Those who want a taste of the way the West End used to be - that's to say, bustling star vehicles where the furniture isn't the only amply upholstered aspect of the evening - will relish When We Are Married, the 1938 J B Priestley comedy that tends to hove into view every 10 or 15 years, or thereabouts. But I wonder whether theatrical pleasure-seekers will be prepared for the tetchiness and rancour that have come to the fore of this once time-honoured comic warhorse. Indeed, take away the rather hurriedly upbeat finish and you could be mistaken for thinking that Strindberg had suddenly relocated to Yorkshire.

Consider, for instance, the fusillade of abuse that pours forth after the interval from Annie Parker (Michele Dotrice) in the direction of her self-impressed braggart of a husband, Albert (Simon Rouse). Except that Annie's catalogue of complaints is only made possible by the realisation that hers may be one of three marriages all held on the same day 25 years ago that are revealed to be possibly (and collectively) invalid - in which case, why keep up the pretence of politesse when you loathe the one you're with?

That's pretty much the sum total of Priestley's play, which takes a scalpel to posturing, whether marital or social, all the while allowing a stage full of stalwarts to grab their individual moments to shine. Past revivals have imparted a sweet nostalgia for both the period and milieu: West Riding c 1908, a community of self-made men in love with their hard-won titles surrounded by women all too ready to topple them from their vainglorious perch. Priestley even offers a comic distaff equivalent of the take-no-prisoners inspector who would come to call nine years later courtesy of this play's gossipy hired help, Mrs Northrop, whom Lynda Baron plays with a bluntness bordering on the toxic.

No doubt keen to elevate proceedings beyond a three-dimensional, sepia-tinged photo, the director, Christopher Luscombe, wastes no time puncturing the pretensions of the would-be revellers on view. Scarcely has the assemblage stumbled into view from a slap-up meal before one or another is burping or clutching a gut, casting aspersions at the chapel organist, Gerald Forbes (a nicely judged turn from Peter Sandys-Clarke), whose only crime against humanity is to hail from the "la-di-da" climes of southern England.

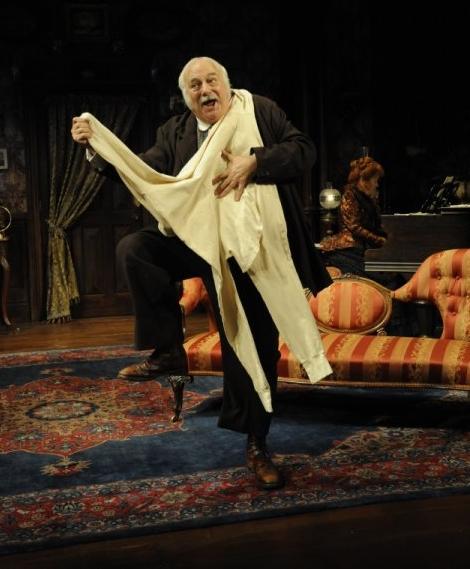

Other outsiders to events include a bibulous photographer, played with gusto (and, at one point, a pirouette) by Roy Hudd in a role I will forever associate with Bill Fraser at the old Whitehall Theatre a quarter-century or so ago. Rosemary Ashe pulls multiple faces as the cackling, squawking Lottie - perhaps the most vulgarly conceived of Priestley's chorus of disapproval. She and Hudd get a shared moment at the piano, in the process reminding us of this author's abiding affection for music hall.

The trio of silver-wedding celebrants - or not, as the case may be - is distinguished by Sam Kelly's gentle, telling "aye" at the top of the second act; Dotrice's ace timing (she reports listening to her husband for "hours" - pause - "and hours"); and Maureen Lipman playing a scold possessed of a left arm swinging ominously by her side as if ready to inflict lasting damage. In the event, no blood actually gets spilled during When We Are Married, but this is the first production of this play I've seen to suggest just how sour a sweetly regarded staple of the repertoire can in fact be.

- When We Are Married at the Garrick Theatre until 26 February 2011

- Find J B Priestley on Amazon

Add comment