“Doing work” is the phrase that inmates of California’s New Folsom Prison have adopted to describe the group psychotherapy sessions that have been run there for more than 15 years now. Given that Folsom is a Level-4 penitentiary, in which murder is the least of the convictions for those imprisoned, most of whom will remain locked up there for the rest of their lives, issues of access and trust must have been as challenging as any documentary-maker could expect to encounter.

How The Work co-director Jairus McLeary came to resolve them is a story in itself (of which more later), but the fact that such trust was earned, in spades, is clear from every moment of his remarkable film. The Work is astonishing for many things, not least the degree to which it overturns our expectations of what a prison documentary might be. The inmates whose stories it partially tells may have been convicted of all manner of violent crimes, and were caught up in a gangland system in which extreme displays of masculinity were essential, but the predominant impression McLeary’s film leaves us with is of empathy, understanding, even gentleness (look out for a late scene in which that word features: how revealing it is!).

The moments of surrender to emotion sear viscerally

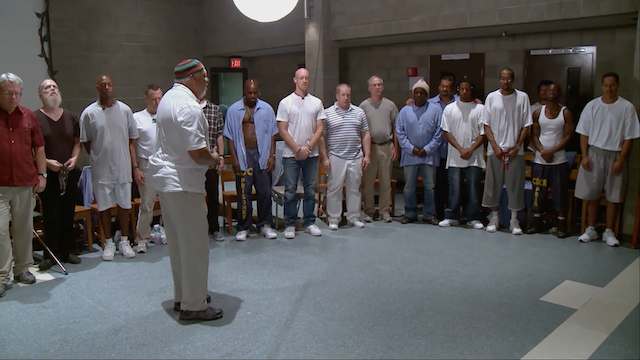

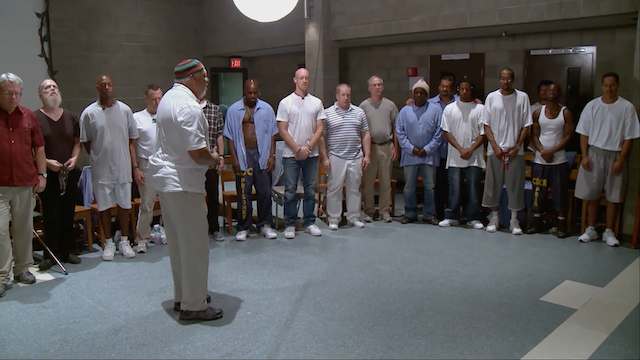

The Work follows the experience of participants in an intensive four-day therapy programme that is run at Folsom twice a year: they include outsiders, who have volunteered to join the therapy sessions, and inmates with the same motivations, as well as a range of facilitators, all of whom have been through the course before. Apart from the daily scenes of the incomers arriving at and leaving the facility (pictured below), the entire action is set in the prison chapel, which seems to accommodate around 60-80 men, divided variously into groups and sub-groupings; they enter an “Inside Circle”, reflecting the spatial arrangement of their interactions (lower picture). (The programme appeared at the end of the 1990s, and is coordinated by the Inside Circle Foundation, its motto “Helping prisoners and parolees heal from the inside”.)

Three incomers – bartender Charles, museum worker Chris, and teaching assistant Brian – are the film’s immediate subjects from outside. They come with issues that they feel they need to address, but without any certainty as to how things may proceed (degrees of scepticism are allowed all round). The insiders may be slightly less clearly delineated – though Vegas, Dante and Dark Cloud leave unforgettable impressions – and, having been through the course before, are the experienced ones, the guides (another expectation confounded?). The contrast between different worlds is every bit as acute for the insiders: in their everyday prison routine, gang allegiances – we hear from Crips and Bloods, Aryan Brothers and the Native American Brotherhood – remain absolute, every encounter involving group loyalty. Beyond the chapel walls, in the prison yard, the admissions of vulnerability we witness here would be unthinkable, if not fatal, as would be the ability shown to engage so empathetically with erstwhile enemies.

The contrast between different worlds is every bit as acute for the insiders: in their everyday prison routine, gang allegiances – we hear from Crips and Bloods, Aryan Brothers and the Native American Brotherhood – remain absolute, every encounter involving group loyalty. Beyond the chapel walls, in the prison yard, the admissions of vulnerability we witness here would be unthinkable, if not fatal, as would be the ability shown to engage so empathetically with erstwhile enemies.

The moments of surrender to emotion sear viscerally, the acuity with which these individuals talk of their circumstances no less so. We move between more controlled discussions into instances that involve confrontation with the past, a journey accompanied by extreme grief and frantic energy. These outpourings are met with a support that is literally physical, as bodies move in a mass across the floor, or writhe in heaps on the ground to restrain eruptions of feeling. It’s interspersed, cathartically and necessarily, with moments of joking and laughter. The particular issue that comes up most powerfully in the four days depicted in the film is that of fathers and sons – fathers whose absence, physical and/or emotional, from the childhoods of their offspring has continued the destructive patterns by which they themselves were forged.

It’s clear, however, that another four days might have brought up different themes entirely, making The Work that rare thing, a documentary which, though it clearly involved absolute planning and preliminary engagement, evolved in a completely uncharted environment. This DVD release gives valuable perspective on the process, a “framing” of the kind mentioned in the film itself: what we see on screen seems almost completely unmediated. The main extra is the press conference from this year's Sheffield Documentary Festival (where The Work won the Audience Award), telling us something of how the film came about. Joined by his co-producer brothers Eon and Miles, Jairus McLeary recalls how he came to Folsom, through their father James, who had grown up in similar gangland circumstances to the prison inmates, albeit in Chicago (McLeary Sr. is now a psychologist, and CEO of Inside Circle). Jairus, who also contributes a booklet essay, first participated in “The Work” in 2003 and has since been through it many times; he made sure that all crew members also took part, which must have paid off, notably in the ease with which cinematographer Arturo Santamaria works: assisted by a team of assistants, his roving cameras capture, seemingly effortlessly, the fluid circumstances of the sessions.

The main extra is the press conference from this year's Sheffield Documentary Festival (where The Work won the Audience Award), telling us something of how the film came about. Joined by his co-producer brothers Eon and Miles, Jairus McLeary recalls how he came to Folsom, through their father James, who had grown up in similar gangland circumstances to the prison inmates, albeit in Chicago (McLeary Sr. is now a psychologist, and CEO of Inside Circle). Jairus, who also contributes a booklet essay, first participated in “The Work” in 2003 and has since been through it many times; he made sure that all crew members also took part, which must have paid off, notably in the ease with which cinematographer Arturo Santamaria works: assisted by a team of assistants, his roving cameras capture, seemingly effortlessly, the fluid circumstances of the sessions.

The filming took place in 2009 after which, though it’s not made explicit here, the McLearys clearly hit a post-production hiatus, resolved only when British co-director Gethin Aldous came on board in 2015. He was accompanied, not least, by editor Amy Foote: the full material shot was presumably enormous, including extensive formal pre-interviews with the founders of Inside Circle which, given the intensity of the direct material, were never used.

The immediacy of the experience is such that contemplation comes only later. We are left to wonder where exactly the concept behind “The Work" came from. A prison riot at Folsom in 1997, which was followed by a seven-month lock-down, may have played a part in affecting the attitudes of the authorities. There’s mention of the Inside Circle founders being influenced by the writings of Viktor Frankl, the Austrian psychiatrist (and Holocaust survivor), while the more extreme moments of emotional release hint at Arthur Janov’s Primal Therapy. But finally this is a profoundly human-to-human experience, one which offers, in the bleakest of environments, a sense of hope against hope. Among the motivations for prisoners to take part is that it may influence their chances for parole: over its history, some 40 or so have been released in such a way. Watching The Work, you won't forget one of its inmate-participants, Vegas – he is now one of them.

Overleaf: watch trailers for The Work

The recurrent figure in Tavernier’s pantheon is Jean Gabin, the French acting icon from the 1930s through to the early 1960s, much more subtle than Depardieu in his depiction of the ordinary Frenchman. As Tavernier demonstrates with many carefully chosen clips, enhanced by an always eye-opening and thought-provoking commentary, Gabin was as fine an actor as any, not just the personification of a nation’s better self.

The recurrent figure in Tavernier’s pantheon is Jean Gabin, the French acting icon from the 1930s through to the early 1960s, much more subtle than Depardieu in his depiction of the ordinary Frenchman. As Tavernier demonstrates with many carefully chosen clips, enhanced by an always eye-opening and thought-provoking commentary, Gabin was as fine an actor as any, not just the personification of a nation’s better self.

The contrast between different worlds is every bit as acute for the insiders: in their everyday prison routine, gang allegiances – we hear from Crips and Bloods, Aryan Brothers and the Native American Brotherhood – remain absolute, every encounter involving group loyalty. Beyond the chapel walls, in the prison yard, the admissions of vulnerability we witness here would be unthinkable, if not fatal, as would be the ability shown to engage so empathetically with erstwhile enemies.

The contrast between different worlds is every bit as acute for the insiders: in their everyday prison routine, gang allegiances – we hear from Crips and Bloods, Aryan Brothers and the Native American Brotherhood – remain absolute, every encounter involving group loyalty. Beyond the chapel walls, in the prison yard, the admissions of vulnerability we witness here would be unthinkable, if not fatal, as would be the ability shown to engage so empathetically with erstwhile enemies. The main extra is the press conference from this year's Sheffield Documentary Festival (where The Work won the Audience Award), telling us something of how the film came about. Joined by his co-producer brothers Eon and Miles, Jairus McLeary recalls how he came to Folsom, through their father James, who had grown up in similar gangland circumstances to the prison inmates, albeit in Chicago (McLeary Sr. is now a psychologist, and CEO of Inside Circle). Jairus, who also contributes a booklet essay, first participated in “The Work” in 2003 and has since been through it many times; he made sure that all crew members also took part, which must have paid off, notably in the ease with which cinematographer Arturo Santamaria works: assisted by a team of assistants, his roving cameras capture, seemingly effortlessly, the fluid circumstances of the sessions.

The main extra is the press conference from this year's Sheffield Documentary Festival (where The Work won the Audience Award), telling us something of how the film came about. Joined by his co-producer brothers Eon and Miles, Jairus McLeary recalls how he came to Folsom, through their father James, who had grown up in similar gangland circumstances to the prison inmates, albeit in Chicago (McLeary Sr. is now a psychologist, and CEO of Inside Circle). Jairus, who also contributes a booklet essay, first participated in “The Work” in 2003 and has since been through it many times; he made sure that all crew members also took part, which must have paid off, notably in the ease with which cinematographer Arturo Santamaria works: assisted by a team of assistants, his roving cameras capture, seemingly effortlessly, the fluid circumstances of the sessions.

Louis has a pain in his leg; as it worsens, he is confined to bed; eventualy gangrene sets in. The process of dying is slow and laboured, and the principle action – hardly the right way of putting it – comes from the deliberations of the doctors who discuss and administer a variety of treatments (pictured above). However, Serra does achieve one scene in which the awareness of approaching death becomes transfixingly clear, as Léaud stares into the camera, unforgettably locking the audience’s gaze. It's a stark moment of contrast in mood, the breach of the fourth wall emphasised by the accompaniment of Mozart’s Great C minor Mass (there is no other incidental music in the film).

Louis has a pain in his leg; as it worsens, he is confined to bed; eventualy gangrene sets in. The process of dying is slow and laboured, and the principle action – hardly the right way of putting it – comes from the deliberations of the doctors who discuss and administer a variety of treatments (pictured above). However, Serra does achieve one scene in which the awareness of approaching death becomes transfixingly clear, as Léaud stares into the camera, unforgettably locking the audience’s gaze. It's a stark moment of contrast in mood, the breach of the fourth wall emphasised by the accompaniment of Mozart’s Great C minor Mass (there is no other incidental music in the film).

But this is also nature, in the sheer physical sense, at its most impressive (pictured above). The craggy coast around the cluster of houses that makes up the isolated village rises up towards spectacular mountains, which somehow dwarf any human activity with their scale. In summer, as the light stretches around the clock, the beauty is awesome, memorably captured in Norwegian cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grøvlen’s widescreen vistas. But we sense that when winter comes – Heartstone closes as the first dusting of snow falls – the cold isolation of the place will be as complete as the luminous airiness with which it seasonally alternates.

But this is also nature, in the sheer physical sense, at its most impressive (pictured above). The craggy coast around the cluster of houses that makes up the isolated village rises up towards spectacular mountains, which somehow dwarf any human activity with their scale. In summer, as the light stretches around the clock, the beauty is awesome, memorably captured in Norwegian cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grøvlen’s widescreen vistas. But we sense that when winter comes – Heartstone closes as the first dusting of snow falls – the cold isolation of the place will be as complete as the luminous airiness with which it seasonally alternates. The father has gone off with a younger woman, and any sympathy for their mum's tentative attempts to find someone to date in this backwater is notably lacking. We see what it involves for her when the adults get together for the village-hall dance – a thrash, if ever there was one – and her attention falls on the outsider Sven (Søren Malling, a visitor in every sense: he’s Torben, from Borgen). Nevertheless there’s a sense of tough-love affection in this family unit that is finally reassuring, as well as an element of comedy to the sisters, Hafdis (Ran Ragnarsdottir) particularly; she writes poetry of Plath-like intensity that she reads out at meals.

The father has gone off with a younger woman, and any sympathy for their mum's tentative attempts to find someone to date in this backwater is notably lacking. We see what it involves for her when the adults get together for the village-hall dance – a thrash, if ever there was one – and her attention falls on the outsider Sven (Søren Malling, a visitor in every sense: he’s Torben, from Borgen). Nevertheless there’s a sense of tough-love affection in this family unit that is finally reassuring, as well as an element of comedy to the sisters, Hafdis (Ran Ragnarsdottir) particularly; she writes poetry of Plath-like intensity that she reads out at meals.

But this absorption means that he fails to notice approaching rapids in the river, and the next thing we know his body is found by two Chinese girls who are hiking through the thick forest, obviously very lost indeed from their Santiago pilgrimage route. From here on the tone of Rodrigues’ film moves ineffably towards the bizarre and spiritually highly-strung: when Fernando wakes up next, he’s been trussed up with ropes, à la St Sebastian, by the pilgrims. Narrowly escaping that one, his attempts to find his way back to civilisation (whatever that might mean in such a context) seem doomed, every new encounter stranger than the last.

But this absorption means that he fails to notice approaching rapids in the river, and the next thing we know his body is found by two Chinese girls who are hiking through the thick forest, obviously very lost indeed from their Santiago pilgrimage route. From here on the tone of Rodrigues’ film moves ineffably towards the bizarre and spiritually highly-strung: when Fernando wakes up next, he’s been trussed up with ropes, à la St Sebastian, by the pilgrims. Narrowly escaping that one, his attempts to find his way back to civilisation (whatever that might mean in such a context) seem doomed, every new encounter stranger than the last.

This is highlighted in the film’s final moments, three gut-wrenching minutes made all the more affecting because they follow 90 minutes of relationship-building. The story here is the people Dina and Scott are, not what they’ve been through or what they’ve been diagnosed with. The approach works: somewhere along the way you begin really caring for these characters.

This is highlighted in the film’s final moments, three gut-wrenching minutes made all the more affecting because they follow 90 minutes of relationship-building. The story here is the people Dina and Scott are, not what they’ve been through or what they’ve been diagnosed with. The approach works: somewhere along the way you begin really caring for these characters.

Based on a hugely popular novel,

Based on a hugely popular novel,