Kafka and Jones, the names above this little shop of horrors, would be a marriage made in off-kilter theatreland had the Czech genius written any plays. He didn’t, so Nick Gill has made a well-shaped drama out of the assembled fragments of which The Trial consists. It offers an exhaustive role for Rory Kinnear, never offstage for the unbroken two-hour duration, and lets director Richard Jones revert from the warm humanity he’s most recently been unable to resist in Wagner’s The Mastersingers of Nuremberg and Puccini’s The Girl of the Golden West back to his favoured world of discomfort and compulsion immaculately choreographed.

On the travelator tonight we have assorted orange bins, lampshades with Titian Venus and Alsatian designs, china dogs, tables of photos from family groups to Charles Manson, beds, desks, doors all moving on and off in perfect synchonicity with David Sawer’s deliberately horrid organ score. Bathed at first in an uncomfortable orange light, courtesy of Jones's resident genius Mimi Jordan Sherin in cahoots with designers Miriam Buether and Nicky Gillibrand, the rest of the scenery is the audience banked either side. Many of its members look not so much like courtroom public as victims lined up against pinewood boards waiting for their mugshots – and on the first night there were some seriously good actors in the crowd seemingly playing up to expectations.

The alienated not-quite-innocent revealed when the giant keyhole rises up from the travelator is Josef K (Kinnear pictured left), gawking at lapdancer Tiffany. Speaking on waking in a stream of consciousness that seems part baby talk, part James Joyce – a clever if tricksy way of transforming the novel’s third person narrative – he’s not an easy subject for Kinnear to handle. Soon, though, the switch to mundane everyday language hints at a virtuosity that only occasionally makes itself obvious.

The alienated not-quite-innocent revealed when the giant keyhole rises up from the travelator is Josef K (Kinnear pictured left), gawking at lapdancer Tiffany. Speaking on waking in a stream of consciousness that seems part baby talk, part James Joyce – a clever if tricksy way of transforming the novel’s third person narrative – he’s not an easy subject for Kinnear to handle. Soon, though, the switch to mundane everyday language hints at a virtuosity that only occasionally makes itself obvious.

When the first explosion comes nearly two thirds of the way through the unbroken drama, it has all the greater an impact. The pacing of K’s memories of youthful “crimes” – young Kinnears are similarly plastered on the walls as we enter; the shape of things to come – is well handled, too, the last two actually achieving the pathos Kafka and Gill rigorously deny us elsewhere. Quite apart from the timeliness (or timelessness) of the surveillance society reflected onstage, where Kafka’s fantasy doesn’t need much twisting, we can all imagine being in the position where, though we’ve nothing major to confess, minor misdemeanours return to haunt us.

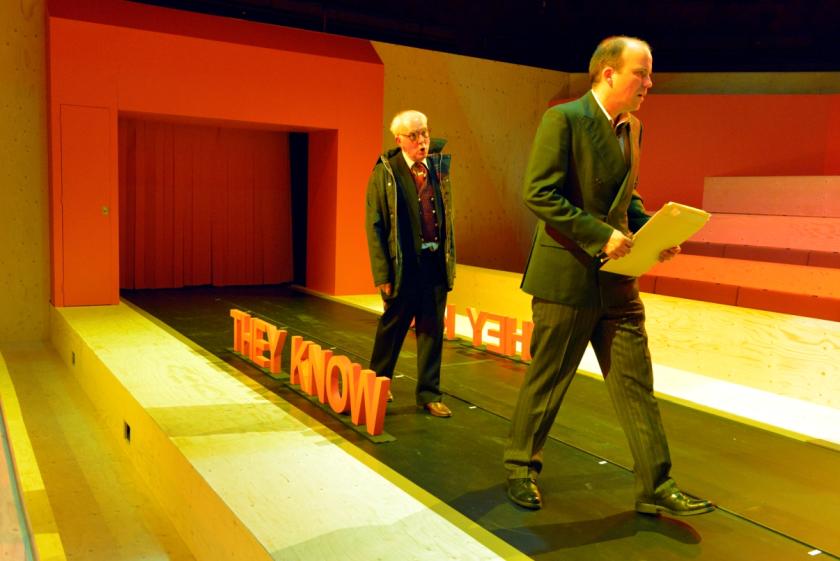

We also have to get inside Joseph K’s head, and Jones’s production manages this as uncannily as the brilliantly recessed text of the printed play (published by Oberon Books), when language ceases to resonate. As Sian Thomas’s Mrs Grace (pictured right with Hugh Skinner as barking Block), the lawyer who’s supposed to bring succour to the helpless protagonist, quickly begins to bore and befuddle us, her meaningless rigmarole has to retreat into the background while the next scene’s prepared. As often with Jones’s slow-burn production sense and his inexorable symmetries, the canine references in her furnishings and on the colour telly will make sense later, along with the ineffably timed barking offstage (even the sound effects seem part of a musical score).

We also have to get inside Joseph K’s head, and Jones’s production manages this as uncannily as the brilliantly recessed text of the printed play (published by Oberon Books), when language ceases to resonate. As Sian Thomas’s Mrs Grace (pictured right with Hugh Skinner as barking Block), the lawyer who’s supposed to bring succour to the helpless protagonist, quickly begins to bore and befuddle us, her meaningless rigmarole has to retreat into the background while the next scene’s prepared. As often with Jones’s slow-burn production sense and his inexorable symmetries, the canine references in her furnishings and on the colour telly will make sense later, along with the ineffably timed barking offstage (even the sound effects seem part of a musical score).

The only note of reassuring ordinariness other than K’s bewildered protests comes from Kate O’Flynn’s sweet-natured neighbour Rosa, but the actress also plays five other distinctly uncomfortable roles. The court room drones and supplicants are vividly characterised by a mixture of professional actors and Young Vic community actors. There are some great faces here to set alongside Richard Cant’s Male Guard and Hugh Skinner’s Block, the defendant reduced to canine dependency. What Kinnear’s K is reduced to, and how the travelator fulfils its most sinister function at the end, you’ll just have to go and see. Comfortless it may be, but such brilliantly skewed theatre is not to be missed, least of all at London's buzziest theatre.

Add comment