What a pity Beethoven never composed an appendage to Fidelio called The Sorrows of Young Marzelline. One crucial moment apart, the music he gives to his second soprano in his only opera isn't his best, but Louise Alder so lived the role of the gaoler's daughter in love with a woman disguised as a man that everything else felt rather less intense. It's only fair to say that there were other singers facing bigger challenges very stylishly, for the most part, but neither they nor the BBC Philharmonic under its chief conductor Juanjo Menja made us feel as though their lives depended on the outcome. And that ultimate lack of blazing commitment, in what should be the most incandescent of prison dramas, sold it all a bit short.

True, this was an unashamed concert-performance Prom with no directorial supervision, principals delivering score-free – with one exception, James Creswell, a more than adequate late replacement for Brindley Sherratt as gaoler Rocco – in front of the orchestra, with co-ordination not always the tightest. This, Beethoven's much more celebrated revision of the original Leonore swapping drama for a pageant-finale, worked best in that oratorio-like final scene – though like much else it was bright and pleasant rather than shattering or deeply moving. It was hard to come from the Chamber Orchestra of Europe under Haitink, projecting every phrase of Mozart and Schumann into the Albert Hall space, and be brought back down to earth with the more usual situation of fuzzy strings lacking ideal bite. No doubt the answer would be to stand in the Arena, an occasional option, but no way was this playing on the same level. And the horns were having a bad night.

Nor was focus always there in Ricarda Merbeth's Leonore (pictured above with Stuart Skelton – nice dress, but a trouser suit would have been more appropriate for the heroine's male disguise). Her lower middle-range tended to disappear in these acoustics, though it was obvious why she's a fit for the part: no soprano I've heard live has essayed the testing top so fully or flawlessly. None, either, has made clearer work of what can be a treacherous bark of a duet when the wife who's risked her life for her political-prisoner husband is finally reunited with him. Stuart Skelton could manage it, too, though even he was tested by the ludicrous high vision of "an angel, Leonore" at the end of his aria: perhaps it can only work as part of a stage performance delivered in extremis. Skelton was otherwise palpably in control, phrasing stylishly and weighting the big entry on the word "Gott", swelling it as only a heroic tenor can.

Nor was focus always there in Ricarda Merbeth's Leonore (pictured above with Stuart Skelton – nice dress, but a trouser suit would have been more appropriate for the heroine's male disguise). Her lower middle-range tended to disappear in these acoustics, though it was obvious why she's a fit for the part: no soprano I've heard live has essayed the testing top so fully or flawlessly. None, either, has made clearer work of what can be a treacherous bark of a duet when the wife who's risked her life for her political-prisoner husband is finally reunited with him. Stuart Skelton could manage it, too, though even he was tested by the ludicrous high vision of "an angel, Leonore" at the end of his aria: perhaps it can only work as part of a stage performance delivered in extremis. Skelton was otherwise palpably in control, phrasing stylishly and weighting the big entry on the word "Gott", swelling it as only a heroic tenor can.

Villainous prison governor Pizarro can only work at a level of testosterone-driven edginess; Detlef Roth conveyed nothing more than a petulant bank-manager, despite a couple of energetic footstamps. Creswell's subordinate could have eaten him for breakfast; as they sang alongside each other, one got the feeling of the same mésalliance as when King Philip in Verdi's Don Carlos has more vocal power than the only one supposedly lording it over him, the Grand Inquisitor. We could have done with more colours and force from the Orfeón Donostiarra, Spain's finest choral society, playing their compatriots albeit singing in German, but emphatically not the essential professional opera chorus. Better, perhaps, to have assembled voices from the London music colleges.

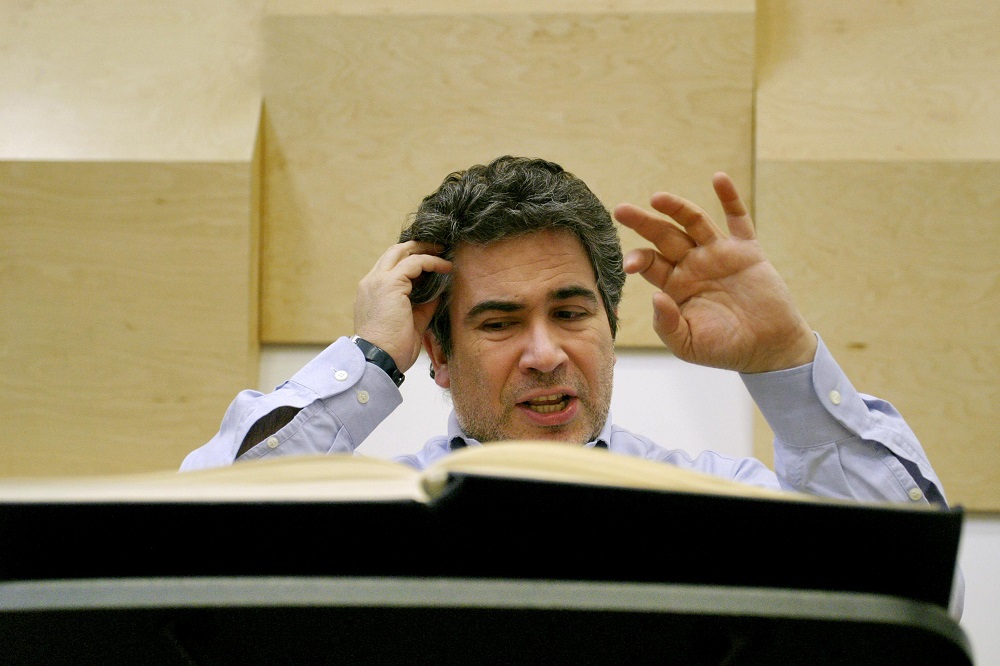

Only the three not-so-long graduated young Brits in the cast offered perfection. Alder (pictured above with Mena), having made her surprise Proms debut three years ago stepping in as the Glyndebourne cover Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier, has deservedly shot to fame since then, winning the Dame Joan Sutherland Audience Prize at the BBC 2017 Cardiff Singer of the World Competition, and she owns the stage. Her launch of the great canon-quartet "Mir ist so wunderbar" provided the one truly moving moment of the evening. Tenor Benjamin Hulett was a fine match as the lad her Marzelline treats so badly, and David Soar declaimed to perfection as deus ex machina Don Fernando. But inevitably their subordinate roles were limited.

Only the three not-so-long graduated young Brits in the cast offered perfection. Alder (pictured above with Mena), having made her surprise Proms debut three years ago stepping in as the Glyndebourne cover Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier, has deservedly shot to fame since then, winning the Dame Joan Sutherland Audience Prize at the BBC 2017 Cardiff Singer of the World Competition, and she owns the stage. Her launch of the great canon-quartet "Mir ist so wunderbar" provided the one truly moving moment of the evening. Tenor Benjamin Hulett was a fine match as the lad her Marzelline treats so badly, and David Soar declaimed to perfection as deus ex machina Don Fernando. But inevitably their subordinate roles were limited.

Amplifying the (minimal) spoken dialogue meant a plunge in levels for the music. Cultivated, mostly lively orchestral playing just needed more heft, despite excellent work from timpanist Paul Turner. It didn't tell the story by itself, and given that the Proms organisers still won't provide supertitle screens around the hall – it can be done – more of the performers needed to work harder to carry the narrative and compel focus from those in the audience with their heads in the programme.

Next page: watch Louise Alder sing 'No word from Tom' from Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress at the BBC Cardiff Singer of the World Competition

Nor was focus always there in Ricarda Merbeth's Leonore (pictured above with Stuart Skelton – nice dress, but a trouser suit would have been more appropriate for the heroine's male disguise). Her lower middle-range tended to disappear in these acoustics, though it was obvious why she's a fit for the part: no soprano I've heard live has essayed the testing top so fully or flawlessly. None, either, has made clearer work of what can be a treacherous bark of a duet when the wife who's risked her life for her political-prisoner husband is finally reunited with him. Stuart Skelton could manage it, too, though even he was tested by the ludicrous high vision of "an angel, Leonore" at the end of his aria: perhaps it can only work as part of a stage performance delivered in extremis. Skelton was otherwise palpably in control, phrasing stylishly and weighting the big entry on the word "Gott", swelling it as only a heroic tenor can.

Nor was focus always there in Ricarda Merbeth's Leonore (pictured above with Stuart Skelton – nice dress, but a trouser suit would have been more appropriate for the heroine's male disguise). Her lower middle-range tended to disappear in these acoustics, though it was obvious why she's a fit for the part: no soprano I've heard live has essayed the testing top so fully or flawlessly. None, either, has made clearer work of what can be a treacherous bark of a duet when the wife who's risked her life for her political-prisoner husband is finally reunited with him. Stuart Skelton could manage it, too, though even he was tested by the ludicrous high vision of "an angel, Leonore" at the end of his aria: perhaps it can only work as part of a stage performance delivered in extremis. Skelton was otherwise palpably in control, phrasing stylishly and weighting the big entry on the word "Gott", swelling it as only a heroic tenor can. Only the three not-so-long graduated young Brits in the cast offered perfection. Alder (pictured above with Mena), having made her surprise Proms debut three years ago stepping in as the Glyndebourne cover Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier, has deservedly shot to fame since then, winning the Dame Joan Sutherland Audience Prize at the BBC 2017 Cardiff Singer of the World Competition, and she owns the stage. Her launch of the great canon-quartet "Mir ist so wunderbar" provided the one truly moving moment of the evening. Tenor Benjamin Hulett was a fine match as the lad her Marzelline treats so badly, and David Soar declaimed to perfection as deus ex machina Don Fernando. But inevitably their subordinate roles were limited.

Only the three not-so-long graduated young Brits in the cast offered perfection. Alder (pictured above with Mena), having made her surprise Proms debut three years ago stepping in as the Glyndebourne cover Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier, has deservedly shot to fame since then, winning the Dame Joan Sutherland Audience Prize at the BBC 2017 Cardiff Singer of the World Competition, and she owns the stage. Her launch of the great canon-quartet "Mir ist so wunderbar" provided the one truly moving moment of the evening. Tenor Benjamin Hulett was a fine match as the lad her Marzelline treats so badly, and David Soar declaimed to perfection as deus ex machina Don Fernando. But inevitably their subordinate roles were limited. But what of the unfamiliar, its presence linked by repertoire for two apparently great singers of the 19th century, Julie Doras-Grace and Gilbert Duprez? The best cases were made for an aria and duet from

But what of the unfamiliar, its presence linked by repertoire for two apparently great singers of the 19th century, Julie Doras-Grace and Gilbert Duprez? The best cases were made for an aria and duet from  We see the controversies around the Academy salons that sometimes ended in fights, though appreciating some century and a half later quite what such differences meant is sometimes challenging. More beguiling are visual recreations of some of the great works of Impressionism, notably Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, even if it can feel like an art-historical roll-call: you hear someone hailed as “Berthe”, you know it must be Morrisot. The travails of Cézanne’s creation, including his propensity to destroy his canvases, is there too, in as much as any film can convincingly convey the process of painting. There’s a painful moment when Cézanne, funded in his Paris atelier by Zola, learns that one of his works has actually sold – but only its central detail, an apple, cut out of the canvas on the whim of a client.

We see the controversies around the Academy salons that sometimes ended in fights, though appreciating some century and a half later quite what such differences meant is sometimes challenging. More beguiling are visual recreations of some of the great works of Impressionism, notably Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, even if it can feel like an art-historical roll-call: you hear someone hailed as “Berthe”, you know it must be Morrisot. The travails of Cézanne’s creation, including his propensity to destroy his canvases, is there too, in as much as any film can convincingly convey the process of painting. There’s a painful moment when Cézanne, funded in his Paris atelier by Zola, learns that one of his works has actually sold – but only its central detail, an apple, cut out of the canvas on the whim of a client.