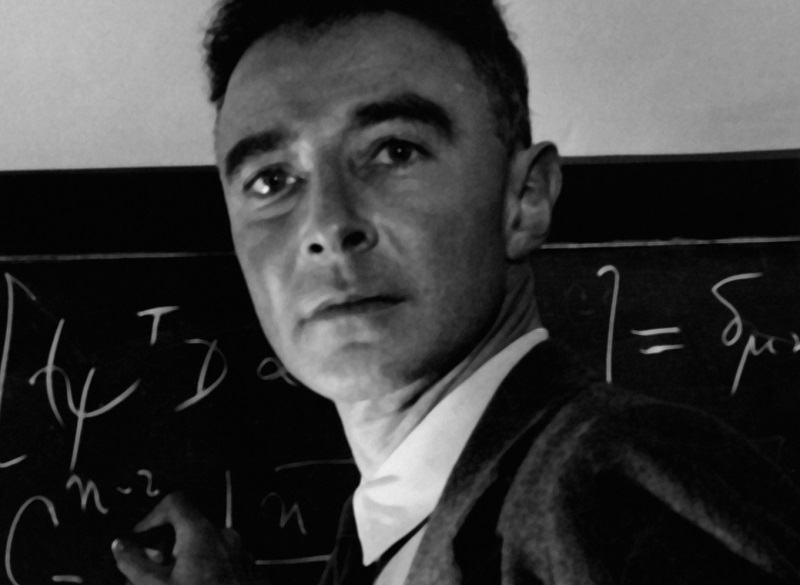

That the truth will always be so much bigger than we can comprehend is something I had to accept as I started to write Oppenheimer. There are so many sources, so much information, so many hundreds of books, declassified files, interviews and history. One biography of the man took its authors 25 years to write. And there are still the hidden thoughts that were never written down, conversations long forgotten by people now long dead. There have to be so many omissions that it is an impossible task to tell this "truth" over the course of one evening’s entertainment. And people have told this story before – there has been an opera, several TV series, movies, novels, comic books and plays – so why even bother?

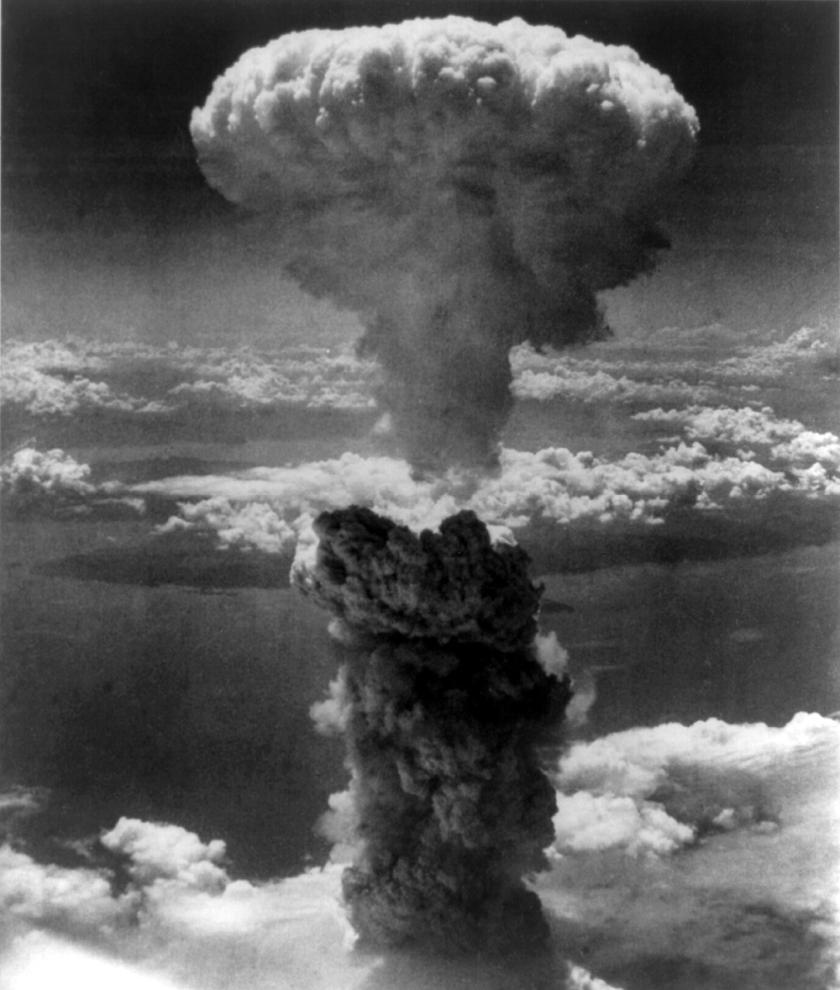

Artists and writers return to the story of Robert Oppenheimer, and indeed the entire Manhattan Project, because it functions as a creation myth for the modern world. The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki can be seen as the first acts of the Cold War – a posturing of power towards the Russians. In the treatment of Oppenheimer we can see the seeds of McCarthyism and the anti-Communist hysteria that came to define the 1950s. The surveillance culture that became so prominent throughout the second half of the 20th century, and continues to this day, can be traced back to those laboratories in Berkeley and New Mexico.

There is a concept in quantum theory known as complementarity. It was developed by Niels Bohr, one of the founding fathers of quantum mechanics (and a character in Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen). Put simply, it is the idea that two scientists, researching the same phenomena, could come to two entirely opposite, yet equally true, conclusions. It is perfectly reasonable for one scientist to conclude that light is made up of particles, for example, while the other discovers that light is constructed of waves – both answers are demonstrably true, neither are adequate. (Pictured below: director Angus Jackson with, right, playwright Tom Morton-Smith. Photograph by Keith Pattison)

In the play I use this idea to explain how it is possible that the Nazi atomic bomb programme never developed beyond some designs for a nuclear reactor, while the US and British project created the most devastating weapon that had ever been known. Both teams were working on the same problem, both projects boasted geniuses amongst their number - only one succeeded.

In the play I use this idea to explain how it is possible that the Nazi atomic bomb programme never developed beyond some designs for a nuclear reactor, while the US and British project created the most devastating weapon that had ever been known. Both teams were working on the same problem, both projects boasted geniuses amongst their number - only one succeeded.

The truth is huge and can never be captured, or even comprehended – in the same way that you will never be able to explain the internet to a cat. But glimpses of truth, glimpses of ideas and thoughts – these go some way to helping us to understand the world. The human brain is remarkable when it comes to joining the dots and filling in the gaps. I hope there are enough glimpses of the Manhattan Project, of Oppenheimer and of that horrific but arguably necessary weapon to make my play sufficiently thought-provoking and maybe even close to telling some small part of truth.

Add comment