It’s about time Juliette Binoche and Claire Denis teamed up: the legendary French actress, Gallic film royalty known by her countrymen and women as La Binoche, with one of the country’s most unique directors, both talented and formidable women who have very much forged their own paths in the cutthroat world of the film industry.

Just like waiting for a bus, there are now two collaborations between them, made in quick succession: the second, a science fiction co-starring Robert Pattinson, is in post-production. The Arts Desk met Binoche in Paris to speak about the first.

Let the Sunshine In has the ring of schmaltzy romcom or some feel-good, self-help musical; it hardly bodes well. And yet this is Denis (pictured below), whose work – Chocolat, Beau Travail, White Material, 35 Shots of Rum, the aptly named Bastards – doesn’t dabble in popcorn frivolity, but tangible, often painful reality; even her vampire film Trouble Every Day had the disturbing stench of believability.

Thus the new film, which involves a middle-aged, divorced artist, Isabelle (Binoche), and her desperate search for ‘one real love’. Through the course of the movie she considers numerous suitors, each clearly unsuitable, at least two of them married, Isabelle throwing her heart, soul and body at them, with humiliation and disappointment the reward. Though she has a 10-year-old daughter, we see the girl onscreen just once, as she’s driven away by her father. Isabelle’s focus is herself and her fear that her love life is behind her; and for someone who is seemingly successful and intelligent, and old enough to know better, she’s rather foolish about it all.

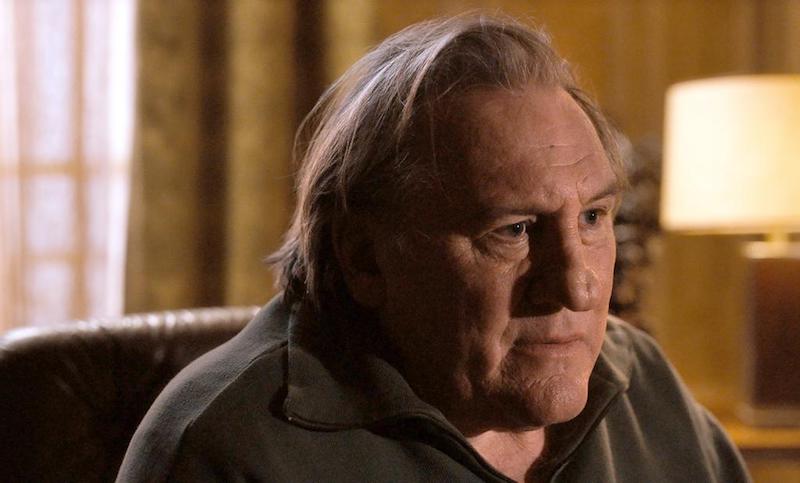

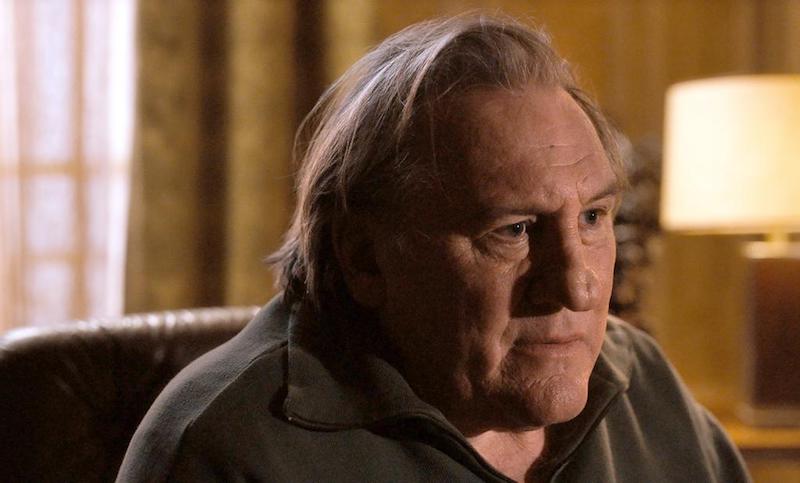

With its romantic theme, Let the Sunshine In is closest to Denis’ Vendredi Soir, an offbeat, touching love story involving a man and a woman who meet in a traffic jam. But the new film is edgier, more pessimistic and, actually, funnier. Denis has co-written the script with the French author Christine Angot, and the pair are so on the money in their characterisations and situations that the result is variously sad, discomforting and enjoyably ridiculous, with Isabelle and her amours equal targets; the writers also shoot a few well-aimed arrows at the pomposity of the Parisian art world. Denis has surrounded her star with some accomplished male foils, not least Gérard Depardieu as a clairvoyant to whom Isabelle turns in the film’s wondrously bonkers final scene. This is another first, since the pair haven’t acted together before, the encounter lent added spice by the knowledge of Depardieu’s unsolicited criticism of Binoche in 2010, when he told a journalist: “I would really like to know why she has been so esteemed for so many years. She has nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

Denis has surrounded her star with some accomplished male foils, not least Gérard Depardieu as a clairvoyant to whom Isabelle turns in the film’s wondrously bonkers final scene. This is another first, since the pair haven’t acted together before, the encounter lent added spice by the knowledge of Depardieu’s unsolicited criticism of Binoche in 2010, when he told a journalist: “I would really like to know why she has been so esteemed for so many years. She has nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

She shows plenty opposite him, but that’s no surprise. And this is Binoche’s show. Gaudily dressed in mini-skirt and leather boots, her make up overdone, invariably on the verge of welling up, her Isabelle teeters on the edge of nonsense. Yet Binoche also reveals shards of integrity, intelligence, passion and some self-deprecating humour in her character. Despite her spectacular signature laugh, the actress has done relatively little comedy, though this confirms a gift for it.

The suggestion is of a full-blooded individual thrown off-kilter by romantic panic. It’s a raw, real, winning performance, in an off-beat, female-centred film, talky in that way that many failing relationships are, and speaking quite boldly about the problems that women of a certain age may have to find love, or at least a half-decent male companion. DEMETRIOS MATHEOU: What attracted you to this?

DEMETRIOS MATHEOU: What attracted you to this?

JULIETTE BINOCHE: I know something about the difficulty of love. I was touched by the writing, because it's rare to have a script that is so well-written, which feels real. And it was my first time with Claire Denis. To have the complicity of those two women, Claire and Christine, putting together those fragments of love, was very appealing.

But we didn't know it was going to be that funny. When I saw the film the first time people were laughing a lot, and I was laughing as well. The second time I saw it I was crying. The film can be taken very differently. It depends how you feel, what kind of distance you have.

Why do you think the character is so unlucky in love?

I think she's trying to find a solution outside of herself, for her lack of love, her need, which is what we all tend to do. What I've learned going through life is that you've got to find some place in you that is at peace, first, in order to then attempt a relationship. But it takes courage. And it takes time also.

I don't believe that suddenly everything is resolved because you're in a couple. When I was a young lover I thought you really had to meet your alter ego, the other part of yourself. Now I don't think that exists. True love, the one that stays forever, is in you. It takes a while to understand that. That's why you suffer so much. When you're not expecting everything from the other person, then I think that things can happen, in a different way.

The film also touches on the way that social differences can affect relationships.

That's a big question, and not an easy one. Can love survive social differences? It’s a very important subject to the writer, Christine. She had been through that kind of situation. So what she writes about it is very explored, lived, and I felt that in the writing. For the man who I meet when dancing, Claire decided to cast Paul Blaine, because he was more fragile in a way, and that was very intelligent. I felt the difference somehow. It brings something special to the film.

What did you bring of yourself to this character?

Everything.

The film ends with Depardieu’s clairvoyant (pictured below) Have you ever looked for those kinds of answers?

I've been to a psychic, in my twenties especially. I understand the thirst for it, wanting to know the truth. When you're hesitating about something or someone, you think it's going to help you. It does help in a way, if it defines what you're feeling already, but I find it dangerous, because anybody can tell you anything and then you go for it. It's all crazy, I think. Your belief system, that's what's most important. You need to trust your intuition.  Did Depardieu apologise by the way, for his criticism of you? Any humble pie on the set?

Did Depardieu apologise by the way, for his criticism of you? Any humble pie on the set?

No. But I didn't need an apology. Actually three months after his declaration I saw him by accident in the street. I went to him and I took him in my arms and I said ‘Gerard why are you so mean to me? What have I done to you?’ And he said 'No, no, no, I'm saying stupid things, don't believe them.’

He then said, ‘I'm fed up that you're working with perverse directors’. I asked him who he was talking about. And he said, ‘Well, Leos Carax and Haneke’. But then he said that [Haneke's] The White Ribbon is actually a good film. After we separated I thought, ‘Well he's made films with Pialat, he's made films with Blier! I think he was just caught out by meeting me like that.

You know, the first time I ever went on a film set it was Danton [which starred Depardieu, in 1983]. I was just 18, still in high school. A friend of my father's was working on the film and invited me to watch the shooting. I was excited. And Gerard came to me, very open, and he said ‘What are you doing here?’ I said I was to be an actress. He said, ‘Work on your classics’. He was very cute and generous. So when suddenly years later his declaration happened, I was shocked.

So many of the scenes in the film feel raw, immediate. Did you try different ways of playing them?

No, because we didn't have a lot of time. We shot the film in five weeks. Very quick. Even the Depardieu scene is one day. So I had to make sure that I knew my text. Then you just throw yourself into the scene.

How did you find the experience of working with Claire Denis?

It was beautiful. It was like watching a painter. It was not always the logical way, she would go one frame, one shot at a time, working in steps, more than having the general idea of it and knowing exactly which shot she wanted. It was moment to moment, which I liked. I was learning by seeing her see.

Also she has such respect for human beings. She loved all the characters. There was no hierarchy, it was a very moving way of going through a film.

And you’re working with her again?

Yeah, in one year we've made two films together. That’s never happened to me. Science fiction. Nine actors in this space, coming from very different places. It was exciting.

Is there a different spirit on set when working with a female director?

I've never really felt that, because you work with the sensibility and the intelligence of someone. The complicity is not sexual. There's a seduction that's happening between the actors and director, but the seduction has to do with the fact that we need to create this fire between us, so that we can go into the work together, see if we need another take, never losing time. You’ve been working now for some 30 years. How do you stay challenged or engaged?

You’ve been working now for some 30 years. How do you stay challenged or engaged?

I’m always trying to find something new, that I’ve never done before. Repetition feels like near death. Creation is about the new. Something is going to happen but you don't know what. So you're moving towards that moment.

Life gives me things, I say yes or no. Or I create encounters. Abbas Kiarostami [Certified Copy, pictured above] and Bruno Dumont [Camille Claudel 1915, Slack Bay] were directors I was dreaming about working with – so you have to pick up the phone or go to that person and say it. Sometimes it's that’s simple.

So what was the challenge in this film?

I think it was the writing, because it was already there, I just had to put my hand in the glove. That was a new kind of situation for me. Most of the time we are really trying hard as actors because the writing, the script is not precise. But with Christine it's been felt, it's been lived.

When a script is not well written it's usually because it comes out of the head and not out of experience, and you really feel it when you’re acting and learning the lines. But on this one I felt lifted by the writing, and by the actors.

You’ve done nudity before, but not often, and this film goes straight into a long nude scene. Are you ever comfortable with such scenes?

You kidding me, I'm fucking scared! But I'm doing it. I think you've got to go into your fear, that's the challenge of it. So you can learn something from it, and change the fear eventually. Singing is very frightening to me, because I’m not a singer, and I’ve discovered how to put emotion into the singing. And the same with dance. But I'm frightened like anybody.

- Let the Sunshine In is released in cinemas on 20 April

@dem2112

Overleaf: watch the trailer to Let the Sunshine In

Fontaine has filled in that gap by positing an imagined concept that the Louis figure, here named Marvin Bijou – the awkwardness of that surname, translated as “Jewels”, seems horribly ironic for a context that is anything but sparkling – found his path out of that desolate early milieu through theatre. Early encouragement from a sympathetic schoolteacher is fortuitously followed by engagement with an intuitive stage director-coach, who draws Marvin both out of himself and into the Parisian gay scene. Never entirely losing his shyness, his involvement in that culture grows, encouraged by a largely benevolent sugar daddy figure who moves in circles of which the youth could once barely have dreamed.

Fontaine has filled in that gap by positing an imagined concept that the Louis figure, here named Marvin Bijou – the awkwardness of that surname, translated as “Jewels”, seems horribly ironic for a context that is anything but sparkling – found his path out of that desolate early milieu through theatre. Early encouragement from a sympathetic schoolteacher is fortuitously followed by engagement with an intuitive stage director-coach, who draws Marvin both out of himself and into the Parisian gay scene. Never entirely losing his shyness, his involvement in that culture grows, encouraged by a largely benevolent sugar daddy figure who moves in circles of which the youth could once barely have dreamed.

It’s their shared interest in their subjects – hardly the right word, when collaboration is so close – that makes this pairing ideal; these are not artists working on their own, but creators of events. “To meet new faces,” is how Varda expresses the resolve behind their road trip, its destinations better caught by the film’s French title, Visages Villages. No big city monotony here, rather an exploration of rural France, its singularities and personalities relished to the full.

It’s their shared interest in their subjects – hardly the right word, when collaboration is so close – that makes this pairing ideal; these are not artists working on their own, but creators of events. “To meet new faces,” is how Varda expresses the resolve behind their road trip, its destinations better caught by the film’s French title, Visages Villages. No big city monotony here, rather an exploration of rural France, its singularities and personalities relished to the full. By loose extension, art becomes a catalyst that can transform the everyday. Asked by one railwayman why JR has pasted images of Varda’s eyes (and toes, too) onto the sides of chemical-storage train tankers, she replies that it is to endorse the “power of imagination”. We may perhaps wonder whether there is nevertheless an elitist concept involved somewhere, in this conscious idea that “art is for everyone”, especially when promulgated by France’s generous funding regime. But Varda’s film brings home how that can never be the case when everyone is involved (the film’s crowdfunding element is surely as appropriate here as the concept has ever been).

By loose extension, art becomes a catalyst that can transform the everyday. Asked by one railwayman why JR has pasted images of Varda’s eyes (and toes, too) onto the sides of chemical-storage train tankers, she replies that it is to endorse the “power of imagination”. We may perhaps wonder whether there is nevertheless an elitist concept involved somewhere, in this conscious idea that “art is for everyone”, especially when promulgated by France’s generous funding regime. But Varda’s film brings home how that can never be the case when everyone is involved (the film’s crowdfunding element is surely as appropriate here as the concept has ever been).

These are big set pieces that are beautifully recreated here. Godard's presence at the street protests is ironically marked by the recurring joke of how he breaks his glasses over and over again in the demonstrations (a nice late line in Stacy Martin’s voice-over suggests that it was the rising optician costs that finally stopped him joining them). More significantly, he was rejected by the student protestors, not least for arguing, in relation to Palestine, that the “Jews are the new Nazis” (plus ça change...). Intent on changing his creative direction, Godard was flummoxed by people coming up to him to ask why he wasn’t making movies like Breathless anymore (even a policeman, after a fracas, confesses how much he loved Contempt).

These are big set pieces that are beautifully recreated here. Godard's presence at the street protests is ironically marked by the recurring joke of how he breaks his glasses over and over again in the demonstrations (a nice late line in Stacy Martin’s voice-over suggests that it was the rising optician costs that finally stopped him joining them). More significantly, he was rejected by the student protestors, not least for arguing, in relation to Palestine, that the “Jews are the new Nazis” (plus ça change...). Intent on changing his creative direction, Godard was flummoxed by people coming up to him to ask why he wasn’t making movies like Breathless anymore (even a policeman, after a fracas, confesses how much he loved Contempt).

Denis has surrounded her star with some accomplished male foils, not least Gérard Depardieu as a clairvoyant to whom Isabelle turns in the film’s wondrously bonkers final scene. This is another first, since the pair haven’t acted together before, the encounter lent added spice by the knowledge of Depardieu’s unsolicited criticism of Binoche in 2010, when he told a journalist: “I would really like to know why she has been so esteemed for so many years. She has nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

Denis has surrounded her star with some accomplished male foils, not least Gérard Depardieu as a clairvoyant to whom Isabelle turns in the film’s wondrously bonkers final scene. This is another first, since the pair haven’t acted together before, the encounter lent added spice by the knowledge of Depardieu’s unsolicited criticism of Binoche in 2010, when he told a journalist: “I would really like to know why she has been so esteemed for so many years. She has nothing. Absolutely nothing.” DEMETRIOS MATHEOU: What attracted you to this?

DEMETRIOS MATHEOU: What attracted you to this? Did Depardieu apologise by the way, for his criticism of you? Any humble pie on the set?

Did Depardieu apologise by the way, for his criticism of you? Any humble pie on the set? You’ve been working now for some 30 years. How do you stay challenged or engaged?

You’ve been working now for some 30 years. How do you stay challenged or engaged?