direct or glaring light: Jenkins shows himself a master of nuance, working with a script that is light on words but speaks unforgettably in the primal language of cinema itself.

It’s an independent film in the essence of that term, something that makes its progression to the front ranks of this year’s Academy Awards all the more impressive. And how skilfully Moonlight confounds definition by the categories into which it might easily be slotted – as a gay film, or a black film, however much both elements are crucial to its identity.

What’s more important is that Chiron is somehow learning to trust

To achieve something so universal, Jenkins has set his drama in a very particular location, the Liberty City district of Miami. It was where the director himself grew up, as did Tarell Alvin McCraney, the writer from whose original drama treatment In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue the film is adapted. The two did not know each other then: what they did share in youth, however, was the experience of growing up with mothers who had drug addiction issues.

It’s there that we first encounter the film’s hero, 10-year-old Chiron (Alex Hibbert, slight, silent), who’s known as “Little”, the word that gives the first of Moonlight’s three sections its title. The second, which carries the boy’s given name, catches him at 16, now played by Ashton Sanders, gangly and avoiding eye contact. The third, with Chiron a young adult, is titled “Black”, after the moniker he’s now given himself (also an affectionately bestowed nickname he had acquired in the middle episode). It’s not only physical slightness that sets Chiron apart: he’s treated as an outsider by his more aggressive contemporaries for another reason, one which they sense but he himself has not yet registered. The film opens with the latest of what we guess is a series of rejections, but this one ends on a more positive note with Little befriended by Juan (Mahershala Ali). Of Cuban descent, Juan may be a community hard man and drug dealer, but he shows only kindness to this resolutely silent youngster, first feeding him and then taking him home to his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe).

It’s not only physical slightness that sets Chiron apart: he’s treated as an outsider by his more aggressive contemporaries for another reason, one which they sense but he himself has not yet registered. The film opens with the latest of what we guess is a series of rejections, but this one ends on a more positive note with Little befriended by Juan (Mahershala Ali). Of Cuban descent, Juan may be a community hard man and drug dealer, but he shows only kindness to this resolutely silent youngster, first feeding him and then taking him home to his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe).

Her home becomes a place of refuge for the troubled Chiron as the circumstances of his home life with mother Paula (Naomie Harris, falling gradually and hauntingly into full crack addiction), as well as that of this “adopted” family change. The other anchor point of Chiron’s world is his friendship with his contemporary Kevin, shown from innocent childhood games through to more loaded adolescent encounters, a bond that will also presage damage as the film progresses.

“At some point you've got to decide who you wanna be. Can’t let nobody make that decision for you,” Juan tells the boy at one point, his phrase catching the essence of what Moonlight is about: the shaping, the realisation of the eventual adult character. Juan’s words come shortly after one of the film’s tenderest moments, as he teaches the child to swim, though what’s actually more important is that Chiron is somehow learning to trust. The tragic irony that Ali’s character, the one who shows such concern for Chiron, is also dealing the substances that are bringing his mother down, prompts one of the most poignant moments of the first episode.

The defining moment of the succeeding section also takes place at the sea, as Chiron and Kevin talk on the beach (pictured above, Jharrel Jerome, left, with Ashton Sanders): Chiron once more risks trust, relaxing the barriers of self-protection that he has constructed around himself (“I cry so much sometimes I might turn to drops”, he poignantly reveals). The cruelty is that hurt will again follow revelation, culminating in an act of self-assertion that will change the course of the young man’s life, sending him away from his home environment.

The defining moment of the succeeding section also takes place at the sea, as Chiron and Kevin talk on the beach (pictured above, Jharrel Jerome, left, with Ashton Sanders): Chiron once more risks trust, relaxing the barriers of self-protection that he has constructed around himself (“I cry so much sometimes I might turn to drops”, he poignantly reveals). The cruelty is that hurt will again follow revelation, culminating in an act of self-assertion that will change the course of the young man’s life, sending him away from his home environment.

But distance is not the only change that comes with Moonlight’s final part. Trevante Rhodes (an erstwhile professional sportsman himself, physically powerful here, yet so damaged inside) plays the now adult Black, who’s bulked himself up protectively: he’s become a dealer, like his first mentor Juan, with a muscled body to match, teeth ribbed in gold. When Black makes an almost impromptu journey from his new home territory, Atlanta, back to Miami, his whole life comes up for reappraisal. (Pictured above: André Holland, left, with Trevante Rhodes.)

Jenkins’ choice of an elliptical narrative structure, one that registers change rather than spelling it out, is a stroke of genius. It also makes for the sheer freshness of impression that is so powerful in Moonlight, suitable not only for a story anchored in childhood, but also involving a hero who’s at times reticent almost to the point of speechlessness. It's as if the director defines his canvas through spots of colour that coalesce into an image, rather than through any direct stroke of the brush.

Moonlight’s visual sense is highly painterly, too, from the pastel tones of the Liberty City locations (James Laxton’s cinematography catches them with an easy beauty that surely belies their real character) through to the distinct colour orientations of the film’s three parts. There’s a sheer confidence in Nicholas Britell’s score too, melding what we might expect – rap, jukebox melodies – with the grand emotional assertions of Mozart. Comparisons already drawn with the likes of Terrence Malick are not incidental, such is Jenkins’s sheer flair: it's only his second feature, and to draw this quality of performance from his three male leads and supporting players alike is an almost impeccable achievement. Revelatory filmmaking.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Moonlight

That means he hardly knows his younger sister Suzanne (Léa Seydoux) at all, and is meeting sister-in-law Catherine (Marion Cotillard) for the first time, though she and her husband Antoine (Vincent Cassel) have named one of their children after him. These two female characters are the ones that come closest to him: Cotillard’s character is especially sensitive, as she instinctively understands the issue – even if her words “Combien de temps?” lose much of their acuity in translation – that does finally remain unspoken.

That means he hardly knows his younger sister Suzanne (Léa Seydoux) at all, and is meeting sister-in-law Catherine (Marion Cotillard) for the first time, though she and her husband Antoine (Vincent Cassel) have named one of their children after him. These two female characters are the ones that come closest to him: Cotillard’s character is especially sensitive, as she instinctively understands the issue – even if her words “Combien de temps?” lose much of their acuity in translation – that does finally remain unspoken. Nathalie Baye plays Martine, the matriarch. Though it’s the entire family that is on the edge of a nervous breakdown, we certainly sense where it came from. Dolan has a record of harping on mothers – his debut film was titled I Killed My Mother, his most recent one just Mommy – but actually that isn’t the dominating relationship here, rather it’s the whole entity that is under cruel scrutiny. (Nathalie Baye with Gaspard Ulliel, pictured above right.)

Nathalie Baye plays Martine, the matriarch. Though it’s the entire family that is on the edge of a nervous breakdown, we certainly sense where it came from. Dolan has a record of harping on mothers – his debut film was titled I Killed My Mother, his most recent one just Mommy – but actually that isn’t the dominating relationship here, rather it’s the whole entity that is under cruel scrutiny. (Nathalie Baye with Gaspard Ulliel, pictured above right.)

It’s not only physical slightness that sets Chiron apart: he’s treated as an outsider by his more aggressive contemporaries for another reason, one which they sense but he himself has not yet registered. The film opens with the latest of what we guess is a series of rejections, but this one ends on a more positive note with Little befriended by Juan (Mahershala Ali). Of Cuban descent, Juan may be a community hard man and drug dealer, but he shows only kindness to this resolutely silent youngster, first feeding him and then taking him home to his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe).

It’s not only physical slightness that sets Chiron apart: he’s treated as an outsider by his more aggressive contemporaries for another reason, one which they sense but he himself has not yet registered. The film opens with the latest of what we guess is a series of rejections, but this one ends on a more positive note with Little befriended by Juan (Mahershala Ali). Of Cuban descent, Juan may be a community hard man and drug dealer, but he shows only kindness to this resolutely silent youngster, first feeding him and then taking him home to his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe). The defining moment of the succeeding section also takes place at the sea, as Chiron and Kevin talk on the beach (pictured above, Jharrel Jerome, left, with Ashton Sanders): Chiron once more risks trust, relaxing the barriers of self-protection that he has constructed around himself (“I cry so much sometimes I might turn to drops”, he poignantly reveals). The cruelty is that hurt will again follow revelation, culminating in an act of self-assertion that will change the course of the young man’s life, sending him away from his home environment.

The defining moment of the succeeding section also takes place at the sea, as Chiron and Kevin talk on the beach (pictured above, Jharrel Jerome, left, with Ashton Sanders): Chiron once more risks trust, relaxing the barriers of self-protection that he has constructed around himself (“I cry so much sometimes I might turn to drops”, he poignantly reveals). The cruelty is that hurt will again follow revelation, culminating in an act of self-assertion that will change the course of the young man’s life, sending him away from his home environment.

As we make the journey through Hockney’s oeuvre – one that the artist has also clearly enjoyed revisiting – we move from his formative pictures as a student at the Royal College of Art in London, through to the breakthrough

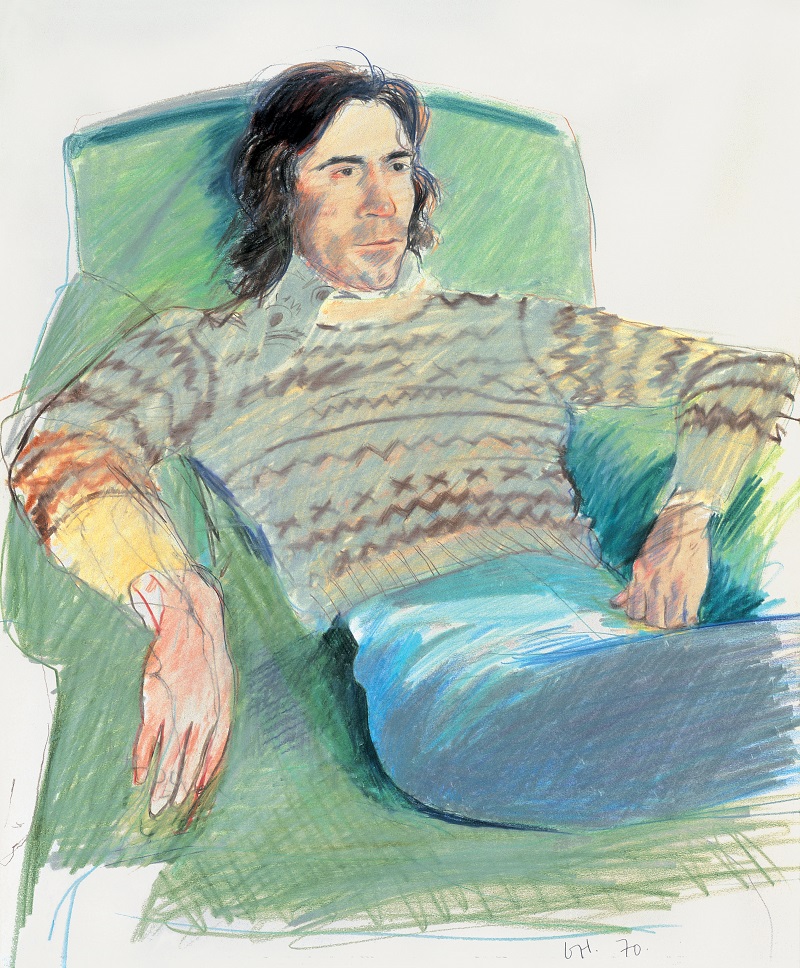

As we make the journey through Hockney’s oeuvre – one that the artist has also clearly enjoyed revisiting – we move from his formative pictures as a student at the Royal College of Art in London, through to the breakthrough  Hockney sees himself as a humanist: his reaction to the dominance of abstract art was to paint "pictures with people in": and not just any people. His sitters are usually friends, family or lovers. He came out early – while at college – deciding to embrace his homosexuality in his art; these paintings reflect his life and boyish humour, from escapades with early boyfriends to graffiti in the gent’s toilets. By being so constantly self-referential, Hockney became drawn to ambiguity, both in terms of the way we see the world, and the way the world sees us. (Pictured above right: Ossie Wearing a Fairisle Sweater, 1970. Private collection, London © David Hockney)

Hockney sees himself as a humanist: his reaction to the dominance of abstract art was to paint "pictures with people in": and not just any people. His sitters are usually friends, family or lovers. He came out early – while at college – deciding to embrace his homosexuality in his art; these paintings reflect his life and boyish humour, from escapades with early boyfriends to graffiti in the gent’s toilets. By being so constantly self-referential, Hockney became drawn to ambiguity, both in terms of the way we see the world, and the way the world sees us. (Pictured above right: Ossie Wearing a Fairisle Sweater, 1970. Private collection, London © David Hockney) Hockney’s interest in the human is intimately entwined with a feeling for the character of a place. The exhibition includes the winding hilly landscapes of his home in the Hollywood Hills (their fauvist colours capturing the dizzying journey to his Santa Monica studio) and the glowing landscapes of the Grand Canyon, followed by a contrasting room of Hockney’s expansive Yorkshire landscapes – selected from the many canvases that Hockney produced for his 2012 blockbuster at the

Hockney’s interest in the human is intimately entwined with a feeling for the character of a place. The exhibition includes the winding hilly landscapes of his home in the Hollywood Hills (their fauvist colours capturing the dizzying journey to his Santa Monica studio) and the glowing landscapes of the Grand Canyon, followed by a contrasting room of Hockney’s expansive Yorkshire landscapes – selected from the many canvases that Hockney produced for his 2012 blockbuster at the

Just how serious becomes apparent as Jason’s fate unfolds. This premier football world is one in which being gay and becoming a star are anathema: we remember all too well the only first-class player who revealed his homosexuality, or very possibly, was forced to do so by the threat of tabloid exposure –

Just how serious becomes apparent as Jason’s fate unfolds. This premier football world is one in which being gay and becoming a star are anathema: we remember all too well the only first-class player who revealed his homosexuality, or very possibly, was forced to do so by the threat of tabloid exposure –  Arinze Kene as Ade is the only one not from the original

Arinze Kene as Ade is the only one not from the original

They may have a shared purpose for that moment – the film’s French title, Theo & Hugo dans le meme bateau, brings home how they are temporarily indeed “in the same boat” – but it’s the rather freer element of their nocturnal wanderings that really impresses (as does Manuel Marmier’s fluid, atmospheric cinematography). “Paris belongs to us” could almost be a subtitle for the film, as the streets of its northeastern quarters provide a loose backdrop for the couple’s deepening acquaintance; observation of some of the characters they encounter is sensitive, too. Couet and Nambot establish their characters with nicely contrasting touches: the Parisian Theo is reserved, Hugo, an escapee from the provinces, much more impulsive, the latter especially drawing out the writing's humour.

They may have a shared purpose for that moment – the film’s French title, Theo & Hugo dans le meme bateau, brings home how they are temporarily indeed “in the same boat” – but it’s the rather freer element of their nocturnal wanderings that really impresses (as does Manuel Marmier’s fluid, atmospheric cinematography). “Paris belongs to us” could almost be a subtitle for the film, as the streets of its northeastern quarters provide a loose backdrop for the couple’s deepening acquaintance; observation of some of the characters they encounter is sensitive, too. Couet and Nambot establish their characters with nicely contrasting touches: the Parisian Theo is reserved, Hugo, an escapee from the provinces, much more impulsive, the latter especially drawing out the writing's humour.