Dunkirk review - old-fashioned filmmaking on the grandest scale

Christopher Nolan's evacuation epic lets Spitfires and 'Nimrod' do the talking

What is the Dunkirk spirit? It has been so thoroughly internalised by the national psyche that, 77 years on, it’s as much a brand, a meme or a slogan as the product of a historical fact: that at the start of World War Two 330,000 soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force, cornered on a French beach, strafed and bombed by the Luftwaffe, were ferried to safety by a plucky flotilla of pleasure barques and rickety fishing boats. Triumph snatched from the jaws of unimaginable catastrophe.

How do you capture that spirit on film? People keep trying. ITV made a three-part docudrama in 2004. It is the central event in the film version of Ian McEwan’s Atonement. Earlier this year there was The Nancy Starling, the film-within-a-film that lovingly spoofed the stiff-upper-lipped wartime propaganda in Their Finest. The Nancy Starling was a boat captained by a nuggetty old seadog played by Bill Nighy. Mark Rylance, at the wheel of the Moonstone, plays virtually the same character in Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk: the embodiment, in a suit and neat tie, of an English refusal to buckle in the face of the grimmest odds. “There’s no hiding from this, son,” says Mr Dawson in a loamy Dorset burr when urged to turn back from danger. “We’ve got a job to do.” Nolan’s Dunkirk is an epic vignette, a story that starts after the beginning and finishes before the end. Fionn Whitehead’s pretty young Tommy (pictured below) escapes from pounding rifle fire in sandbagged Dunkirk and makes it onto the beach where thousands form lines to get back home. In comes a German bomber dropping a petrifying column of bombs which detonate like skimmed stones, spitting up huge booming fountains of sand. The queues disperse, only to reform in a reassuringly British way: we’ll face Armageddon in an orderly fashion, thank you very much.

Nolan’s Dunkirk is an epic vignette, a story that starts after the beginning and finishes before the end. Fionn Whitehead’s pretty young Tommy (pictured below) escapes from pounding rifle fire in sandbagged Dunkirk and makes it onto the beach where thousands form lines to get back home. In comes a German bomber dropping a petrifying column of bombs which detonate like skimmed stones, spitting up huge booming fountains of sand. The queues disperse, only to reform in a reassuringly British way: we’ll face Armageddon in an orderly fashion, thank you very much.

Tommy isn’t a queuer. His desperation to get off the beach finds him collaring another soldier, grabbing a casualty on a stretcher and barging through crowds of men onto the Mole, the jetty jutting out into the tide to receive naval vessels. Tommy faces drowning any number of times in the course of his homeward odyssey. As ships list, buckle, snap in two - or in the case of one boat which slowly sinks in the rising tide as bullet holes pepper the hull - Nolan recreates underwater hells with knuckle-gnawing realism. Meanwhile up in the skies Tom Hardy (pictured below) and Jack Lowden play an imperturbable pair of Spitfire aces who dogfight their way to the rescue. These airborne sequences are the film’s most beautiful and thrilling: the pilot’s eye view of tipsily swaying wings, Messerschmitts in the rear mirror, the blue briny main below and a black plume of smoke rising from the French coast. One of the boats the pilots can see down below is the Moonstone, crewed by Mr Dawson's son (Tom Glynn-Carney) and a young boy (Barry Keoghan) who might have walked out of the script of The Nancy Starling. They soon encounter the hull of an upturned ship, recently torpedoed by a U-boat, atop which Cillian Murphy sits like a shellshocked Robinson Crusoe.

Meanwhile up in the skies Tom Hardy (pictured below) and Jack Lowden play an imperturbable pair of Spitfire aces who dogfight their way to the rescue. These airborne sequences are the film’s most beautiful and thrilling: the pilot’s eye view of tipsily swaying wings, Messerschmitts in the rear mirror, the blue briny main below and a black plume of smoke rising from the French coast. One of the boats the pilots can see down below is the Moonstone, crewed by Mr Dawson's son (Tom Glynn-Carney) and a young boy (Barry Keoghan) who might have walked out of the script of The Nancy Starling. They soon encounter the hull of an upturned ship, recently torpedoed by a U-boat, atop which Cillian Murphy sits like a shellshocked Robinson Crusoe.

As Nolan’s script commutes between land, sea and air, it takes the shape of a jagged triptych, a trinity of storylines seeking the oneness of redemption. The three elements do in the end coalesce, but not without some jarring continuity jumps as the scene darts hither and thither, including between night in Dunkirk and day over the seas. Anyone hoping to be guided through all this morass of detonations and drownings by the handrail of dialogue, the nuance and shade of human drama, will have to go whistle. Dunkirk is not about characters but character. While the young cast of mostly unknowns are hurled about like swimming skittles, Nolan has shrewdly cast venerated older actors to embody a single signature attitude. And his stars deliver, even when he overuses the oldest trick in the storytelling playbook, closing in on the faces of Rylance or Kenneth Branagh (pictured below) as a naval commander as their eyes take in coming danger. When Branagh slowly blinks at the diving approach of a Heinkel, it sums up the film’s thespian rule of thumb: the eyes have it.

Anyone hoping to be guided through all this morass of detonations and drownings by the handrail of dialogue, the nuance and shade of human drama, will have to go whistle. Dunkirk is not about characters but character. While the young cast of mostly unknowns are hurled about like swimming skittles, Nolan has shrewdly cast venerated older actors to embody a single signature attitude. And his stars deliver, even when he overuses the oldest trick in the storytelling playbook, closing in on the faces of Rylance or Kenneth Branagh (pictured below) as a naval commander as their eyes take in coming danger. When Branagh slowly blinks at the diving approach of a Heinkel, it sums up the film’s thespian rule of thumb: the eyes have it.

Much of what people say to one another (including Harry Stiles, who looks the part as a soldier in short back and sides) is drowned out by the clang of Hans Zimmer’s unrelenting soundtrack, a fusillade of yearning strings and kinetic thrums like the growl of an implacable engine. He deploys Elgar’s Nimrod early on, its plangent strains slowed down to a half-recognisable quarter time, and returns to it like a Wagnerian motif. Its most shameless appearance comes when Branagh spots Blighty’s pygmy trawlers through his binoculars, chugging to the rescue out of the sea mist. Nimrod swells, and the triggered heart obediently follows. This is old-fashioned filming on the grandest scale, and yet - mercifully light on SFX - it cannot encapsulate the vastness of the evacuation. There are hardly any ships and boats on screen, the Luftwaffe mainly stay away, and the 330,000 must be taken on trust. As for Tommy, the last time a leading man said quite so little was in The Artist. Only at the end does Fionn Whitehead have an outbreak of speechifying when on a train back from the coast he reads out the newspaper report quoting Churchill’s speech to the house: “we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be”.

This is old-fashioned filming on the grandest scale, and yet - mercifully light on SFX - it cannot encapsulate the vastness of the evacuation. There are hardly any ships and boats on screen, the Luftwaffe mainly stay away, and the 330,000 must be taken on trust. As for Tommy, the last time a leading man said quite so little was in The Artist. Only at the end does Fionn Whitehead have an outbreak of speechifying when on a train back from the coast he reads out the newspaper report quoting Churchill’s speech to the house: “we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be”.

As those hoary words, the oratorical coeval of Elgar, bloom freshly in the voice of hopeful youth, it is worth asking the big question about the timing of Dunkirk. Why this particular nostalgic story now? Why in 2017 revisit a modern national myth about the heroic retreat from continental Europe to the safety of our island redoubt, in which shambolic Brits wing it with blind pluck and keep-calm derring-do? One image in particular seems overtly to allude to the UK on the cusp of another darkest hour: the undercarriage of Hardy’s Spitfire creaking sclerotically into position so that this most British of icons can make a safe landing. There is every danger that Nolan's undeniably rousing homage may fall into the wrong hands.

Overleaf: watch the trailer to Dunkirk

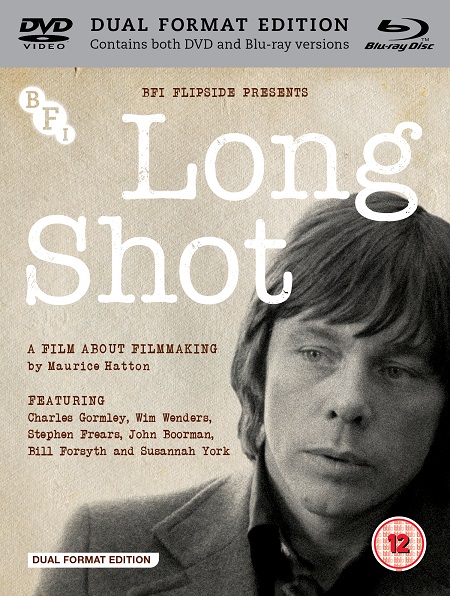

The duo becomes an unlikely trio with the appearance, for no particular good reason but very charmingly, of actress Annie (Anne Zelda). Various picaresque dashes around the Edinburgh streets follow, one in a car commandeered from Stephen Frears (credited as “Biscuit Man"). Gallerist Richard Demarco appears somewhat grouchily as himself, Alan Bennett turns in a brilliant cameo as a hilariously diffident doctor who, on being told that writing is a lonely profession, suggests meals on wheels. Susannah York gamely plays along: hearing that the female role is underdeveloped, she coolly replies, “So you came to me?”

The duo becomes an unlikely trio with the appearance, for no particular good reason but very charmingly, of actress Annie (Anne Zelda). Various picaresque dashes around the Edinburgh streets follow, one in a car commandeered from Stephen Frears (credited as “Biscuit Man"). Gallerist Richard Demarco appears somewhat grouchily as himself, Alan Bennett turns in a brilliant cameo as a hilariously diffident doctor who, on being told that writing is a lonely profession, suggests meals on wheels. Susannah York gamely plays along: hearing that the female role is underdeveloped, she coolly replies, “So you came to me?”

Nat doesn’t know about the sideline sales, and becomes fond of the young man, impressed by his baking skills and touched by his piety – Ayyash doesn’t get high on his own supply and is a devout Muslim. In another cross-cut sequence we see both men performing their particular ritual prayers in separate areas of the bakery. It’s all very well-meaning, hands-across-the-divide stuff with plenty of gags about Jewish and Muslim preconceptions about each other, but it pulls its punches. It would have been braver to have had Ayyash come from the Middle East rather than Africa.

Nat doesn’t know about the sideline sales, and becomes fond of the young man, impressed by his baking skills and touched by his piety – Ayyash doesn’t get high on his own supply and is a devout Muslim. In another cross-cut sequence we see both men performing their particular ritual prayers in separate areas of the bakery. It’s all very well-meaning, hands-across-the-divide stuff with plenty of gags about Jewish and Muslim preconceptions about each other, but it pulls its punches. It would have been braver to have had Ayyash come from the Middle East rather than Africa.