On walking into Mikalene Thomas’s exhibition at the Hayward Gallery my first reaction was “get me out of here”. To someone brought up on the paired down, less-is-more aesthetic of minimalism her giant, rhinestone-encrusted portraits are like a kick in the solar plexus – much too big and bright to stomach. Could I be expected to even consider accepting these gaudy monstrosities as art?

A brash assault on the senses, they seemed to be daring me to turn away. Then came two installations – recreations of the living room in the terraced house in Camden, New Jersey where the artist grew up in the 1970s, and the place where she spent her teens. Assembled with enormous care down to the last detail, these time capsules convey a profound sense of belonging. Although unfamiliar to me, I was able see how these lovingly recreated interiors would trigger a calming sense of déja vue in anyone brought up in similar environments. And it made me realise that, while Thomas’s world and her aesthetic are totally alien to me, that does not make them invalid.

The next road-to-Damascus epiphany was a collage whose elements could have come from Picasso, Léger or any number of 20th century masters, except that a strip of glittering rhinestones had been introduced that didn’t belong in this company – until now, that is. Thomas’s intent became clear; she is making the case for her alternative aesthetic to be accepted as part of the canon – to be embraced by the mainstream.

The next road-to-Damascus epiphany was a collage whose elements could have come from Picasso, Léger or any number of 20th century masters, except that a strip of glittering rhinestones had been introduced that didn’t belong in this company – until now, that is. Thomas’s intent became clear; she is making the case for her alternative aesthetic to be accepted as part of the canon – to be embraced by the mainstream.

The painter Noah Davis (currently showing at the Barbican) assumed his place at the table with extreme politeness and minimal disruption, but Thomas has adopted a different stratagem; she is bursting into the feast with guns blazing. And who can blame her? The artist Carrie Mae Weens, whose work first inspired Thomas to become an artist rather than a lawyer, summed up her achievement in the following words: “you talk back to the old masters, creating new ways of seeing us – seeing women.”

Portraits such a Afro Goddess Looking Forward, 2015 (main picture) give the sitter enormous dignity and poise. Worn across her face like a mask is a section cut from a photograph of her face; it allows her to return our gaze with her own eyes, as it were. Her body may be little more than an element in a complex decorative design, but her eyes remind us that she is fully present as a human being.

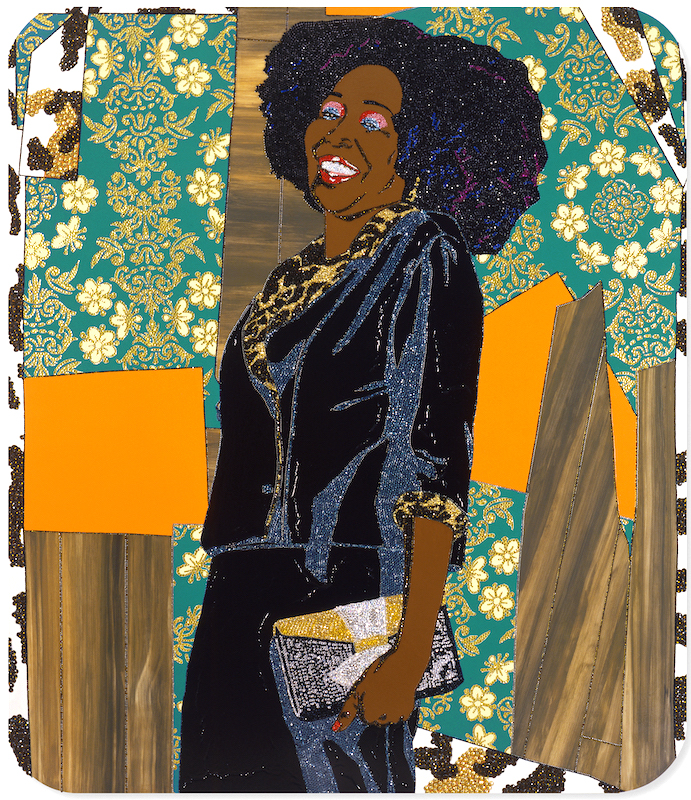

In Mama Bush (Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher, 2009 (pictured above right) Thomas pays tribute to her mother who was also an important role model. Wearing an elegant suit trimmed with leopard skin patterning, she stands tall among strips of embossed wallpaper and faux wood panelling. But the portrait has no photographic mask attached and, without it, the smiling face is reduced to an area of flat colour that even the glitter of rhinestones can’t fully animate. A Little Taste Outside of Love, 2007 (pictured above) is a riposte to Manet’s Olympia of 1863. The original painting features a black servant presenting a call girl with a bouquet of flowers presumably sent by an admirer. The white woman lies naked on a bed, like a prize exhibit on display, while the black woman merges with the shadows as though she scarcely merits a glance. Thomas redresses the balance by giving pride of place to a black woman, but this does not seem like much of a victory as the woman is still naked and on display – something for us to ogle at our pleasure. “My gaze,” says Thomas, “is the gaze of a black woman unapologetically loving other black women.” But love includes respect, while lust can be cruel and rapacious and, reclining on a patchwork of shapes whose strident patterns clamour for attention, this Little Taste looks as wary as a hunted animal.

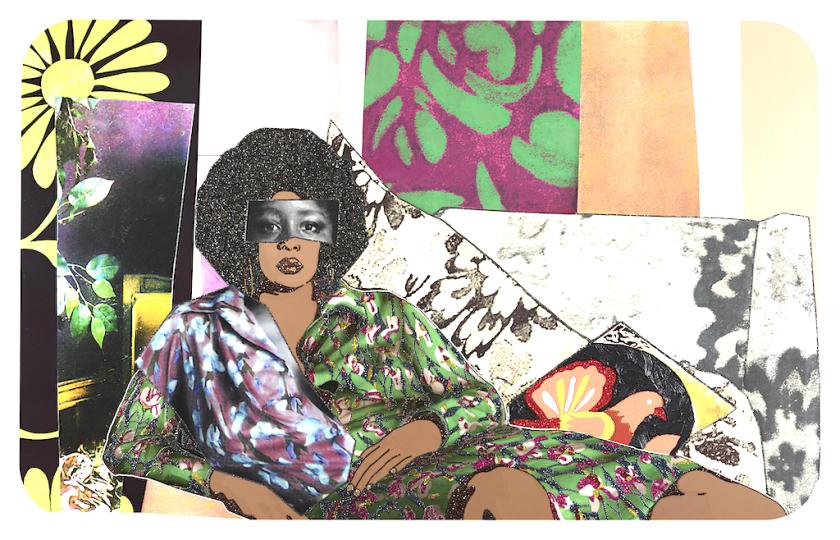

A Little Taste Outside of Love, 2007 (pictured above) is a riposte to Manet’s Olympia of 1863. The original painting features a black servant presenting a call girl with a bouquet of flowers presumably sent by an admirer. The white woman lies naked on a bed, like a prize exhibit on display, while the black woman merges with the shadows as though she scarcely merits a glance. Thomas redresses the balance by giving pride of place to a black woman, but this does not seem like much of a victory as the woman is still naked and on display – something for us to ogle at our pleasure. “My gaze,” says Thomas, “is the gaze of a black woman unapologetically loving other black women.” But love includes respect, while lust can be cruel and rapacious and, reclining on a patchwork of shapes whose strident patterns clamour for attention, this Little Taste looks as wary as a hunted animal.

The photographs which Thomas takes of her sitters in preparation for her paintings are another story. Her love and respect shines through in shots of gorgeous black women occupying the sets she creates for them with enormous confidence and grace. Beyond doubt, they prove that black is beautiful, and well worth celebrating – with or without the glitter.

- Mikalene Thomas, All About Love at the Hayward Gallery until May 5

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment