10 Questions for Artist David Shrigley

The provocative artist talks festivals, moshpits, Google and much more

David Shrigley (b. 1968) is an artist whose work has become broadly popular via a wide range of formats. At first glance, his stark pen-on-paper drawings seem akin to humorous newspaper cartoons – and, indeed, he’s contributed to The Guardian for years – but there's another layer to his work, something odder, slyer, psychologically attuned to the relationship between the subconscious and the ruthlessness of the human condition.

As well as a long series of books and multiple exhibitions all around the world, including forthcoming ones this year in Shanghai, Stockholm and on the Greek island of Hydra, Shrigley has a strong track record of working with musicians. He has directed videos (Blur, Bonnie “Prince” Billy), designed cover art (Deerhoof, Malcolm Middleton, etc) and taken part in music (Worried Noodles, Music and Words, etc). He also created a strikingly bizarre mascot for Partick Thistle football club in 2015 and had his “thumbs up” sculpture Really Good on Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth until earlier this year.

Based in Glasgow for almost three decades, Shrigley moved to Brighton three years ago and is this year’s Guest Director of the Brighton Festival. His new book Fully Coherent Plan is published on 3 May 2018.

THOMAS H GREEN: What is your relationship with Brighton?

DAVID SHRIGLEY: I moved here in 2015. The festival’s been a really great thing to become embedded in the arts scene, a really nice social thing in practical terms of being an artist. My studio’s based here so I stay put in the mornings, unlike a lot of unfortunate people who have to go to London. I’ve enjoyed the Festival ever since coming here. It’s nice to have an obligation to see almost everything. Some years you end up wishing you’d been to things but never quite getting round to it, or they sold out.

DAVID SHRIGLEY: I moved here in 2015. The festival’s been a really great thing to become embedded in the arts scene, a really nice social thing in practical terms of being an artist. My studio’s based here so I stay put in the mornings, unlike a lot of unfortunate people who have to go to London. I’ve enjoyed the Festival ever since coming here. It’s nice to have an obligation to see almost everything. Some years you end up wishing you’d been to things but never quite getting round to it, or they sold out.

How has your involvement been?

I think if I hadn’t chosen to make the performance I’m making [“alt-rock/pop pantomime" Problem In Brighton] it’d probably be pretty easy but actually making a new piece where I’m out of my depth, having a hand in directing music, that’s quite exciting, something I really wanted to do. If I didn’t do it now I wouldn’t get round to it. Everything’s a bit fraught. We start rehearsing in a week [this interview took place in mid-April] so the actors are living in my basement, in my studio.

Why are they in there?

Because otherwise we’d have to pay for them to stay in a hotel. We’re trying to spend the budget wisely so everyone gets paid.

It’s a musical with a mosh-pit, right?

Yes, I suppose it’s really up to the audience whether a mosh-pit is involved.

Presumably some of the music is designed to that purpose?

It’s a bit moshy, yeah, so the fact it’s a standing gig lends itself to a bit of movement. We’ll see. We’ve got that in mind.

Which events at the festival have you particular emotional investment in?

I guess, like most people, I’ve read the brochure and press release. You have to see a few things before you find that one thing that’s an absolute gem, but you never really know what that’s going to be until you’ve seen everything. Last year we went to see ten things, probably none of which we had any prior knowledge of. Swan Lake at the Dome was the thing I really enjoyed last year [Irish dance/theatre company Teac Damsa’s Swan Lake/Loch na hEala]. I really wouldn’t have anticipated liking that. You’d think a modern interpretation of Swan Lake set in urban Dublin, gritty realism meets a ballet… no. But it was fantastic. You have to make the effort.

How did you persuade singer-songwriter Malcolm Middleton to perform at the festival? I thought he’d given up doing shows with his acoustic guitar...

[Laughing wryly] I guess he feels he owes me. We’ve become good friends over the years and he knows I’m a big fan of what he does. I think he’s making a special exception for me. In general, with his music he’s restless creatively, always wanting to do something different. There’s the [experimental] Human Don’t Be Angry stuff, the collaboration we did [Music and Words], then there’s Arab Strap as well with Aidan Moffat. He just doesn’t want to have to do the same thing again and again in order to make money, because you’ve got to still love it. If you don’t, it makes it difficult to do it. I understand the predicament he’s in, but I do love his acoustic stuff. I love that performance, just him and his guitar.

Which of your works are you most often asked about by journalists and humans in general?

There’s a lot of really juicy music at the Brighton Festival this year, but if you could curate an epic Glastonbury-style green field affair, with money no object, who would be on?

I wouldn’t go to a green field festival. I hate festivals. I’m a bit of a germophobe. I don’t like chemical toilets and I need to wash my hands under running water. I’m a bit of an armchair traveller. I spent my entire childhood on camping holidays and by the time I’d got to 16 I was completely done with holidaying under canvas. That’s another thing I don’t like, the trek to the toilet block in the middle of the night. I gave Brighton Festival a list of things I wanted. I really didn’t expect them to get it all together. Deerhoof is quite a disparate group and Ezra Furman is from the States as well. There was a plan to get Mogwai to play at the Dome but they were busy. Certain acts work at festivals but perhaps don’t work so well at one-off gigs. I always think Sleaford Mods are a really good festival band because somehow their presentation of sound seems to work wherever they play because it’s so sparse and abrasive. In a dream scenario I’d quite like to see Slayer. They’re one band I’ve never seen in my life, although I’m not a particular speed metal aficionado.

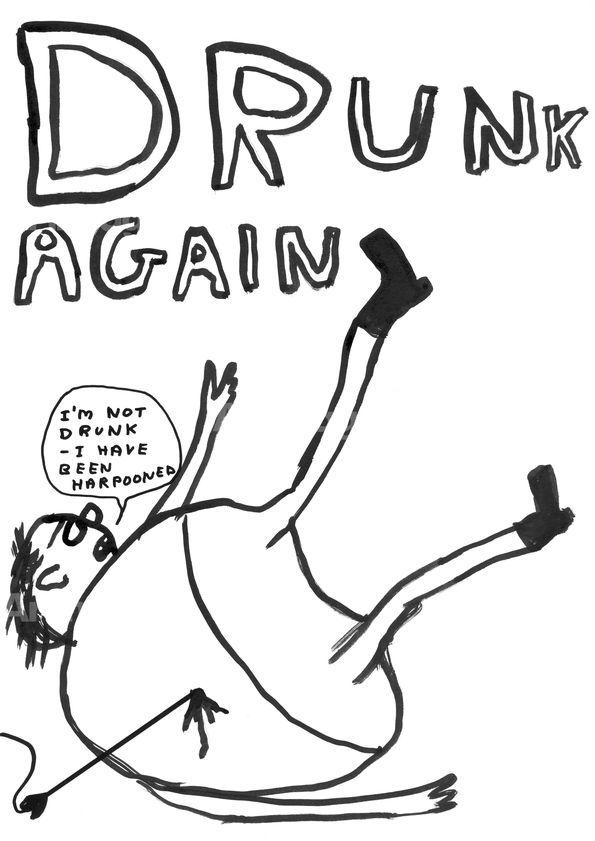

I Google Imaged your name and your drawing Drunk Again (pictured left) comes up top – what does that say about anything?

I’ve pondered Google Image many times. I’ve no idea. I certainly don’t feel it’s a seminal image in my oeuvre, put it that way. The thing that annoys me most about Google Image is it turns up pictures you haven’t done that are attributed to you and there’s no way of getting rid of them.

I’ve pondered Google Image many times. I’ve no idea. I certainly don’t feel it’s a seminal image in my oeuvre, put it that way. The thing that annoys me most about Google Image is it turns up pictures you haven’t done that are attributed to you and there’s no way of getting rid of them.

Do you have a favourite colour?

I think it’s probably a very vivid rose pink. It’s the colour that I seem to use a lot when I’m making paintings, a very vivid magenta. There’s a colour you can get called perfect pink that I think probably isn’t very archivally sound, meaning it will fade over time, but, yeah, I’d go for perfect pink.

Where is the oddest place art has taken you?

Aspen, Colorado is a pretty weird place. It’s a small town in the mountains where rich people go skiing. It has a population of 8,000 yet they have an art museum there. It’s like St Moritz in Switzerland which is another place on the art trail. The reason why you end up going there is because rich people live there, so you’re there to hawk your wares to the people who are responsible for the terrible economic situation we’re in.

How do you find having to describe your art to people like me?

I guess it’s become normal. My first moment in the sun was more than 20 years ago now. When you are an artist, you’re constantly having conversations with people who don’t know anything about art. They might ask you, for example, to tell them what conceptual art is – and I think I should be able to tell them. If you’re a professional and involved in the art world for your entire adult life, as well as your education, you should be able to have those conversations and be comfortable. More recently I’ve started to spend a lot of time in East Devon. My wife has a little house there, so we go there and hang out in the village pub. They’ve cottoned on to the fact I’m a well-known artist, looked me up on the internet and say, “That’s rubbish! What’s that all about?” So you have these conversations with people. You can’t insulate yourself from them. Ultimately it’s valuable to talk about the work: the context is half the work.

Overleaf: David Shrigley introducing Brighton Festival 2018