Thus, for years, those comedians presenting documentaries on often immensely serious subjects of which they overwhelmingly tend to know something fairly adjacent to bugger all. Thus the - in private - no doubt perfectly mature Nick Robinson hopping about Westminster’s precincts like his own attention-seeking glove puppet at a children’s party. Thus even BBC Four, theoretically the brainiac channel, going in terror of terrifying its audience. No one wants to emit the faintest sulphurous whiff of what the apparatchiks call elitism.

The heart made its regular trip bootwards as Games Britannia, a three-part 2000-year history of gaming, opened for business last night with the standard introduction in which we were told yet again that we were to be taken on a journey. Nowadays, documentaries must be sold as some kind of package tour, as if this is the only brand of narrative an audience will buy into.

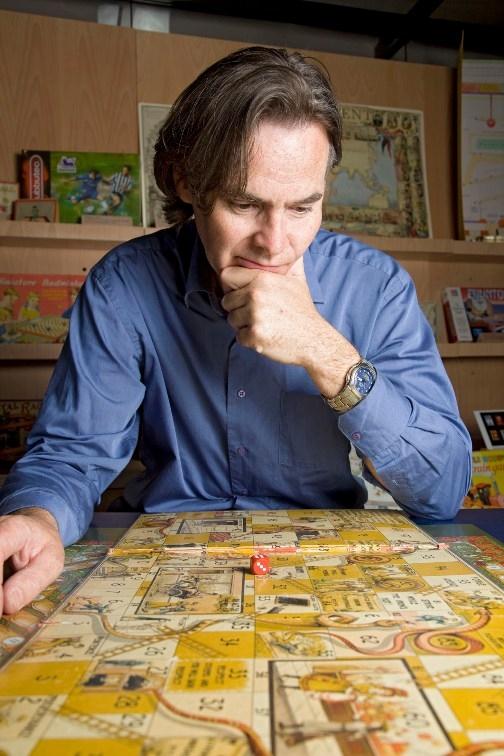

The series writer is Benjamin Woolley, an engaging figure whose dependence on a walking stick has not, mirabile dictu, disqualified him from presenting his own history. A fiver says he had his introduction more or less thrust upon him. Tell us a bit about yourself, Ben, they will have insisted. Personalise proceedings with tales of the time when playing Racing Demon your little brother called the aunt a c***. People love that stuff. Include them. “In the books that I write it’s the rich and famous who usually take centre stage,” he obediently intoned. “But there is another history. One in which we are the players.” Message: honestly, it’s worth paying attention – this one’s about you.

The truth is that Games Britannia is an academic treatise that has somehow been smuggled past the watchtowers. On the evidence of “Dicing with Destiny”, the first film, this is stealth lecturing of the highest order. It’s not entirely clear that it was about us, mind. All the games that have lasted pitched up here, in some cases circuitously, from the orient. In the Middle Ages backgammon and chess made their way towards us via the Libro de los Juegos published in 1292 for the Spanish king Alfonso X. From the colonies we got ludo and snakes and ladders, which in its Hindi incarnation symbolised a quest to move from a state of nothingness to enlightenment via the acquisition of spiritual merits. You might like to reflect on your imperfections the next time you land on that snake that slithers you from near-certain triumph down to the outer darkness of square number six.

The games we’ve invented, on the other hand, seem not to have lasted the course. With a suited Oxford don Woolley sat down to play an extremely complex game found in an illuminated Latin bible in which one player’s attempt to get his piece to one of the four corners of the board is analogous to the safe passage of a soul to heaven. For some reason that one didn't last. Nor did the extremely dull Victorian game of Goose, designed to inculcate in its young players the ways of virtue.

The conceit of Woolley’s narrative is that games offer a keyhole into the world in which they existed, which is why Victorian games were about morality and global subordination. An Iron Age board game dug up near Essex may conceivably have been used in priestly divination. The 18th-century hankering to gamble whole fortunes away at the card table found its equivalent writ large in the South Sea Bubble. And the strategic dust-up we know as chess survives because it plays out on 64 squares something that humanity has always been very keen on: war.

But sometimes, it was pointed out, games are just about fun. And Games Britannia had fun too. The academics who work in the field include the British Museum’s curator of games. The existence of that post will have taken all sorts by surprise. Its current incumbent is Irving Finkel, who looks very much as a curator of games ought, white hair sprouting voluminously every which way. With various experts Woolley sat down to play games to which no one, it seemed pretty certain, knew any of the rules. But even though they hadn’t a clue what they were doing, the loser was always grim-faced in defeat. Good game, good game.

Games Britannia continues on BBC Four on Mondays at 9pm. Watch episode one on BBC iPlayer.

Add comment